Inherent in old family photographs is its nostalgic quality, possibly produced by a combination of two things: its physical character as rendered by an analog camera or printing technique, and its function as a temporal record of what once was. Such is an object that can conjure — or even manufacture — memories, its aesthetics having the ability to transcend its historical periphery even if the viewer was not part of it.

The aesthetics of nostalgia is in critical light in Isha Naguiat’s first solo exhibition at Galerie Stephanie, Photo of a Photo. By altering her family photographs physically and chemically, the artist created more distance between her and the viewer from the original material. So then, what is left for us to grasp? What is left for us to feel?

In the first of the three-work series ‘A House in Caloocan’, the photographed porch of her mother’s childhood home invites us to enter the space. In a way, it is also an emblematic passage into the rooms of history inhabited by the artist’s family that Naguiat allowed us to peek into. In ‘A House in Caloocan’, we are granted three external views of the house. Each work consists of nine cyanotype square prints with geometrical areas filled in with short light pink embroidery. For the porch view, a rectangular space beside the left post was covered with stitches, creating a door-like frame. For the second and third views, the embroidered facade is applied to the windows.

Is the embroidery an act of highlighting, or actually hiding? While the windows are completely shut closed by the threads, the porch is still partially open to the viewer. Memories — especially materialized memories such as photographs — do not grant us a full panorama to the past, just a sliver of what we are able to remember, what remains from the things we have unconsciously blocked out.

The process of puncturing through the images can also be interpreted using the concept of punctum in Roland Barthes’ Camera Lucida (1980). In the first part of the book where he theorized about photography, he described punctum as an “element which rises from the scene, shoots out of it like an arrow, and pierces.” In the more sentimental second section, as he searches for his mother through family photographs, he comes to the realization that punctum is “no longer of form but of intensity, is Time, the lacerating emphasis of the noeme ("that-has-been"), its pure representation.”

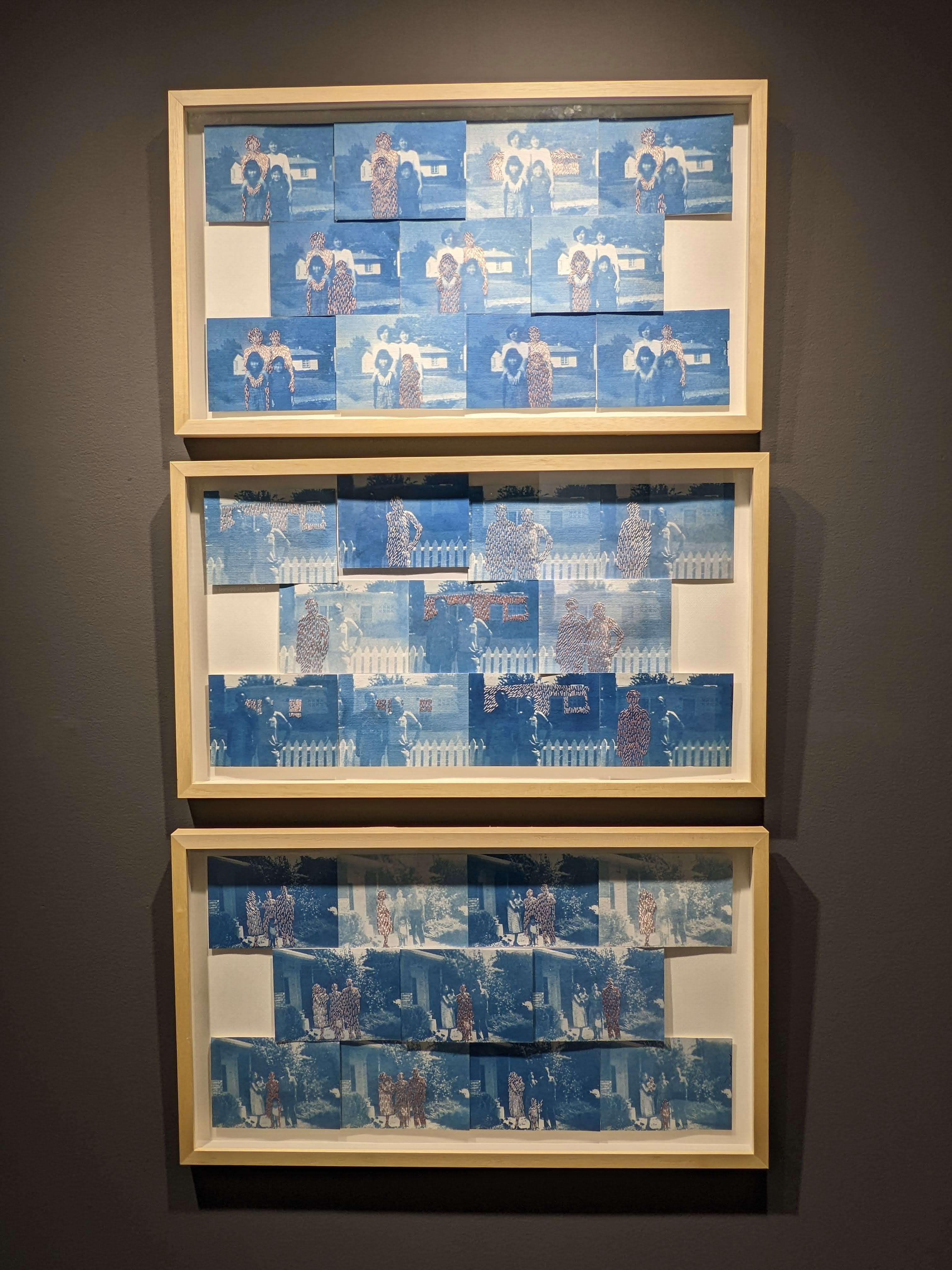

The usage of cyanotype prints and embroidery is also applied to another trio of works called ‘Memory Blocks’. ‘Memory Blocks 1’ features a family of four, while the second features two, and the third, five. Each work has one family photo reproduced into eleven cyanotype prints in three rows, four at the top and bottom and three at the middle. They are not exactly similar, as they differ in hues of Prussian blues and areas of embroidery, although there are pairs in ‘Memory Blocks 2’ that are identical in terms of the embroidered-shaded figures and houses.

The mathematics in ‘Memory Blocks’ is not only apparent in their final visual form, but also in their making as driven by the exposure time which renders the prints’ final color. Using their quantitative quality as a jumping point of inquiry, how much do we actually remember from the past? If we look into the process of making cyanotype prints, Naguiat simulates the journey of remembering: from the negative copy of a photograph subjected to procedures involving chemical solutions, ultraviolet light, water, and most importantly, time — and what comes after? A form of the original in a specific color, some details muted, some accentuated.

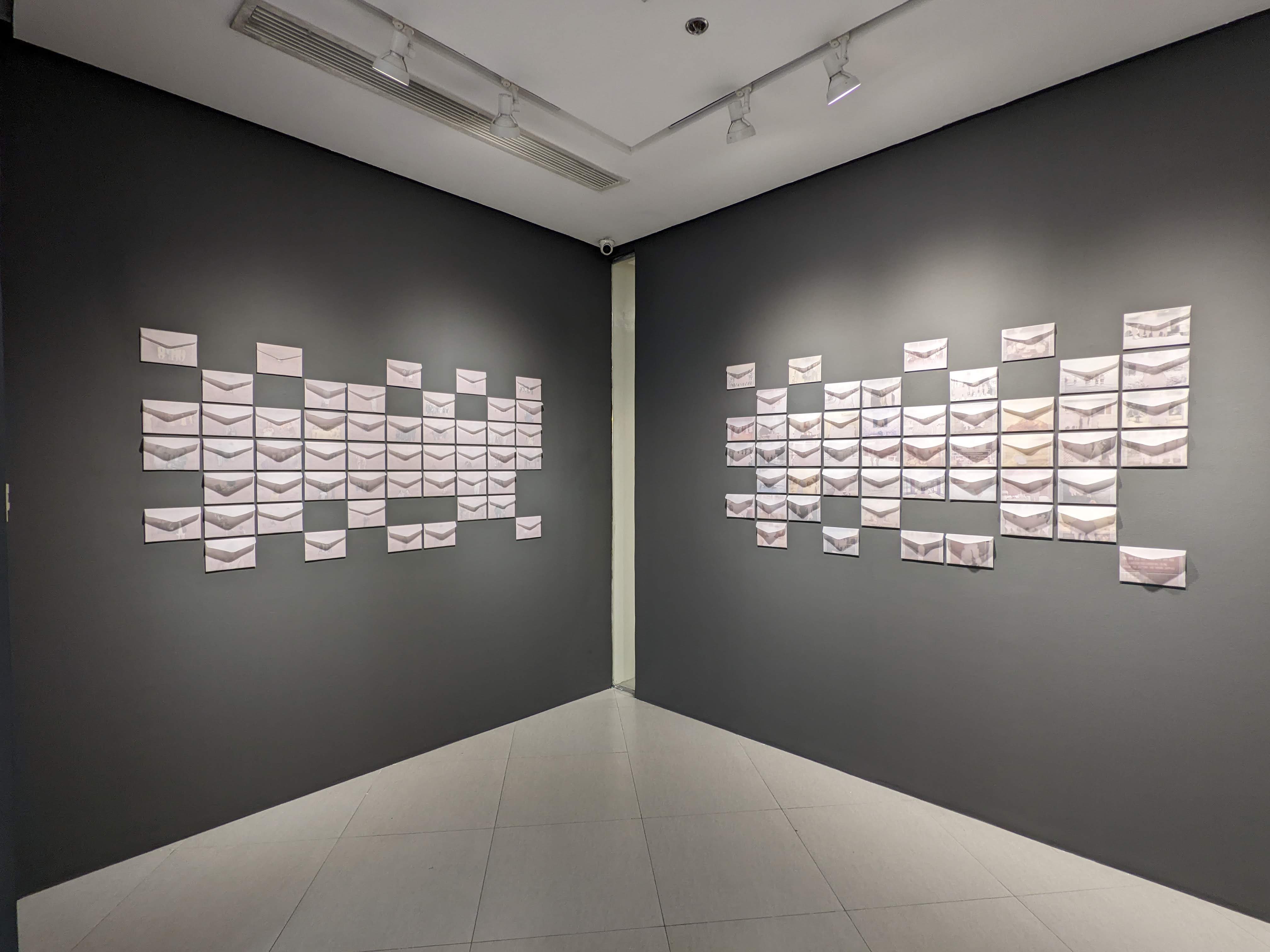

For the final stopover in the journey to memories, two adjacent walls present two interconnected works: one for ‘Subject’, and the other for ‘Context’. From afar, we can count that there are fifty envelopes attached to each wall, arranged in eight rows and ten columns. The positioning of the envelopes and the spaces within are also identical on both walls. As we get closer, we can see isolated persons on ‘Subject’ and sceneries in ‘Context’ where the people in it are incised from view. Looking even more closely, one comes to the realization that one contains the missing pieces from the other. Even after solving the puzzle, linking the subjects to their contexts only lends to more questions. Who are they? Where are they? What are they doing there? Speaking with Naguiat, she shared that most of these photographs came from her grandparents who traveled a lot, and even she doesn’t know the people in the photos. With no actual stories to anchor the photos, we are left to create our own as we look into the people and backdrops, barely identifiable in the first place through the translucent envelopes.

Speaking of the enclosures, the envelopes also symbolize the idea of a message: To whom will they be sent? From whom did they come from? Envelopes as containers of messages (like photographs are containers of memories) also symbolize a relic of the past — another form of nostalgia.

In the end, what do we make of the nostalgia in these old photographs and envelopes? Perhaps, we can turn back to Roland Barthes who, in the final line of Camera Lucida, suggested the following when looking into photographs: “to subject its spectacle to the civilized code of perfect illusions, or to confront in it the wakening of intractable reality.”

Photo of a Photo continues at Galerie Stephanie until September 29.

Lk Rigor is currently pursuing MA Art Studies in UP Diliman. Aside from being a curator, she dreams of becoming a cat lady someday.

Images courtesy of the writer.