In the late eighties, two siblings laid the groundwork for what would become a critical work of Martial Law literature. Susan Quimpo had been taking journalism classes at Ohio University. There she wrote about her family’s participation in the revolutionary movement against the Marcos dictatorship. For her submissions to workshops, Susan penned autobiographical stories about separation, survival, and resistance in an effort to compile her family’s Martial Law experiences. One day these essays could make a book, Susan thought.

However, by 1991, she began hearing rumors about the internal conflict and violence of the revolutionary movement, of comrades in Mindanao killing one another, of concealed mass graves, of the bitter rivalries between leaders. Shocked at the cruelty of those whom she thought were on the side of justice, Susan became uneasy continuing work on the manuscript and eventually decided to scrap it.

Meanwhile, while the revolutionary movement was in free fall, Nathan Quimpo found himself in political asylum in the Netherlands. Returning to the academe, Nathan had been completing his master’s degree in international relations when the idea to narrate what went wrong in the revolution sparked in his mind. Poring over the files of comrades across the globe, including his brother Ryan, Nathan set himself the task of writing a historical memoir about his experience in the revolutionary movement. This turned out to be a thankless task. Scholar that he was, Nathan felt he lacked the narrative skills to finish his memoir and found what he wrote devoid of energy, verve. Like Susan, he put aside his work and focused on teaching.

Twenty years later, Susan and Nathan published the family memoir Subversive Lives with the help of their friend,historian Vicente Rafael. It was Rafael who suggested to Susan, in a conversation in 2005, that the two siblings put together their writings and, not only that, to invite the rest of their surviving siblings to contribute chapters of their own. The product of this collaboration, with editorial duties helmed by Susan and Nathan, is a wide-spanning archive of the Martial Law years. Traversing experiences of youth activism, torture, undercover schemes as well as family photographs, songs, and poems, the narratives which comprise Subversive Lives assert the importance of remembering as both a political and social response.

What are the stakes of remembering? The results of the May 2022 elections prove that memory is in many ways malleable and unstable, able to succumb to the wildest of fictions depending on the shape and tellers of the narrative. Subversive Lives, encountered today, is a counterpoint to the memory manipulation at play in contemporary politics. “Our family’s history is just one of many families that suffered in the course of the struggle against the dictatorship,” Nathan and Susan wrote in the preface. “At the Bantayog ng mga Bayani, we have scrutinized the names in the displays and on the Wall of Remembrance…What little we know of their stories… the names of young heroes and martyrs who were among the best and truest of their generation.”

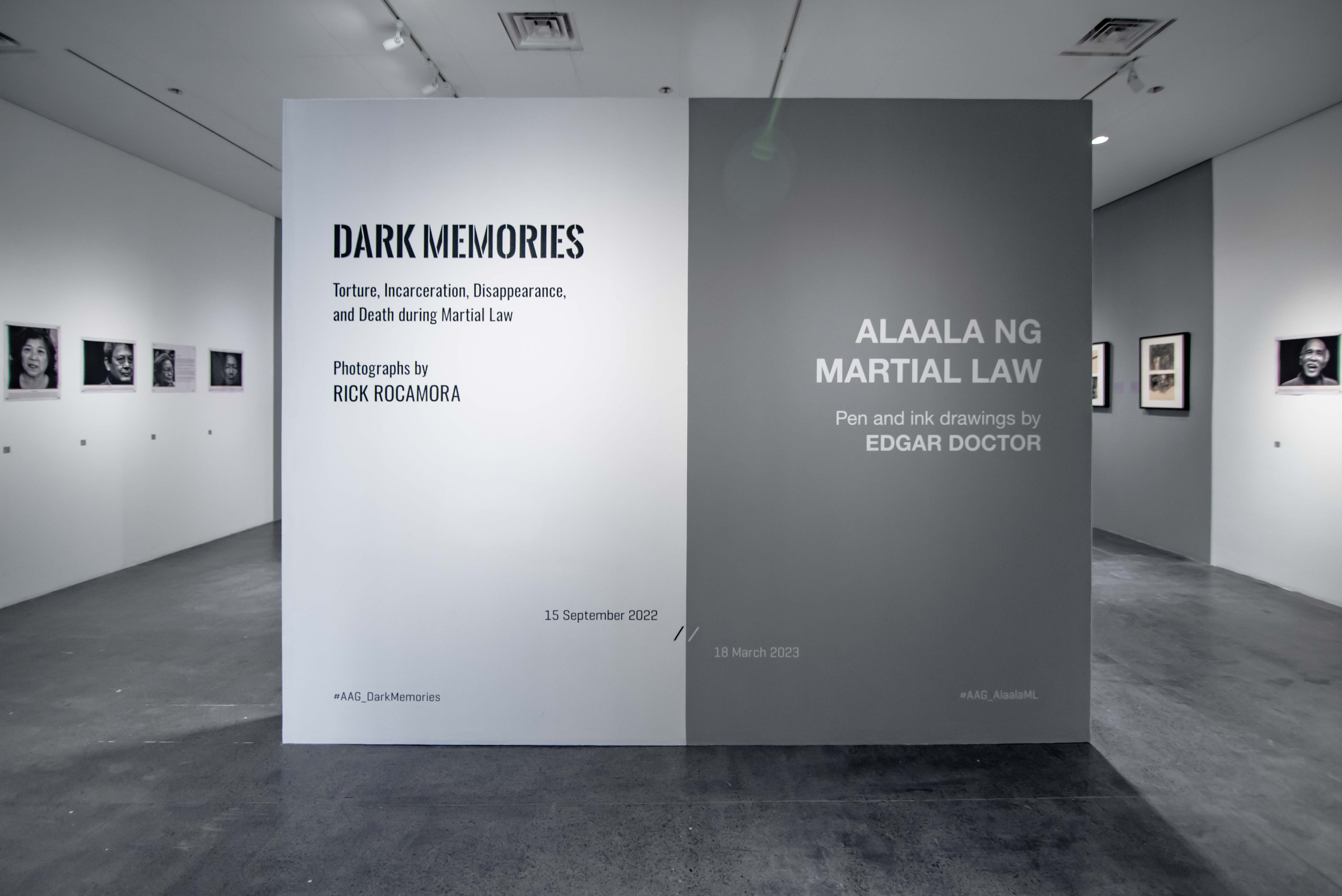

Let us now add the tandem exhibitions Dark Memories: Torture, Incarceration, Disappearance, and Death During Martial Law by Rick Rocamora and Alaala ng Martial Law by Edgar Doctor, both on view at the Ateneo Art Gallery, to this growing body of testimony on the atrocities of the Marcos dictatorship. Part of the Ateneo de Manila University’s Martial Law @ 50 effort, these are two additions which look with vital clarity at the stakes of memory. The operative word here is look. In these works, looking is no ambiguous act. To look — clearly and intentionally — lands as a corrective against the erasure, silence, distortion of memory.

The two exhibitions pursue looking through different means. In Rocamora’s artist statement, he explains the genesis of Dark Memories, which dates back to the 2011 awarding of claims to victims of Martial Law at the Commission of Human Rights. “I made a personal promise,” Rocamora wrote, “that the focus of my work in the Philippines shall be its political, social, and economic life, particularly on concerns on human rights violations.” A photographer whose work mainly involved capturing the life of Filipino war veterans in the United States as well as of his travels across South America and Africa, Rocamora sought to reorient his work back to his homeland.

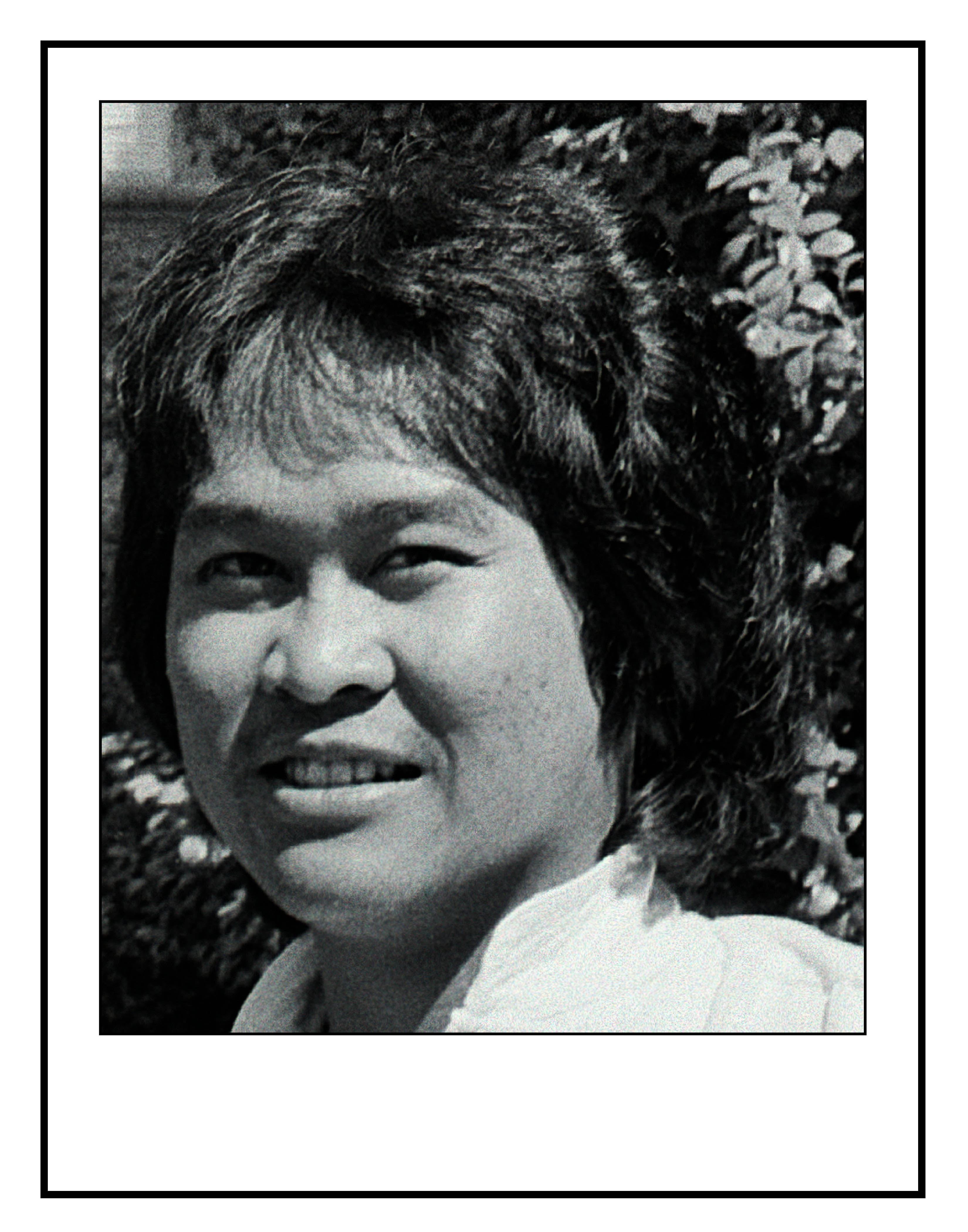

Dark Memories is a series of portraits of Martial Law victims and survivors, as well as of their friends and family who live to tell their stories. Accompanying each photograph is an account of the subject’s experience of Martial Law atrocities. In one entry, the journalist Pete Lacaba describes the torture method known as the San Juanico Bridge: “I was made to lie down with the back of my head resting on the edge of one steel cot, both my feet resting on the edge of another cot, my arms straight at my sides, and my stiffened body hanging in midair.”

Other accounts, such as Isagani Serrano’s, emerge in the form of poetry. Titled “My Children They Are Dreamers,” Serrano’s poem depicts a speaker pondering on his children’s inheritance, hoping for a life of simplicity and quiet dignity in contrast to the Marcoses’ extravagance and wealth. “My children will not go rich / They will not be like Imee or Borgie But they will be as rich / In their dreams and fantasies,” the political prisoner wrote.

All throughout Dark Memories, Rocamora trains his eye on the inherent dignity of his subjects. A few sport smiles accompanied by a wearied expression, but most of the time, eyes wide open, these faces dare us to sit with their pain.

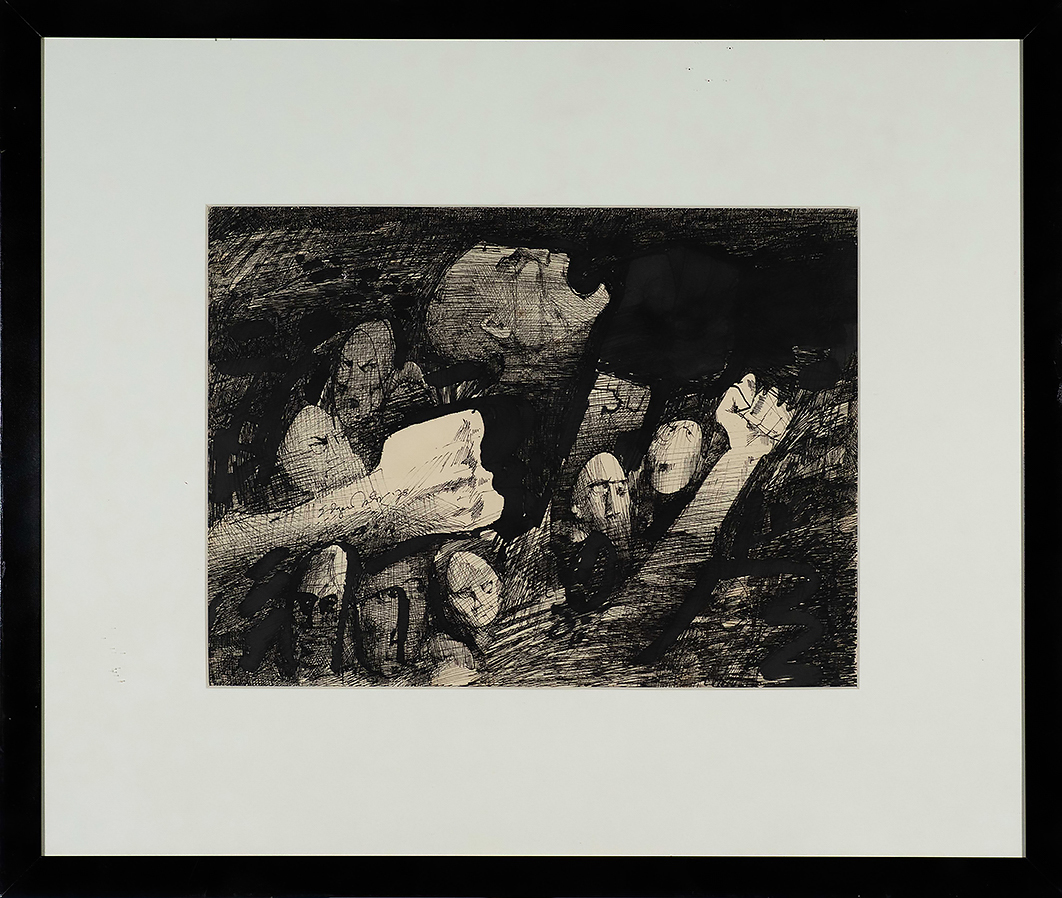

Where Rocamora’s Dark Memories is suffused with the knowledge of hindsight, Doctor’s Alaala ng Martial Law can be read as snapshots of turbulence in real time. The pen-and-ink drawings which make up Alaala ng Martial Law do not reference explicit incidents during the Marcos dictatorship but instead register scenes of disquiet and corruption; collective trauma the spectral force looming over each fine line.

Better known for his lush and abstract watercolor paintings, Doctor’s bare bones approach in Alaala ng Martial Law draws attention to the urgent need to catalog one’s emotional reality during a moment of crisis. Doctor transposes this reality through shadow and slippage, allowing the light to leak only occasionally. In the series “Alingawngaw ng Pagtutol,” faces and hands emerge as reprieves from the void, remnants of humanity otherwise swallowed up by the bleak force of death.

That interplay, between human dignity and the Marcos administration’s disregard for it, is echoed in many of the drawings, though a few other works shed just as much light into actors of injustice such as in “Kronis” wherein smug mercenaries take up space with armed police. Or in “Emperor’s Men,” which depicts figures fragmented by the darkness of Doctor’s ink marks. Faces unsettle, streaked by slashes of black like fault lines about to crack at any moment.

“Ang mga iginuhit na ito ay batay lamang sa aking nasaksihan, narinig, at naramdaman sa pulso ng publiko noong panahon ng Martial Law” (“These drawings are based only on what I have witnessed, heard, and felt from the pulse of the public during the time of Martial Law”), Doctor explains in a note featured in the exhibit. Beginning the series in 1971, Doctor’s Alaala ng Martial Law are memories performed and activated not in a vacuum, but through the tempo of a community.

“Performing memory can thus be understood as an act of memorialisation,” writes Liedeke Plate and Anneke Smelik in the preface to their volume Performing Memory in Art and Popular Culture. For Plate and Smelik, memorializing something helps us understand memory as a phenomenon that is dynamic and processual, and in turn emphasizes memory’s capacity to rouse the “active agency of individuals and publics.”

Both Dark Memories and Alaala ng Martial Law memorialize the loss and violence of the Martial Law years in ways that spotlight the link between memory’s public and private lives. That uneasy entanglement which has the potential to mobilize our own sense of agency. Caught in the half-light of these works, I think of the doubts faced by the Quimpos as they embarked on the difficult work of memorializing their experience. “Not everyone found it easy, or desirable to revisit the past,” Nathan and Susan wrote. The labor of memory, to sustain and cultivate it, lingers in these works as they arrive in our shared present.

Dark Memories: Torture, Incarceration, Disappearance, and Death During Martial Law and Alaala ng Martial Law will be on view at the Wilson L. Sy Prints and Drawings Gallery, 2/F Ateneo Art Gallery, Soledad V Pangilinan Wing, Areté, Ateneo de Manila University until 18 March 2023.

Sean Carballo is a writer and undergraduate from the Ateneo de Manila University.

Images courtesy of Clevfan Pornela and Ateneo Art Gallery.