Last November 25, Gravity Art Space (GAS) gallery opened the second run of The No Name Show (“The Show”), its first edition occurring in late 2021.

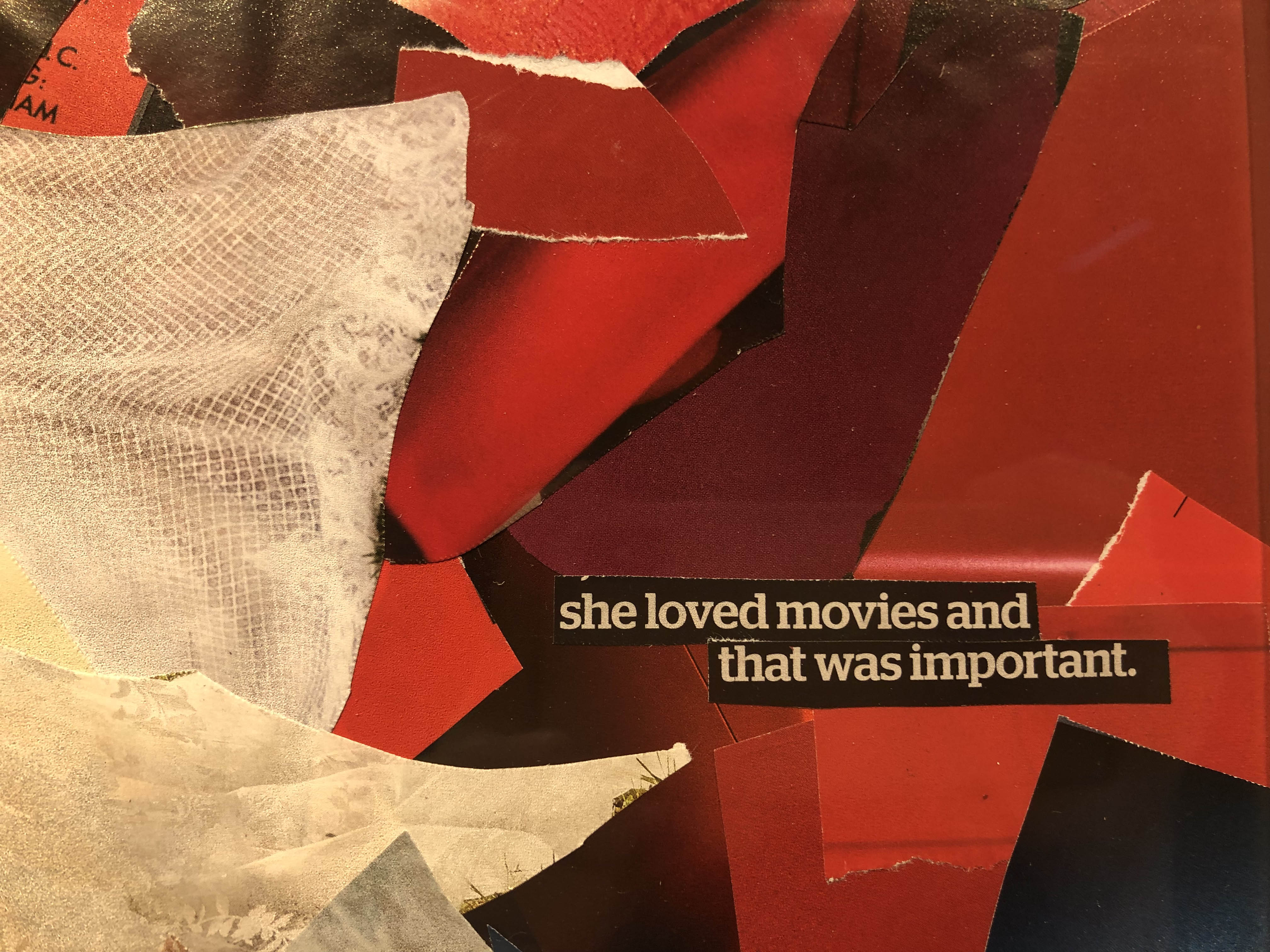

More than 120 artists sent works in mediums ranging from installation, painting, sculpture, textile, and multimedia to GAS for The Show. No names were displayed next to the works in the gallery, though the names of all artists, in alphabetical order (albeit based on first, not last name) greet audiences at the exhibit entrance.

Already a daring move at the height of the pandemic, The Show’s continuation as pandemic restrictions relax highlights not just the urgency of its message nor the relevance of its ethos, but more importantly how it connects to both audiences and most especially to artists, even beyond those participating.

The participating artists consisted of both veteran and up-and-coming artists. Now, many exhibitions often feature these two groups side-by-side, but having no names next to the works displayed blurs the line between “established” and “emerging” and shifts the focus away from “brand” to what could be a purer form of aesthetic enjoyment.

Nonetheless, during The Show’s duration, GAS offered a guess-the-artist game that visitors could play.

Level the field

“It’s a big deal to be considered a big name in the art industry,” says Tato Yap, a participating artist and undergraduate sophomore from the UP College of Fine Arts. “By not having a name,” he expounds, “it allows your work to reach people especially as there are big names with us.”

For GAS co-founder and practicing artist Indy Paredes, the “no name” program also affects art audiences and collectors: “Andami kaseng mga collectors na they acquire by name. Once na pinost namin ang poster, ta’s merong pangalan na gan’to, they will ask, ‘uy, nasaan ang work ni ganito?’ Without even seeing it.” (“Many collectors acquire based on name, once our show poster goes up, people inquire about certain artists’ works without even having seen the show or the works.”)

Another young artist exhibiting their works, Alexandra Monserrat (who happens to be in the same year and block as Yap) feels the same way, noting how “feeling ko nawawalan ng sense ‘yung artwork kase titingnan mo muna ‘yung label before the art” (“I feel like the artwork loses its sense as people look at the label before the actual art.”)

Meanwhile, long-time artist, music producer, and wearer of many hats, Romeo Lee believes that shows like these are important inasmuch they give creative and decision-making power back to artists.

“Kailangan ma-educate ang mga collector (“Collectors need to be educated”),” he laments, noting how “trends” in the art market force artists to paint what sells over what they want to paint. Lee shares that to pay the bills, he paints what’s popular.

Between knowing laughter, Yap and Monserrat echo this sentiment, enumerating what’s marketable: “bright colors, mother-and-child, romanticizing the province.”

My conversation with Lee happens in the GAS back office, where his older paintings are displayed, paintings he’s known for: Comical scenes of Filipino life, albeit somewhat macabre, somewhat dark, think of a surreal counterpart to Larry Alcala.

“Guess which painting is mine in the show,” Lee winks, gesturing at the old works, “it’s not like any of these.”

Despite that, the show was funded in large part by GAS’s investors and regular patrons. So rather than an opposition between artists and buyers, Paredes believes that GAS and The Show’s mission is to hold space for conversations to deepen art appreciation, in the process, allowing painters to paint what they really want rather than what sells.

Taste: Gatekeeping vs. cultivating

Paredes gets excited as he talks about the whys of The No Name Show, from languid English, his voice modulates as he switches to Taglish: “Hindi mo naman ma-co-cover ang art history. Pero ang art appreciation, in one snap, pwede mong mapa-appreciate ng iba pang level ang isang tao basta kausapin mo siya.”

(“You can’t cover art history in one go, but art appreciation, in one snap, you can help a person appreciate a work in ways they didn’t before, as long as genuine dialogue occurs.”)

For Paredes and The Show’s organizers, audiences aren’t the enemy, and aesthetic appreciation can mature without an artist – or a gallery – being pedantic.

First-timers at galleries and to art, in general, are often intimidated by art spaces, art practitioners, and those more knowledgeable in art. This is in part due to the shifts in how galleries began marketing themselves as exclusive, elite spaces in the 20th century, according to the Freakonomics Radio podcast.

While the above highlights a Western context, the same could be said in the Philippines, as it has been seen as a pastime of the “alta ciudad.”

With the advent of new tech and approaches to presenting works, art has recently become more mainstream and “Instagrammable” thanks to bigger, more inclusive art fairs and markets as well as galleries and digests investing more in digital spaces.

Paredes notes how many visitors to GAS are usually there “for the grid and ‘gram,” posing with works, sometimes even doing TikTok dances in front of them. But rather than be flustered, he and his team try to help visitors unearth what he believes is everyone’s inherent ability to appreciate art on different levels.

While the art world has steadily become more accessible, this development also poses the challenge of being forced to create the same things according to the same styles over and over again as revealed by veterans and young artists alike such as Lee, Yap, and Monserrat.

Can creativity surmount market forces?

For Paredes, the way forward is first through creating a non-intimidating space and, having done that, allowing art makers to engage in good faith with their audiences: “Community is what helps us, so we have to help the community.”

Check out the exhibit at Gravity Art Space, Mother Ignacia Avenue, Quezon City, until December 23.

When Pao isn't writing about art, he's trying to be a cat-whisperer.

Images courtesy of the writer.