Waiting: that stranded, confused state of anticipation. Neither an entirely passive or active predicament, but potent. It usually arrives accompanied with the strong sense that time is being lost. The realization that while waiting, my time is being spent. Waiting’s ubiquity can be traced back to nearly all aspects of modern life: from traffic and the pitfalls of public transportation to the interior tug of capitalism. Over the daily course of living, it seems we’re always waiting—waiting for something better to come and sweep us off our feet, waiting for some undefinable change, waiting for life to happen to us.

Nevertheless, there’s a romantic tinge to the practice of waiting, an ache that renders us momentarily porous, submersible. The French literary theorist Roland Barthes knew a thing or two about waiting and its peculiar weight. “The lover’s fatal identity is precisely: I am the one who waits,” Barthes wrote in A Lover’s Discourse. In that work, a loose, fragmentary collection dissecting a lover’s identity, Barthes dedicates a section to waiting. For Barthes, it is both a “tumult of anxiety” and an “enchantment”—two terms that function as similarly apt descriptors for the art of Allan Balisi. With Among the good wishes, his latest solo exhibition at Silverlens Gallery, he strikes upon the white hot anticipatory energy of waiting, channeling scenes that teeter on the edge between enchantment and anxiety.

Across the paintings of Among the good wishes, figures and tableaux linger in washed-out frames of overexposure. Vicious fires drown out the scenery in “A Single Chorus, a Single Murmur,” a canvas depicting an intense moment of ongoing destruction filled with a scatter of harsh reds and turbulent whites. As viewers, we are positioned in a tragic moment just as it happens as though we ourselves are waiting for the event to pass, waiting for another witness to arrive. The scene is sobering, entrancing, and full of vivid emotional resonance.

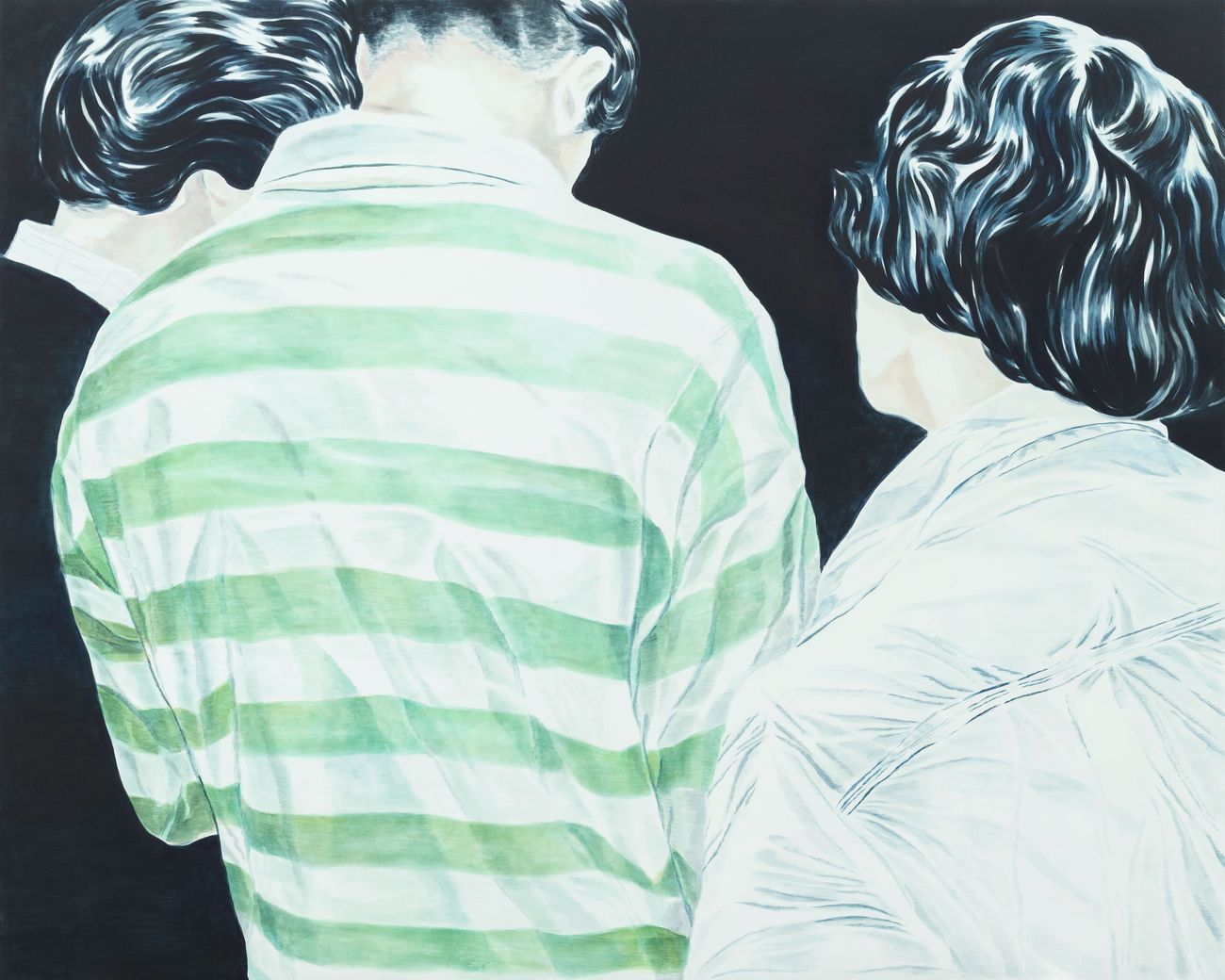

Balisi revels in these momentary dramas. In doing so, he forges a path beyond the stagnancies of individual identity, creating a world that prioritizes the swelter and air of emotion. “I like the idea of anonymity in human figures,” he once said in an interview. Anonymity, Balisi remarked, can give way to its own identity, one decentered from the expressions of the face. In Among the good wishes, faces are obscured to allow other possibilities in deciphering emotion, such as body language, perspective, imagery, and color. The dancers in “Please send applause and some good advice,” for instance, are caught in a tensile, angular pose: the severity of their stance evades a straightforward reading, whether the pose is accidental or choreographed, but the awkward focal point of the painting, and the throbbing red hues which accompany it, disturb any stability we may arrive at.

But more than just being a way to challenge his viewers, Balisi’s rendering of anonymity also gives way to a distinct and fraught experience of time. The faceless, capped figure of “Moving,” awaits a taxi cab in a kind of cinematic splendor that recalls a photo-negative variant of the Wong Kar-Wai aesthetic. The painting’s bittersweet yet tasteful blurring draws us into this character’s inner drama while shuttling us forward along with the taxi’s motion, the perspective playfully askew.

This flirtation with time’s passing is rendered especially explicit in a series of paintings that depict various clock faces stopped at differing times. Each painting comes accompanied by an image of a plain white cloth descending upon a flagpole as the series progresses. It’s an apt pairing that reveals two ways time can be measured, underscoring time’s artificiality within the modern landscape. Seeing these paintings closely, just like Barthes’s lover, we wait anxious yet enthralled by the eerie, discontinuous trickle of time.

In one striking observation in A Lover’s Discourse, Barthes describes how “everything around my waiting is stricken with unreality.” Taking in Balisi’s strange and stilted world, we are positioned at similarly defamiliarized angles, slipping in and out of poignant moments, all of which Balisi orchestrates with a sly, suggestive hand. “Revolution off Everyday Life” shows a man obscuring his figure with a white cloth, possibly the same cloth being lowered on a flagpole in the aforementioned series. The significance of the white cloth continues to be slippery, but it does reveal a preoccupation—as seen in the rest of Balisi’s art—for reworking imagery and in turn, undoing and remaking identities in the process. In the expanse of Balisi’s latest show, the actual meaning of his art may be hard to track but the feelings they evoke remain fluorescent.