You could say that I have been following Maricar Tolentino’s work since the first time I saw one of her pieces at a show in late 2022. It was part of a group exhibit curated by Empty Scholar called A Play Without An Audience at Léon Gallery. Her only piece titled 'Buy One, Take One' was an image of a woman cut into two parts.

In this piece, Tolentino fashioned a woman’s image entirely out of thread on fabric. She constructed the left piece to reveal the woman’s cleavage and the swell of her breasts; the expression on her face was solemn, partially obscured by shadow, and her right eye was stitched almost wholly black. There were specks of loose thread all over her face—white, red, green, red, brown—stitches that folded hungrily over themselves, over and over.

On the right, I saw only her calves, right down to her toes. It was constructed so that as onlookers we were not oriented in the third person but positioned from above so that it was from the perspective of looking down at her own body, seeing what she sees. I didn’t realize this at that time. I wondered about the woman — was she a victim of gender violence or sex trafficking? Was it a self-portrait?

Tolentino used brown and black tones to hem the woman’s image together. But the background was made of red thread so that the woman seemed suspended in a red chasm, removed from time and place. The piece was a self-portrait, I would later discover. Tolentino's statement on the Empty Scholar page said, “I begin with capturing my likeness, a practice that alludes to self-mastery that engages in a process of meditation with material, subject, and social environment.”

I was alone inside the gallery that Saturday morning; I could almost hear the piece pulsing in the silence like the soft echo of a waterfall’s crash, a distant swarm of wasps. I haven’t forgotten it since.

In March, I went to “Woman: Thesis and Antithesis” at the Yuchengco Museum in Makati, showcasing selected pieces from the Cultural Center of the Philippines’ 21AM Collection. I learned during the walk-through that of the seventeen Filipino visual artists who were named and conferred the national artist awards, none were women.

“Who defines women’s image? In yesteryears, it was tradition, and often a male-dominated perspective rooted in the flesh, or a form forced to be subjugated. And women followed,” the notes distributed by the museum read. Paintings of women by male artists like Napoleon Abueva, Benedicto “BenCab” Cabrera, and Fernando Amorsolo were featured alongside acclaimed women artists like Paz Abad Santos, Pacita Abad, and Anita Magsaysay-Ho. The exhibit aimed to juxtapose the idealized image of woman with women expressionists who militantly advocate for shifts and changes in their roles as women and how they are perceived.

Women have been portrayed in contrasting ways—goddess, mother, victim, heroine, martyr, whore, seductress, and real person. And since the time women have expressed themselves creatively, they’ve carried the weight of tradition, authority, and power imposed by men, society, and even themselves in their own art-making.

The question of women’s representation in art has always been contested; many signposts in film, literature, and visual arts in Western history and even our own have sought to properly articulate this dissonance. While I don’t intend to dissect this thesis any further than it has been exhaustively explored already, this was where my head was when I stepped inside Art Verité Gallery to see Tolentino’s new exhibit, Sipat, her maiden solo show.

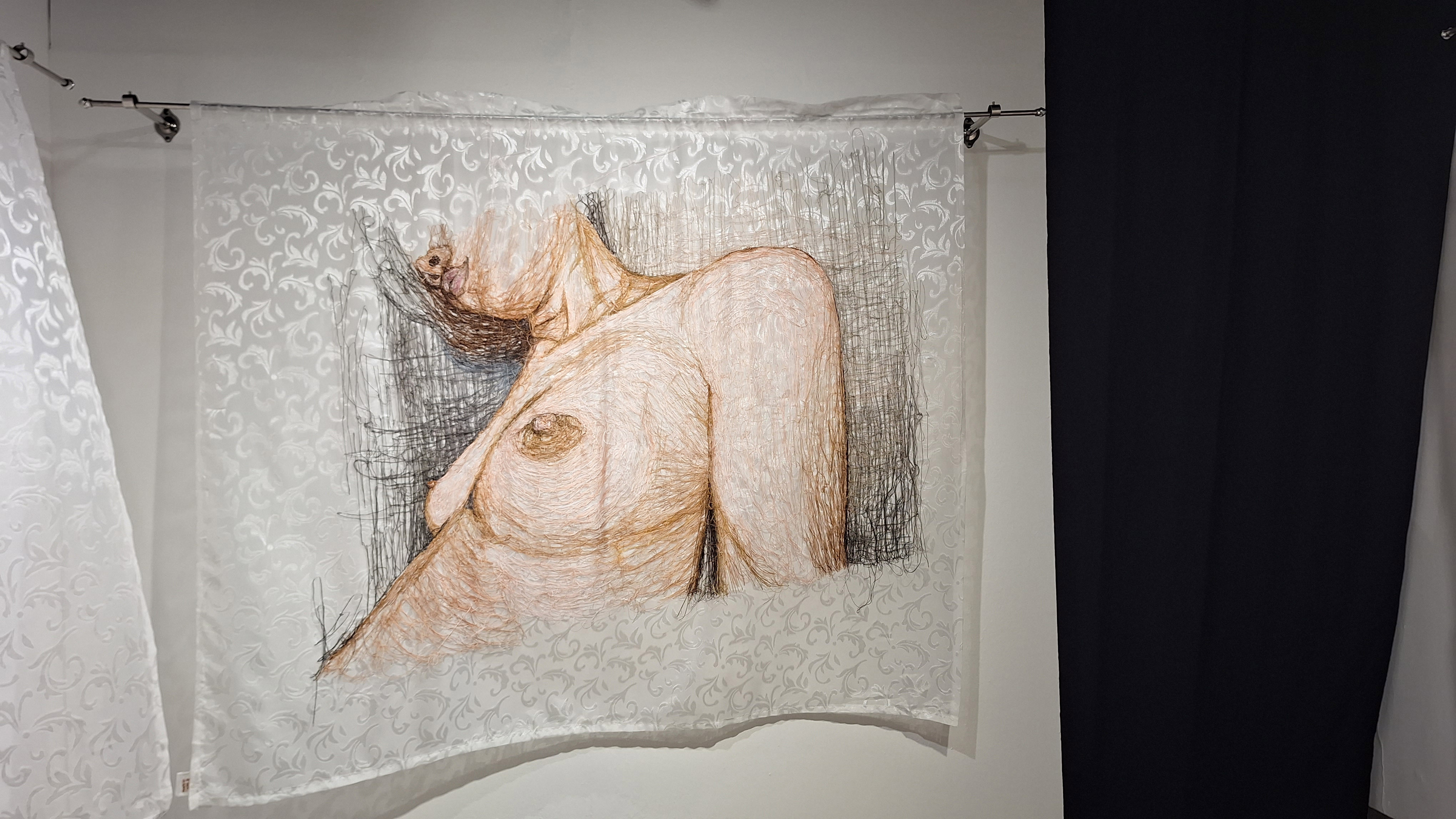

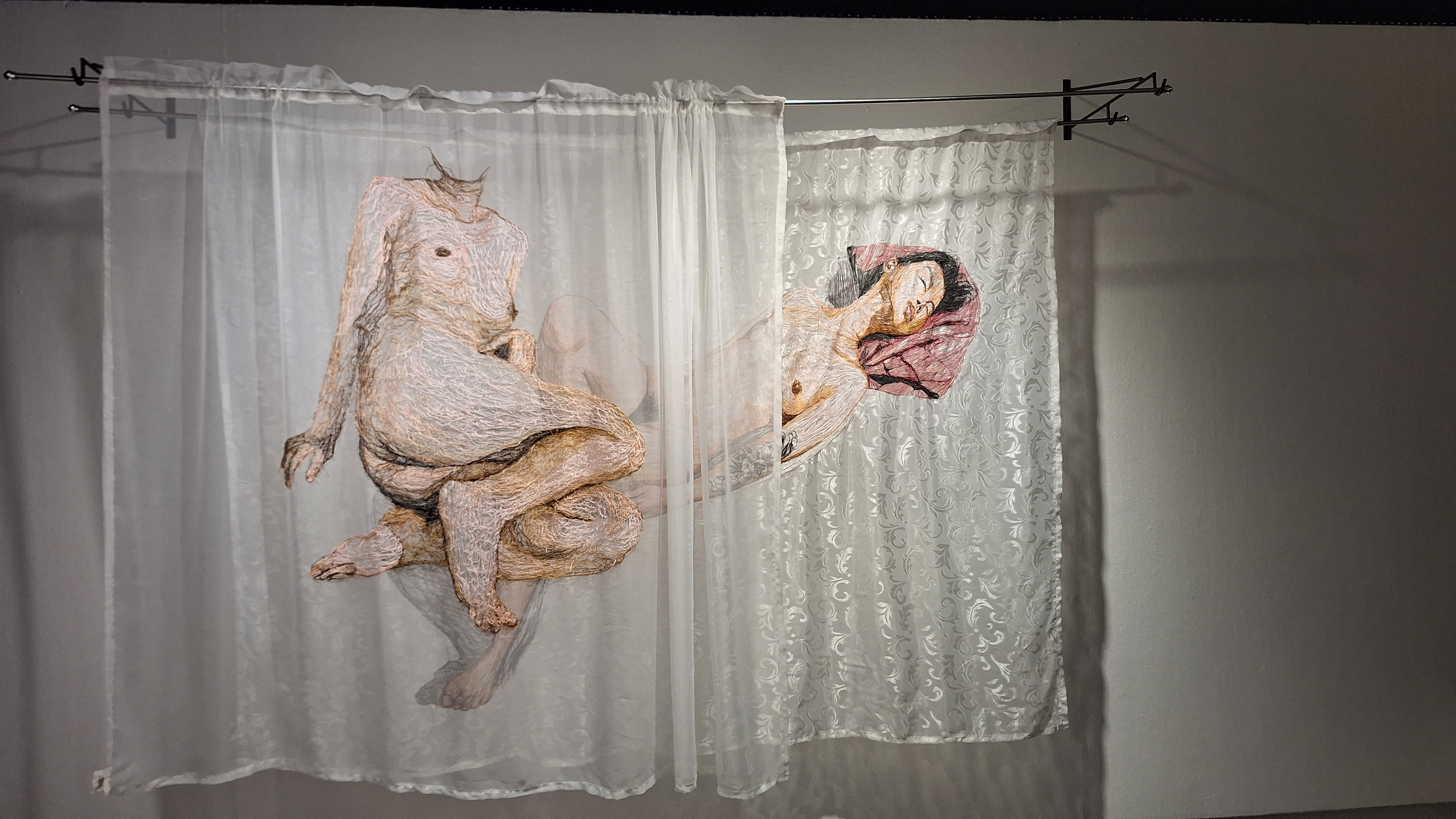

The gallery is a small one; it is, in fact, a nondescript space alongside an antique store and nail salon, away from the flurry of sight-seeing families, nervous dogs and their petulant owners who come and go downstairs. The space was blanketed in all three corners with Tolentino’s work, two of which on the right hung high from metal rods like curtains. The show itself aims to be a commentary on the way that the internet has exacerbated bodily fixation and fetishization by the ease with which we obtain leaked sex scandals, nudes, and all the varieties of porn known to man—the subject of which, unsurprisingly, is the woman, a sexualized being, clicked, liked, shared, zoomed in and out ad infinitum by the enthralled spectator.

The exhibit notes describe her work and process as “brazen”, “masochistic", “[plunging] the viewer into a frenetic hallucination, the energetic stitches obliterating any semblance of flesh into a deconstructed mass and textile”. All these seem to be evident in the “swathes” of thread that construct the female image in 'mula ulo hanggang paa' and 'an arm and a leg', her biggest works in the exhibit, and her most voyeuristic. If you step back, you see the image for what it is, “an unclothed woman in repose.” It is an image that traces its origins back to the reclining female nude since the Renaissance— one of the central images in Western painting—and further solidifies the tyranny of the male gaze than perhaps any other artistic stereotype.

The woman in Tolentino’s work is reminiscent of famous paintings such as Giorgione’s 'Venus Resting' (c. 1508-10) and Diego Velasquez’s 'The Rokeby Venus' (c. 1648-51), credited for popularizing the image. But she undermines this tradition with her own interventions: her sheer, jacquard fabric canvases thrash quietly in the gallery's air conditioner breeze, taunting the onlooker to touch them almost. But their diaphanous allure is also their neatest hoax. Tolentino’s threads, a cultural object of domestic dependability, become more pronounced upon closer look, her finishes less consummate, and the woman vanishes, disintegrating into layers of string. The subject becomes illusion. Was she ever really there?

One cannot look at Tolentino’s work without considering the way that women’s bodies have served as a narrative and frame for contentious politics. And yet, I couldn’t help but think of her work not just as social critique insomuch as a way of looking. By being the artist who holds the needle and the one being rendered on fabric, she creates a new representational configuration that disrupts the precepts of the male gaze and expands the realms of her subjectivity.

She does this more perceptibly in “gallery,” a tapestry of earthy mauves, olives, and terracotta, a departure from her previous works in thread color. It’s a reference to our actual phone galleries, where fleeting, often trivial, snapshots of our lives are stored, hoarded, and uploaded anytime to cloud servers. The tapestry is an album of nudes, and just like “Buy One, Get One,” the model’s poses and the angles suggest they were taken by the model herself. Several images show her lean stomach down to her crotch, while others capture the model from a wider angle in languorous poses. By turning the lens to herself, she performs, both for the camera and behind it.

For many women, our photo galleries are tea leaves that configure the past, present, and future but they are also repositories of our own desires. Perhaps no longer the desire to just be desired, but the aspiration to look at oneself lovingly, or at least with less scrutiny. Tolentino herself admits that her works emerge from a place of hatred and spite for her own body, and when she engages in the process of art-making, centuries of patriarchal conditioning about oneself become increasingly moot.

Confronted with her body-made-image, she herself as artist now has space for making new meanings, and what emerges from her own work expands the definitions of what her body represents and constitutes.

Is Tolentino saying that by observing her body first, paying acute attention to how her body exists in the world culturally, socially, politically, and historically, she brings about change in that body? More than her brazenness as thesis, as an argument, hers becomes an act of creation.

Perhaps self-construction begins when there exists a fracture in the illusion; when art no longer acts as enchantment. Instead, it’s the precise moment we witness her, the woman, gazing at herself, as muse, as model, as artist.

Sipat is on view at Art Verité Gallery in Taguig City until October 19.

Zea Asis is a writer from Manila.