The topography of girlhood is a treacherous one. The girl who traverses its spatial distances—past velvety slopes and steep, seaside cliffs—becomes, at the crest, a woman. But the ontological demarcation of girl and woman is less conspicuous; sometimes, it’s a blind turn, other times a sharp fall, and suddenly, you are wrested from that existence. But always, the girl you once were becomes a ghostly echo in the distance, deceptively close.

“Girl” and “woman” are arbitrary linguistic signs, whose meanings cannot be predicted from their forms, nor are their forms dictated by meaning or function. For that reason, their meanings spring from an imposed set of rules and lived experiences. “One is not born, but becomes a woman,” Simone de Beauvoir's famous conjecture goes. For a woman, looking back at her girlhood, she is conditioned to believe that biology is the basis for her categorization. Nagdadalaga ka na! is the bittersweet refrain of our mothers and grandmothers when they witness our burgeoning breasts and widening hips. Or else, Dalaga ka na! That shift in tense happens when the period of menarche arrives. But the root word dalaga is replete with its myths, illusions, and performances; in truth, not quite the sun-dappled hues of a Fernando Amorsolo painting.

And yet before we were dalagas, we were girls.

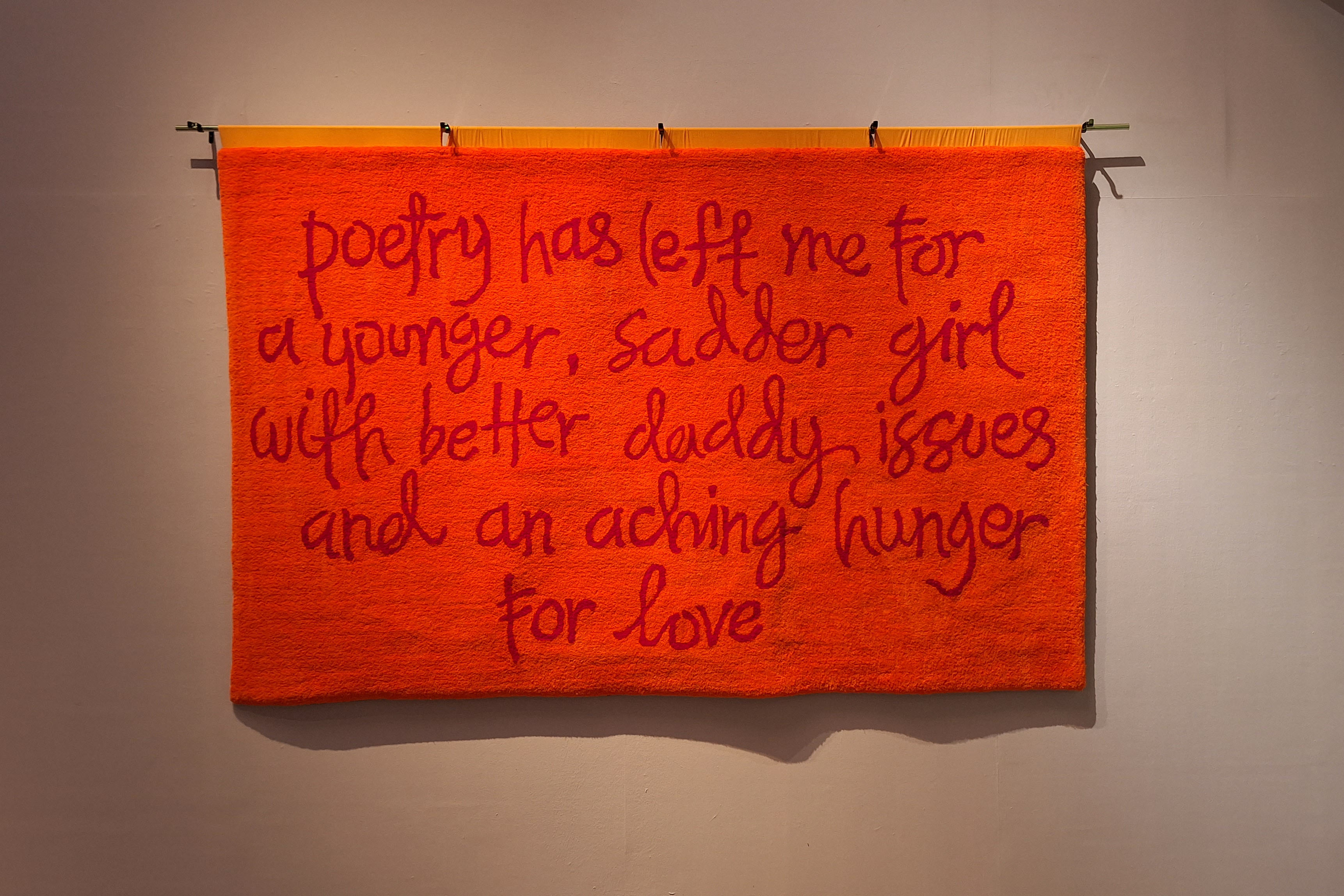

The girl is Marionne Contreras' main preoccupation in her new exhibit at Vinyl on Vinyl Gallery. The exhibit’s name “Poetry has left me” is a line taken from the show’s pièce de résistance, a piece of text art that commands your attention as it hangs from a rod, bright, bright red, and backdropped by a lush lavender wall. Contreras’ choice of an oversized scale seems to demand a certain kind of inescapable focus. The girl in question? Herself. Or at least the “younger, sadder” version of her, the self who is the subject of the piece which reads,

poetry has left me for

a younger, sadder girl

with better daddy issues

and an aching hunger

for love

During an artist talk at the gallery, Contreras shared that the text itself was a pocket-sized poem she wrote and rewrote in one year, turning the words over in her mind, “wallowing” over it, as she recalled. She considered this piece a kind of self-portraiture in words.

Much like her, I didn’t think I had it in me to be a poet. Maybe she, too, had scribbled words on a page and felt them heavy-handed after such emotional excess. Maybe the words were charged, but imprecise. Honest, but superficial. Way back when she was an art student, Contreras experimented with resin and fiberglass but didn’t think they were enough. She craved a kind of physicality that made objects more malleable and easily manipulated, thus her eventual studies with rug, thread, deadstock fabric, and yarn. Meanwhile, I still toiled over words as a prose writer.

We were no longer poets ourselves, but the words never left us. Instead, they moved into our lives and became permanent fixtures, the way a vase of fresh flowers is set and replaced over and over—delicious, fragrant, breathing. Perhaps the reason I was so drawn to this piece was this shared reverence for words. The poet Clark Coolidge said in a poetics statement in 1968: “Words have a universe of qualities other than those of descriptive relation: Hardness, Density, Sound-Shape, Vector-Force, & Degrees of Transparency/Opacity.”

Younger

Sadder

Hunger

Girl

There is so much longing in these words. Their phonetic closeness, all ending in the /ur/ or /ɝ/ sound, construct a sequence of circular depressions with each enunciation. The girl grows heavy, sinking with each two-syllable word, that the triteness of the last line, "for love," feels like an exhale.

In “To make a saint out of a part girl, part liar, part rage ball, part crier,” Contreras once again employs that phonetic repetition in the title itself. In this piece, she constructs three layers of tapestry, a “triptych” she called it, in eggshell blue, magenta, and tangerine. Contreras was inspired by topographic maps, depicting depths and elevations in the earth’s surface. In this case, ripples of thread cut across the linen fabric to signify ridges, peaks, cliffs, and valleys. Each tapestry is pock-marked with unidentical holes—tidy, amorphous shapes that allow you to see through parts of each layer, creating the illusion of depth. The title takes you back to the girl in question, anointed as a saint when the supposed truth is that she could be otherwise: a liar, a rage ball, and a crier. The piece materially sustains the psychic tensions and push-pull of our private truths: were we hellish or heavenly? This, too, Contreras revealed, is a self-portrait.

When interrogated about the holes, she said, “They have voids because I don't want you to know me fully, I want you to assemble the parts yourself. I want you to commit to knowing.” This could mean two things: on one hand, there are voids in our recollections, and omissions in our self-perceptions.

The topography of girlhood, for one reason or the other, does not linguistically exist in my consciousness. Perhaps it could be the fact that no exact language speaks to that particular experience. There are only the neutral words bata or kabataan, which do not capture our gendered bodies and histories. The direct translation for “girl” in Filipino is batang babae. But they do not carry the same existential weight as dalaga or dalagita or pagdadalaga, as it is warranted. Nor does batang babae or the all-encompassing babae seem to reflect the linguistic symmetry and nuanced interpretations of using “girl” or “woman” in certain contexts to underscore or subdue meaning.

Parts remain a mystery to me, and to my female friends in this country, who wish to see their girlhoods represented and verbalized. I would like to remember and memorialize the Catholic schoolgirl that I once was. Those years felt so slow, surprising, and short-lived. I balked at my own body and wanted nothing more than to be loved by my estranged father who smelled like Marlboro Reds. I snuck hand-written letters written on pad paper to a boy who looked like Diether Ocampo and said he loved me. I stole my mother’s red lipstick and delivered a soliloquy in front of a mirror on sad afternoons like a washed-out theater actress. I ached, I hungered for love. But that’s not all there is to the story.

Like deadstock fabric, yarn, and thread which are pliable and can easily be twisted, pinned, and glued, Contreras seems to suggest the ways that as girls we learn early on to become malleable for the male gaze. But that just as easily, we deflect. Like Contreras, I construct my topography with holes. In constructing each one, I confront them. With each word I use and discard, an image of myself emerges in a single sentence—memory turns into narrative into truth.

I remember Julia Roberts inside a bookstore in Notting Hill, saying to Hugh Grant, bare-faced in a powder blue cardigan, ''I'm also just a girl, standing in front of a boy, asking him to love her." I also remember what Anne Carson wrote in her poem “The Glass Essay,”

Girls are cruelest to themselves.

Someone like Emily Brontë,

who remained a girl all her life despite her body as a woman,

had cruelty drifted up in all the cracks of her like spring snow.

We can see her ridding herself of it at various times

with a gesture like she used to brush the carpet.

What does it mean to remain a girl? To evoke the girl in a woman's body? While the elegiac tone of “Poetry has left me” creates a sense of bittersweet adieu, ”the “girl” is, in fact, not dead. She continues to haunt and linger in Contreras’ art-making. The literal associations between her materials and organic forms (like flesh) create a distinct carnality, each one forming totemic evidence of the girl’s existence.

Because materials evoke certain sensations, there is an inherent tenderness to Contreras’ soft, undulating sculptures. Through the furry, visceral textures in “Poetry has left me” and “To make a saint out of a part girl, part liar, part rage ball, part crier,” we perceive a softer sentiment toward the impressionable girl she once was. That these pieces could have been carpet rugs or throw blankets reminds us of the ineffable comforts provided by a well-tended, matriarchal home.

In a way, a home she does make. The door is wide open, there are flowers, and the girl is making the bed. "I find beauty in her. By putting myself in her place, by being the subject and object of affection… she’s become my muse." With that—Contreras seemed to suggest—don't we owe it to the girls we once were, and still are, for giving us our magmatic longings and lessons?