The prospect of online exhibition shows and platforms has been particularly prominent in these extraordinary times. But a web domain is not nearly as restrictive as physical space, logistics-wise, or however else. As the art world is poised to go evermore digital than before, a question stands: should it emulate the experience of a physical gallery, or should it be something else besides?

Saying the Internet is a place of wonders is a near adage, and it was especially true for art when most of us were first introduced to the World Wide Web in 1991. Before digital art platforms and online art shops as we know it became a thing or were seriously considered, the ’90s saw the rise of ‘net.art,’ (the name is specific to the movement) an Internet-based art form available exclusively online.

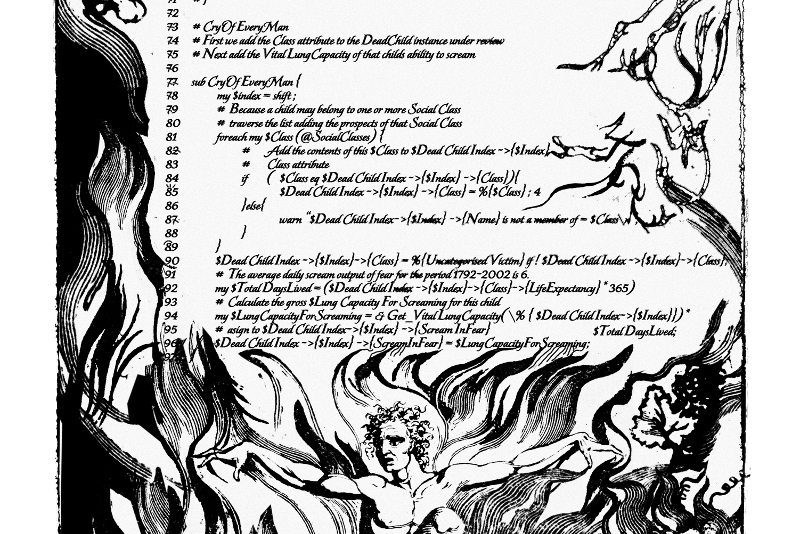

The ’90s was a critical transitory period into the new millennium, heady with a zeitgeist air that propelled movements and thinking in excited leaps and bounds. Artists, mainly Western on record, began to recognize the radical implications of web browsing for artmaking and, particularly, democratic distribution. In line with movements like installation art and street art, the foremost principle was to close the gap, with interactive artworks one URL away, utilizing code, scripts, and other Internet-exclusive devices that proliferated e-mail chains and web domains alike.

It was especially alluring as a new form of expression for artists belonging to the then-politically turbulent regions of the former U.S.S.R., whose fall coincided with the Internet’s mass appeal. The rhetoric surrounding net.art started to develop a radically political tenor, as writers and cultural theorists (many of whom were participating artists themselves) took it up to theory to fix the rising art form’s tenuous validity. In the wild, foundational imaginings of the movement, the agenda wasn’t to make aesthetically-pleasing artworks (explicitly opposite to what art agendas are thought to be). Net.art had less to do with the overall art tradition and history and more with exploring the novel, innovative forms of expression the Internet presented. It's something we still see today.

Net.art’s livid opposition to art history and its institutions, at least in principle, lashed back at itself, however. The general, escalating hype for the Internet precipitated the dot-com boom (1996-2002) when excessive speculations over the Internet-related companies led to substantial investments. When the dot-com economic bubble popped, net.art was just as swiftly swiped from the limelight. As Julian Stallabrass writes in “Can Art History Digest Net Art?” (a fantastic read and basis for much of this article), art institutions cut their losses, doubling back to familiar, reliable mediums following the market crash.

While the Internet went on achieving the accessibility and interconnectivity closer to what we know, Net Art (beyond the movement) hovered at the contours. As a genre that compasses a growing set of expansive and hybrid practices contingent on digital media, it stood outside the general context of ‘art’ typically conceived. Moreover, since Net Art didn’t fall under the usual “Art” category, the genre became more niche, especially as mass visual cultural production found its footholds in the now-ubiquitous media sharing platforms (Youtube, Instagram, Flickr).

However, Net Art can appear anywhere online, and that's the point. Present net artists can appear in your Instagram feed, such as GIFKids. Just last 2015, too, contemporary art figures Nicholas O’Brien, Sebastian Chan, Daniel Doubrovkine, and Orta Therox met at Artsy to discuss the many layers beneath the buy-and-sell of code as cultural objects. Even more, Rhizome.org, a leading site in digital contemporary art, just completed its Net Art Anthology last 2019, where most of this feature’s Asian artworks are from. The one above, Shu Lea Cheang’s Brandon (1998-1999) is the Guggenheim’s first-ever online commission, a web-narrative inspired by the brutalized murder of a young trans man, Brandon Teena (b. 1993) and Julian Dibbell’s “A Rape in CyberSpace,” highlighting the oppressive social conditions replicated in the Internet even at its nascency.

More from Rhizome’s anthology, which may be the closest to a digital archive of Net Art as of this writing, is Miao Ying’s Blind Spot (2007), a near 2000-word dictionary in which 2000 google.cn search terms are manually whited out if the words are censored by the government. Following the timeline is RMB CITY (2009, active until 2011) by Cao Fei, a fictional Chinese city built in the online virtual world, Second Life whose process mirrored the breakneck urbanization in China at the time.

It may be too soon (or, maybe, too late) to say that Net Art is reentering the public sphere in a big way. But as technologies rush in, so do more forms that add into Net Art’s expansive array. The anchor photo is a still from the kolown.net Brunswick Project, a collage generator without any form of human intervention. Either way, as long as the Internet continues, somewhere deep in the web is Net Art.

For Zero Hunger PH

We thank the artists Kiko Capile and Manix Abrera, as we happily pledge part of the proceeds from our “Athena” and “Mandirigma ng Dalam-Hati” tote bags to Zero Hunger PH’s crowdfund. Zero Hunger PH is a youth-led movement aimed at creating and distributing food bags to the homeless and families at risk, following the ECQ’s suspension of work.

To learn more about initiatives like Zero Hunger PH, Help From Home PH is an online information hub that connects people who want to help with people who need it the most.