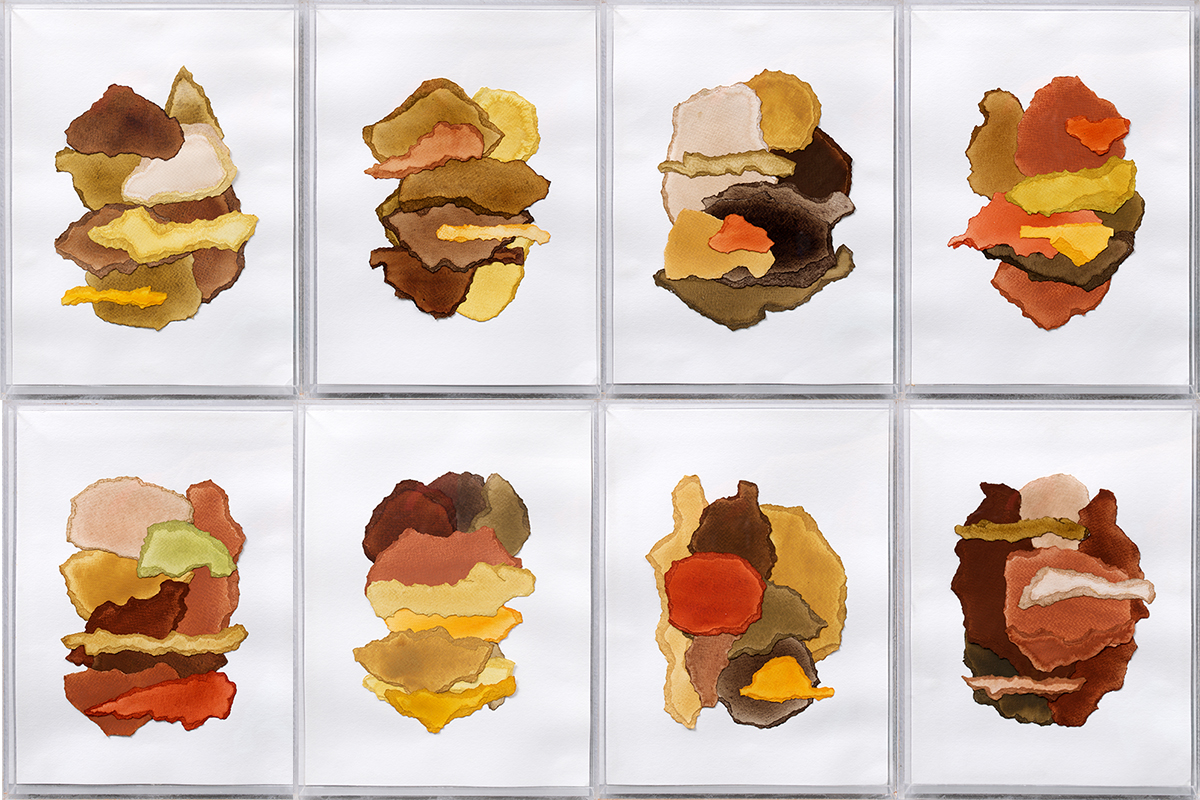

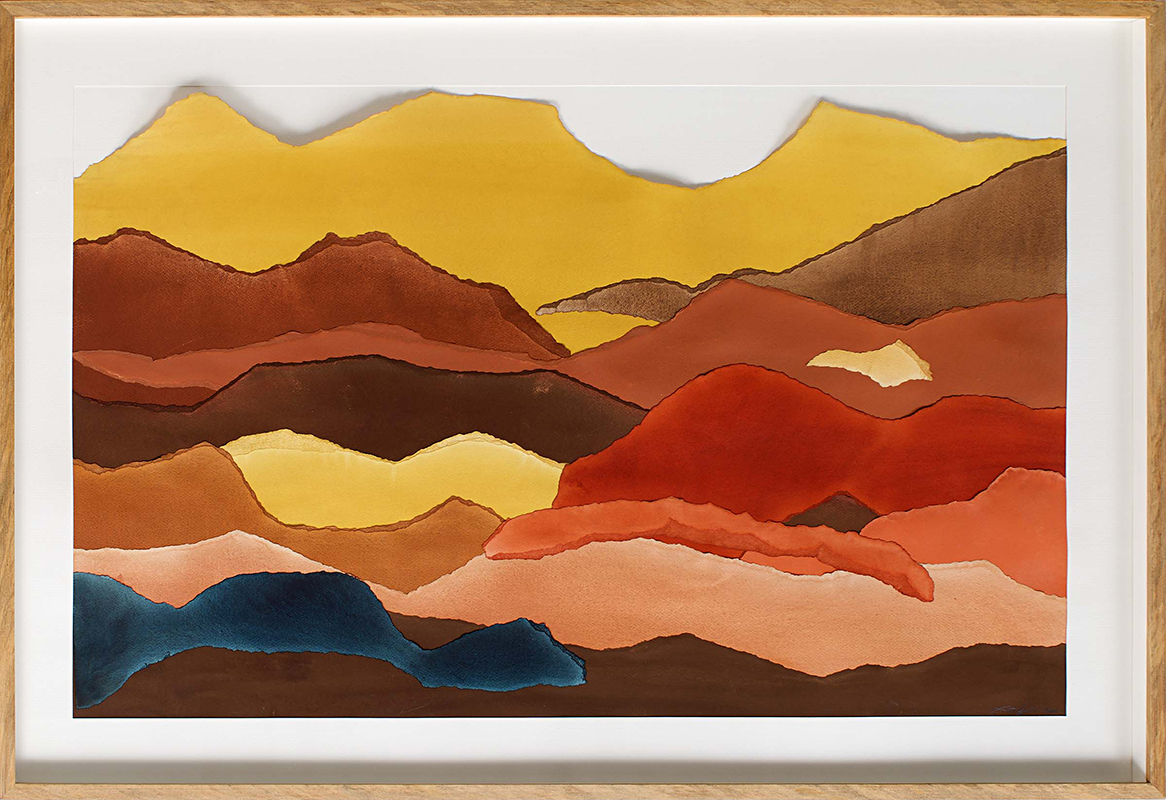

When gazing into the cresting shapes of Kat Grow’s collages, you might find it surprisingly easy to luxuriate. Textured with natural pigments she made on her own, present in Kat’s art is a haptic force. Look at how the edges line and cut into each other, how the vibrant hues in their bodies pare down to (or strike up) another mountain row, registering snippets of a larger whole.

Anyone familiar with Kat Grow would know that integral to her art is her process. The firm, rhythmic presses of a pestle against substance, the resulting crunch. The first sight of froth as liquid swirls into a boil. These essential undertakings Kat involves herself in with her art, they’re not so much creating as it is a cultivating, nurturing, a “working with” material. It can be didactic in the way her process can teach patience, though that’s not quite it, either, and we certainly can’t leave it at that. To leave it at patience suggests ego, but it’s the very rituals Kat performs that enacts the radical dispersal of it, spreading ego so thinly across each pigment and granule that it becomes almost entirely effaced.

That carries with it a certain spiritual heft, doesn’t it, an outlook that doesn’t occur as a need quickly enough. It’s not from a lack of thought that has the best of art slip past our attention. It may be the way we’re agitated to think that has art fail us, aggravated as we are by present conditions that can, even subliminally, compel one to assimilate any and all things to make sense of the goings-on: the social and political unrest, the pandemic. How often do we gravitate to ideas that affirm suspicion, and what we already know?

It’s limiting to treat art as a social balm, or to think of it as something to limn just how dire the situation is, or that it ought to; rarely are we predisposed to allow it take and exceed these concerns as a way to help recalibrate our thoughts. This interview happened by e-mail correspondence, one that stretched into the weeks that had us witness, among others, press freedom put under threat. I feel it’s important to mention that Kat was incredibly accommodating throughout, as I didn’t know much about process art right off the bat. Rereading the interview (and for the nth time), I keep thinking about the poem “Least Action” by Kay Ryan, and how Kat’s process is akin to that “incremental resurrection” Ryan has us imagine. It goes:

Is it vision

or the lack

that brings me

back to the principle

of least action,

by which in one

branch of rabbinical

thought the world

might become the

Kingdom of Peace not

through the tumult

and destruction necessary

for a New Start, but

by adjusting little parts

a little bit — maybe turn

that cup a quarter inch

or scoot up that bench.

It imagines an

incremental resurrection,

a radiant body

puzzled out through

tinkering with the fit of what’s available.

As though what is is

right already but

askew. It is tempting

for any person who would

like to love what she

can do.

Cartellino: Making art materials yourself isn’t an idea that comes naturally to most. What called for the shift in your practice at the time?

Kat Grow: I always found peace in doing repetitive, structured tasks. In college, I explored processes that entailed such actions for my undergrad thesis. I would cut up a ton of plastic wrappers into little bits and stick them to an epoxy armature to create sculptures, paste shredded plastic wrappers on boards, deform and reshape tin cans, and create miniature houses with recycled corrugated boards. I continued that practice after college and in a mentorship program (Artery Mentorship). As I was still staying in Metro Manila at the time, I was submerged with concerns about capitalism, urban congestion, and the ecological dangers of our waste-management and waste-generation. I was so influenced and informed by Metro Manila life.

However, when I needed to come back to my hometown in Sta. Rosa City, Laguna, where everyday experience is different, I ultimately stopped that practice because of the contrast of living experience and limitations with space and logistics. Truthfully speaking, I also needed to earn money to support myself. I didn’t make money from my trash-based art, and it was hard for me to get shows, sadly.

I decided to focus on another language I loved: watercolor. I started conducting workshops at different venues like coworking spaces, cafes, et cetera. I felt that I needed to know the most minute detail about painting for me to confidently teach. So, I did my research into the history of materials and the technicalities of how to make them. Little did I know that it would have me plummeting into rabbit hole that I wouldn’t mind staying in until now!

Now my practice is really more about the traditional art of creating artist materials. Preparation: making pigment from natural resources. It’s still a conversation about how I negotiate with materials (as how I did with garbage).

C: Did you find ideas for your art coming differently to you since then, too? A specific scenario that comes to mind is when you got your hands on Taal’s volcanic ash. How do materials like that factor in?

KG: How I create art is a slow process. If an event presents materials to respond to, I usually take time to observe. But for the example of the Taal’s phreatic eruption, I have not actually made anything about it yet. I had only looked at it with my amateur microscope. For that case, and for some of the materials I find, collect, and sometimes receive, they spend a lot of time with me resting in glass bottles, boxes, and containers. It may be because I feel like they do not speak to me yet, and so I give them time to be familiar with and find their place in my collection. When ideas strike, I open up all the little corners of my studio to revisit pieces of rocks and ask if they will let me bring out what they want to say.

A valuable teaching I’ve learned is that nothing is actually mundane; everything has purpose and will manifest in time. A small pebble, an egg yolk, a leaf, all may or may not want to be a medium of our intervention and creation. We artists respond and create but we must also respect these objects that we use, treating them with the same value as we treat our thoughts because everything — worldly, human, and heavenly — are connected. Everything can be treated as sacred; nothing is ever mundane.

C: There’s a kind of catharsis—a release—that comes with completing a piece. Being so involved in the rituals of your process, is it any different for you?

KG: Artmaking is an everlasting process, but a bigger part of the journey for me is in the silence and noise of making pigments. One’s head (cognitive), heart (motivation), and hand (action) all participate in the transformation or preparation of materials. If they are all in sync, then everything created is born out of a holistic process and spiritual consciousness. In this light, you can say that an artwork is somehow an optical manifestation of a prayer. But you don’t just say one prayer and say “That’s it! It’s done.” You repeat prayers and write new prayers every day. The artwork also finds for itself new meanings as time goes by. The physical and spiritual energies an artist has imbued into an artwork just transforms; it does not get lost.

C: That’s an interesting point. Making with organic material tends to wrest them from what they’re typically thought to do. Suddenly, for example, egg yolks are not just for eating. Do creative instances like these point to a different way we consider the role of an artist, also?

KG: Egg yolks are commonly used as binder for egg tempera, it’s just that artists nowadays do not have to crack open an egg themselves to mix egg yolk with pigments to make paint. It’s nothing new, and it does not necessarily have to be a creative instance or process. It’s just that many artists nowadays only know paint as something that comes out of a tin or plastic tube. Pounding rocks, grinding and mulling pigments, boiling leaves, burning bark or chicken bones — all of these are gritty and laborious tasks. All these actually ground me in my relationship art. Most times, I ask myself if I truly am an artist, but I am always, always sure I’m a laborer and a craftsman.

C: What have you found in your studies on sacred geometry so far that resonate with you and your art?

KG: I love that I am learning about sacred geometry (and some of Islamic visual art) during this time of quarantine. This subject and alchemy are both rooted in Perennial philosophy. Perennial philosophy tells that all forms of sacred and common knowledge and all religions, all their truths come from one single Universal truth. As an example, sacred geometry is an underlying universal language across different cultures. Something I learned recently about a certain shape you get by combining two circles — an almond-shape or petal-shape or a “vesical piscus” (vessel of fish) vessel pertains to messenger as it relates to Jesus Christ in Christianity — is something I appreciate in these online classes I’ve been participating in.

However, to be able to understand what lines, shapes, dots have to do with each other is not a widely accessible knowledge when it should be! Sacred geometry reflects interconnectedness and explains the inherent symbolism of many images across different traditions and heritage. The subject isn’t new, but I have not found any classes on it here in the Philippines when it’s highly important in traditional arts and crafts and in history. One of my dreams is to be able to teach it in the future.

C: Two years ago, Gajah Gallery held Medium at Play, a group exhibition of female Indo artists with this amazing curatorial premise: “What does it mean to give agency to the material, to follow the material and to act with the material?” The responses of the artists, given their shared Indonesian context, were almost unanimously gendered. What about you? How do you think you would have answered?

KG: Thank you for telling me about that exhibition. I think the curator directed the overall theme of the show to be about gender studies on purpose. I think I’ve already given my answer with how my reaction would be about the quote you have given. So, if I were invited to such a show, I would perhaps make something reflecting the dominant and receptive behavior of materials. I think one of the artworks I’m about to create which utilizes the creation of verdigris pigment would be a nice example. But I think that’s as much as I could tell you without giving it away.

All-in-all I believe in unlearning a lot of things artists are taught as norm or standard. Just like our disconnection and alienation with certain schools of thought and spiritual beliefs during this modern age, there actually are essential technologies and truths in traditional processes and teachings. Just like how we’ve forgotten to plough and till the land, we’ve forgotten how to live with the Earth. We basically live with foreign things, so how can we effectively bring out truths that way?

C: That’s true. Trash-based art seems to occupy the opposite end of that spectrum, though. Trash can be a very social material. It’s waste, residue, laden with predetermined codes that restrict ideas on the matter to a specific context — in your case, Metro Manila. Comparing you how you work with natural materials now, and then shape or transform them according to what they say of their potential, it seems almost like a regression. Is regression the right way to understand this practice and your belief in unlearning or defamiliarizing what we know?

KG: I find it funny to have started with making art using plastics and detritus. Yes, trash is charged with social and political meaning. After all, trash is identity. However, I think my practice really needed to go the way it did.

There is truth in the word “regression,” if it refers to a “return.” However, unlearning does not always equate to a “return to a lesser developed state.” By unlearning and relearning, we are able to form a marriage between both old and new, which I believe is a far better mark of progress than a practice intentionally blind to the past. So, for me, it just makes sense to go this route. In doing so, I can proceed with a better understanding and relationship to the natural world that sustains us. It's an exciting journey — learning traditional crafts and old knowledge with modern or contemporary eyes — I feel more human.

C: I’m most familiar with your works from Unmapping Territories. Is “unmapping” similar to “unlearning” here? How did collage play into that aspect?

KG: Unmapping Territories was really an introspection into my identity, heritage, and memory. Tearing up papers, staining them, and creating a collage was the best way to visually show the act of destruction (unlearning) and creation (relearning). The series entitled “Recollecting” was the blatant example of unmapping.

It consisted of shapes torn into the likeness of the disputed islands between the Philippines and China, collated to form ambiguous new shapes. The question is, what is there to recollect? Recollecting means to collect again. Who has the right to collect? Who has the right to own? Recollecting also means to remember, and, when broken down, RE + MEMBER means to come together again as part of a whole. In that case, we are just one people, right?

Right. Kat Grow is also the founder and owner of Pinta PH, a local craft store that sells handmade native paints, raw pigments, and studio materials for your artistic needs. Keep an eye out for its reopening post-quarantine. Kat's works, “In Exchange of,” “Navigating Promises,” and “Emphasis on Changing Tides” are available at the Cartellino shop.

_Natural_Pigment_on_paper_.jpg)

_Natural_Pigment_on_paper_.jpg)