Sam Feleo’s best work happens after 10 PM. Under fluorescent light, from the perspective of a Zoom call, the aged white walls of Sam’s home studio are a sharp contrast to her sprightly demeanor. Her synthetic crystals blanket this borrowed room, and between their faint glimmer and the bright flash in her eyes when she speaks, the former is what hints at her battles with insomnia. “I’m just being honest. It’s manageable,” Sam tells of her collage-making, “Under low light I can work; it’s analog paper I can carry around and cut while my son is sleeping. So I don’t sleep.”

Since the birth of her three-year-old, Sam has been a stay-at-home mother. The aimless days succeeding lockdown for her did not turn out as empty as it did for others; instead, the stretch saw her roles become more sharply divided. “With a child, there’s no other time to concentrate,” she continues. “And that ‘mom guilt?’ Totoo talaga siya. Yung kailangan mo magtrabaho pero gusto makipaglaro ng anak mo. Ano gagawin niya? He definitely taught me how to sustain work amid frequent distractions. Buti nalang he’s already at an age where he can entertain himself, even if it’s for ten minutes at a time.”

The lone fact that Sam is an artist and mother is not a direct cause for concern. Rather, it’s that the two invariably stack high costs of living. And, when denied, privileges, even those as basic as funding and healthcare, play a part. In many ways, though, Sam’s battles are much like yours and mine. It’s about sleepless nights, hard nights: about paddling abreast with time, the bracing hold of ambition, and how quickly, adamantly, it registers during youth as undying self-belief. Sam, perhaps more so than others, was set up for a streak. She graduated cum laude with a degree in Painting from the UP College of Fine Arts in 2008. The last painting she finished, however, is dated a year later, for which she placed as a semifinalist in the Metrobank Awards for Design and Excellence (MADE).

Her next entry happened in 2016, a solo show in Archivo. What happened in that eight-year gap? I asked. It’s a struggle when you’re new, Sam tells me. “Wala kang pera. So where do you start? Buying materials is hard enough. I didn’t do my exercise in the artworld after college, not even group shows. Andami ko din kasi gustong gawin.” Sam instead juggled part time jobs: teaching, gallery work, fashion retail. “I wanted quick money, to move out. Be free. Do whatever I want.”

But art was never out of the question for Sam. When recalling intense working periods in her life, Sam often uses (and conjugates) one word to describe them: turbo. “As if I wasn’t swamped with work enough, I applied for an MFA in 2014. Na-miss ko talaga mag art, pero di pa din ako magpipinta. It bored me. I realized that I couldn’t just reenter the art scene. When I applied for the MFA, I applied without a considerable portfolio. Alam mo ginawa ko? A month before the application, tinira ko. Tinurbo ko yan! Medyo sabog talaga. I just drew and did collage, para mabilis. I was just lucky that Archivo took notice of my new works. The charcoal drawings were my ticket to my first solo show.”

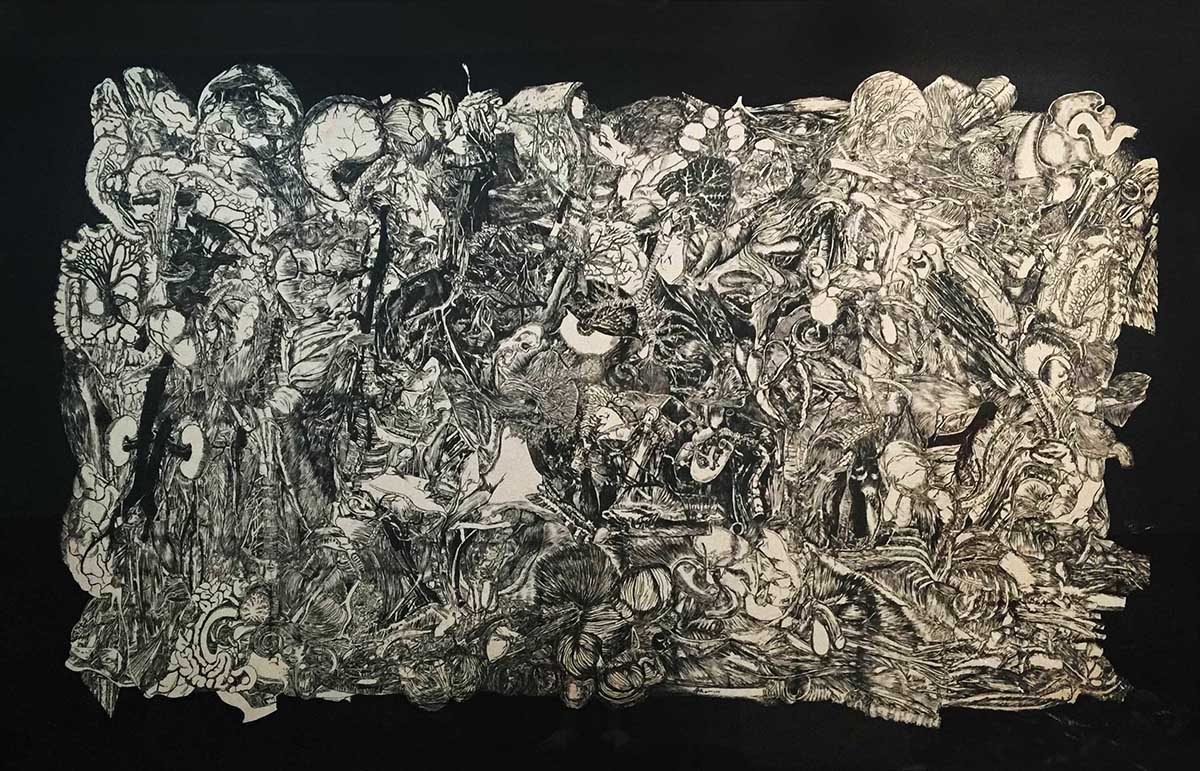

The Archivo exhibition is titled 132134, a numerical sequence, denoting permutations within a defined set of parameters. For the show, Sam exhibited a maximalist suite of collage works and drawings (one of which was 12 feet tall). Writer Gian Cruz noted the show as “autobiographical” and “performative” in equal parts. It’s much like “life’s paradox,” Cruz goes on, “of keeping everything together on the surface when things are actually breaking apart.”

This tension has long been a constant for Sam, a tendency she describes as a movement between accumulation and release. It’s a structure that rives against the unity of control her medium is expected to assert, and the effect is astonishing: every drawn hand, every mingled body appears to writhe under the weight of their shared compositions. “A confluence of forms does not come easy for me,” Sam continues, “the process is anxiety-driven. I see putting things together as a way of dealing with the distance I feel in my life.” It is, in other words, abstraction, a means of pruning details to achieve a sense of the whole. This is a process apparent, too, in her speech. When Sam speaks, each thought is treated with equal attention, then they dissolve into one another such that it becomes a matter of perception to see them leveled flatly as she does, on a plane.

“2016—tinurbo ko yung year na yun. I was teaching part-time in 2 different schools, doing my MFA, and mounted my first solo show. I got some positive comments from my professors and peers, but also comments like, ‘Andami mong ginawang works tapos iba’t ibang style. Nagdrawing ka. Nagcollage. O, asan na yung sculpture?” Sam recalls. “I needed that, na hindi siya ganung katight. I’m hungry for critical feedback like that kasi I always want to refine.”

Hungry. Was part of taking the MFA to be reintegrated with your peers? “Yes,” she says, “Who else do you run with after college?” By this time, the straight path taken by her batchmates had more than coughed up dividends. Each decision they made shone lines on their CVs, secured for them gallery representation and eligibility for artist residencies at remote corners of the world. “So may feeling napag-iwanan ka.”

But 132134 signaled a shift in Sam’s momentum, a prodigal return for her to art. The Ayala Museum had a job opening, while the CCP put out an open call. She applied and, by the fourth quarter of 2016, learned she was accepted for both. She was slated to start in March 2017 as a project coordinator between the Ayala Museum and the BPI Foundation. For the CCP, The Horizon of Expectations was scheduled that year in August. Sam had the time, the money, and had just then begun incubating her first batch of crystals in a makeshift lab.

Then, by February 2017, Sam discovered she was pregnant. “Nabuntis ako with PCOS? Ha..? How did that happen?” Sam laughs, “It wasn’t part of the plan, but my partner and I were happy to find out.” Didn’t it put a damper on your plans, though? “I was going to work with food-grade chemicals. My OB was opposed; I couldn’t risk it. I think I developed post-partum depression later on. Living that turbo life, then having to slow down.”

In 2018, Sam had to let go of her job at the museum. “I think that’s when I truly knew I had depression. Before becoming stay-at-home, I was doing group shows pregnant, taking my MFA pregnant, preparing for CCP pregnant. Yung asawa ko would ask me, ‘paano mo gagawin lahat ‘yan?’ Sabi ko, after ko manganak in September, in those two months, I will mount my second solo on time in November. Crazy, diba? Ganun talaga yung mentality ko kasi dati. Gusto kong gawin lahat. I was naïve to the challenges of mothering. The first several months was hell—breastfeeding and not getting sleep was the worst, but it wasn’t just the physical pagod but the mental, too: the emotional stress of not having time to do anything other than mother a child. It changed me. I now know the extent of my strength. I realize now na di ko kaya sabay-sabayin.”

“I was excited about showing in an institution like the CCP, pero iniisip ko din yung investment ko. Paano ko siya babawiin financially? It was a non-selling show, but I had to do it. My family was supportive of me. But I spent my life savings. I drained it for that show.”

Before its launch in November 2019, The Horizon of Expectations had been postponed twice. In the time Sam prepared for the show, her son was sent to daycare three times a week, her crystals, meanwhile, laid submerged in pails and basins across every available room. To make one, Sam explains, one first needs to fire a ceramic core and then submerge it in a cooked solution with 5 – 10 kilos of a chemical powder mixed in. Since 2017, Sam has cultivated 200 of them, in batches of 50 at a time. “I like material experimentation, kaya siguro ako gumagawa in mixed media. I love discovering effects and possibilities with materials. I think the artistic aspect of crystal growing comes with the infinite possibilities in the cultivating process, and when one can exercise some control, encourage growth, come up with unique forms—yun yung art doon.”

For a crystal to grow to the size of a fist takes nothing less than months. It was only during the show’s run that Sam got to see their compositions in full: an immense show of polychrome, crystalline teeth, so phenomenal were they that it seemed to enlarge the CCP. In the imaginings of Crystal Sandbar, the installation resembles a coral reef, its vibrant array of colors illuminated by spotlights. The reason why it’s mounted that way and why corals are so uniquely fluorescent, Sam explains, is because corals release colored chemicals that act as a sunscreen from underwater heatwaves caused by climate change. “It’s a visual alarm, an intense need for preservation that went unnoticed.”

The crystalline forms are themselves phenomena, which form and dissolve according to the environments they are in. The Horizon of Expectations, its title, curiously lifted from reader-reception theory, was about springing future audiences from the dominant cultural and social codes that surround a piece, in part an exhortation to see things anew. For Sam, it was to look past the anthropocentric purview, to look at the evolution of phenomena according to their own molecular geography.

Their bodies. As of this writing, Sam has turned down five group show opportunities and a solo since late last year. She’s currently being evaluated for lupus, she explains, an autoimmune disease that causes inflammations and rashes across her body when subject to stress. “Papahinga muna ako. I’ll enjoy my time with my son, lagi ko nakakalimutan that rest is also productive.” When asked about whether this would affect her work, Sam lightly shakes her head. “I just want to focus my energies on developing unique and mature works. Art and motherhood I can manage, basta hindi ko lang i-turbo.”

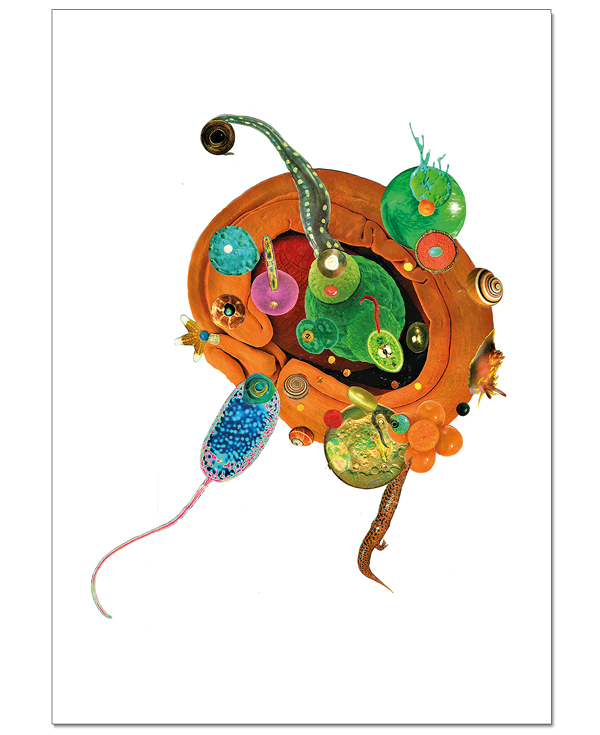

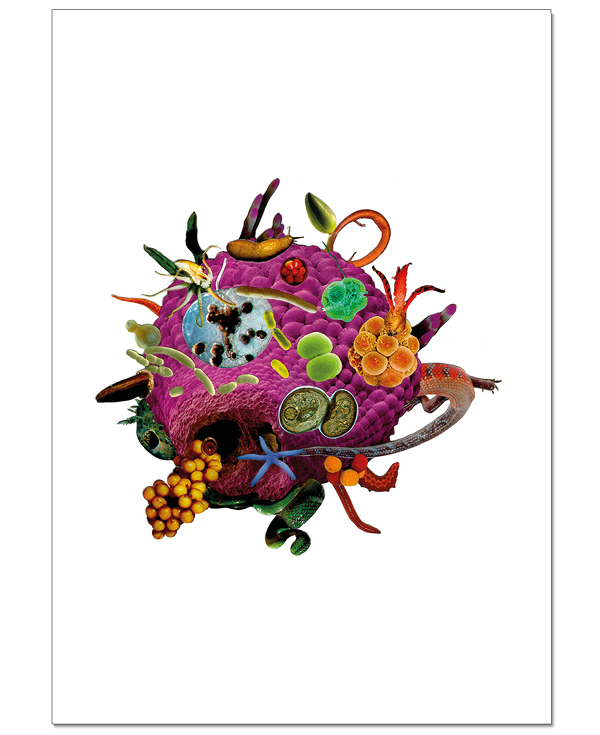

Slowness invaded Sam, its insistence is now something she firmly and admirably espouses. And it can be no more evident than in her present art. Her crystalline works have since been reconstituted as limited-edition terrariums—the secret to restoring and preserving them, she found out, was a particular kind of resin. Meanwhile, her latest collage series has a certitude to them, dignified as it is clinical. Specimens, they’re called, the images are emphatic, jarring, spliced hybrids of mollusks, microbiomes, and vegetal masses put under scope, on petri dishes. Dense, floating images that retain the same vibrancy of color as her large-scale works. Yet in place of immensity, the weight in these collages—these scopic anatomies—are unlike ever before. Staked in them, and to such precise degrees, are slow movements, so slight at the fringes of perception.

Sam has never been more unruffled. Even when seated still, she’s already in motion, with her best work still lying ahead. “I don’t panic anymore about my accomplishments as an artist. I’m not looking to chase after every opportunity. I tell myself: it’s not a race. It’s a marathon.”

Scopic Anatomies is a collaboration between Samantha Feleo and Cartellino. It runs until February 6. For inquiries about the works, click here. For more of Sam's works, visit her behance. She is also on Instagram.

For artist mothers, UK artist Lenka Clayton founded Artist Residency in Motherhood:

"Artist residencies are usually designed as a way to allow artists to escape from the routines and responsibilities of their everyday lives. An Artist Residency in Motherhood is different. Set firmly inside the traditionally “inhospitable” environment of a family home, it subverts the art-world’s romanticization of the unattached artist, and frames motherhood as a valuable site, rather than an invisible labour for exploration and artistic production."

To learn more, click here.