This interview was occasioned by the recent release of FREE-Lances Volume 1 2020 – 2021 Online, a free digital publication engaged in discussions surrounding freelance work in the arts sector. Return any time to this link or the one at the bottom to sign up and receive a copy.

This edited transcript is a conversation between Cartellino editor (C) and the FREE-Lances team: Editor Renan Laru-an (RL), a researcher, curator, and Public Engagement and Artistic Formation Coordinator at the Philippine Contemporary Art Network (PCAN); Managing Editor Con Cabrera (CC), a visual artist and independent curator, as well as instructor for Critical Perspectives in Art at the University of the Philippines and podcast co-host of Isang Oras with Zeus Bascon; and Creative Director Jaime Pacena II (JP), a visual artist, a video director for advertising and the music industry, a part-time teacher at Asia Pacific College for the Multimedia Arts, and the in-house curator for CANVAS.PH and Marahuyo Art Projects. Jaime is also the founder and creative director of multimedia art collective Bliss Market Laboratory (BMLab).

Cartellino As mentioned in the volume’s introduction, the freelancer’s image has gone from being a paid mercenary to being the cheapest and most efficient contractual worker. This may be why freelancers often have diverse portfolios and skillsets, a characteristic that, for me, is often construed to enforce the idea of the “self-sufficient individual,” rather than demonstrate some institutional lack. More, having unique skillsets provide upward mobility. For instance, a curatorial skillset is what large projects like the Yamagata Triennale1 need.

But, like the project by Yoshie and Nozaki, what’s discussed in FREE-Lances is how these creative ideas are leveraged, all while being mired in logistic and financial difficulties. There are discussions, too, about art management and the tangled processes of work and collaboration and uplifting the minority. You yourselves are independent curators; at what point did you realize the issues you have been experiencing were as embedded as these?

Renan Laru-an When you decide to get into the artworld, there’s that expectation of precarity. It’s a problematic position to take on, but that’s the reality of the context. One is discouraged from getting into arts because of all these histories of precarity. Even when considering creative work, it’s not enough to carry a certain sufficiency. There’s already that baseline from which every art and cultural worker operates.

It’s been a matter of saying, “I can’t work like this anymore.” That’s the pivotal point, always. But this idea of saying “I can’t work like this anymore” doesn’t happen once. It’s a perpetual subjectivity. And that goes into a context in which you also think about how you wanted to work in the art world. But it’s not just about positioning an alternative or going against certain ways of doing things. The continued participation in this way of working is also a way in which you could perform a proposal of, well, “Hey guys, we have to get our shit together. We have to do things differently.”

I think it’s also operating from a renewed relationship with freelancing, at least in the artworld or creative sector. As the job is not regular, the assumption is that the freelancer is an aggressive individual: raket lang ng raket. But it’s not just about money. This is not about nostalgia or taking a heroic position. It’s more about how there are other ways we can exchange. In a way, it proposes to slow down capitalistic intentions. This is also a position that I at least take. When we talk about freelancers’ or independent contractors’ rights, the dominant discourse is always about fair compensation. This is all beautiful and good and well-meaning, you know, but the reality of the context is there’s always kakulangan, kulang sa budget, etc., and there are other forces involved.

Con Cabrera Sa akin naman, at si Renan, we’ve been talking about freelancing and lahat ng mga heartaches namin sa trabaho. Matagal na. So, it was very natural for us to come up with a project like this. Ako, I look at it in a feminist perspective of making visible the invisible work. ‘Yung lagi rin pinag-uusapan especially ngayon ‘yung radical care, radical work… ‘di kasi nakikita ‘yung process, kaya hindi rin nila alam paano i-quantify, paano bigyan ng equivalent na presyo, halimbawa.

But when you talk about it, it makes something more tangible, almost. At the same time, there is a lot of invisible work in art production and the artworld. So isa itong paraan para gawin nga ‘yung visible, also to make people understand and realize that you have to be compensated in a just manner. It takes a lot of skill, time, and energy to do this type of work. I’ve always been exposed to artists, kasi ‘yun ‘yung set of friends and community ko, and we talk about the process na hindi babayaran ng gallery kasi very object-driven tayo. Output. Paano pa kaya ‘yung art managers, paano ‘yung curators, the other people who work toward having this object? At the same time, we freelancers take on tasks na sometimes hindi na natural sa extension of work mo, pero mayroong pressure for you to accept it because it entails compensation.

So, after having a corporate job ng matagal tapos tumigil ako [in 2012] to do full-time art, ‘yung mga klase ng raket na tinanggap ko, sobra niyang iba-iba. In terms of the tasks needed, ‘yung compensation... eye-opener ‘yun lahat doon sa whatever we think of freelancing now. And it’s very relatable. At matagal ko na ‘to ginagawa. You don’t ask how come one thing is not being talked about, ‘di mo itatanong kung bakit hindi pinag-uusapan. What you do is find the people who you can talk to about freelancing. You just try to find the tribe you have relatable experiences with, and then, somehow, come up with something na magkakaroon ng platform for you to discuss. The importance of the discussion and talking about things is sometimes taken for granted, pero it helps us understand our own situation and then come up with more concrete action. Even for our personal… Kahit after nito, next time, I will demand for fair compensation — ‘di na ako magpapalugi. Those small things. It’s also a product of connecting with people in the same boat as you.

Jaime Pacena II About how FREE-Lances started at paano pumasok ‘yung BMLAB, it’s because me and Con know each other from way back. We know our work backgrounds. BMLab is a small freelance collective, but for this project, ako lang ‘yung involved. Iba rin kasi ‘yung trabaho needed to be done for this online publication. And, actually, it was the Japan Foundation grant that initiated it. So, already, there’s that freelancer dynamic, as Renan mentioned, raket lang ng raket: “Uy, may grant, it could help us start this idea.” Matagal na ‘to, this discussion among freelancers, people in art management, even curators. The sensibilities are there. Me, I’ve been a freelancer for a long time, and I do a lot of things as a freelance individual, so nandoon ‘yung nagkaroon ng BMLab. This came naturally to me, too, making visible the invisible. I think the important part is to ensure the dialogue, the idea, naintindihan naming tatlo, kaya nga nag-materialize siya into this.

Between artworld reality and expectation, relationships, and the job

C Okay. I can bite into that idea of expectation. If I come into the artworld as an artist, for example, I would know the stakes and would still go in willingly —it’s either I make it, or I don’t. But with most contributions of this first volume coming from curators, I’m shown something different. With curation, one individual is usually made to be on top of all these things. But, interestingly, the volume turns away from that idea. Compared to instances like mine — writing — it’s often just my labor. I expected it would be different for freelance curators because of your mobility; I would think curators have a lot of say in how things go. But that’s not the case?

CC The reason why there are so many independent curators is also a product of the system. There are few institutions that can absorb or create jobs for us. That’s why we’re freelancing. And then ‘yung leveraging, that’s a product, too. It’s not that we need to; it’s a matter of we have to for us to create jobs for ourselves. The artworld is personality-driven, reputation-driven. Renan?

RL Yeah, curating, freelancing, and then ultimately the neoliberal... These are the dirtiest words. It’s so hard to clean these words. Especially with curating. I think the curator has been the quintessential performer of these things, as you’ve teased out, in its historical formation as an identity. It’s that in addition to other inherent burdens it carries within the art system, as it is formed by artists and other factors. On that note, I think freelancing and curating have changed so much, especially with how these two unfold in the context of the Philippines. What seems to be a shared characteristic of freelancing, as you know, you would only freelance in the same way that you would only do independent curating — or that you would — if you have some sort of safety net. That’s the dominant kind of fiction around that. If you look into the realities of it, the early curators, the early set of participants in the artworld who became quite famous or reliable, are individuals who went abroad and came back to the Philippines. Another example is the individuals who could access state universities and have these characteristics of upward mobility.

But that generation or context seems to relate with these things as if there’s a secret that can have them keep on. As if there’s something magical about it. But I think there’s another force within the cultural sector now that’s coming to say that the artworld doesn’t have such trade secrets. So, there’s that batch, that emergence of sensibilities and sensitivities coming out to say that this is pretty much a DIY thing. That the trade secret is that there’s no secret. It’s not a regulated business; therefore, everyone can participate in this. It breaks that kind of silence — that you need to have cultural capital before you get into the art world. I’m also saying that because for the past five or ten years, for example, there are more individuals participating who have been coming from different demographics. It diversifies the context. And ‘yun nga, balik lang doon sa FREE-Lances, I think by coming out as a vulnerable freelancer, it inaugurates a new link where individuals can bond. Hindi na siya certain background na pwede magiging source of solidarity. For example, it’s not about coming from UP or Fine Arts or coming from specific cliques.

I also want to say that, within the international conversation, doon usually nahihirapan for colleagues and friends from Indonesia or similar production contexts, kasi minomonopolize ng discourse na “you all have cultural capital,” “you all have social mobility.” Therefore, an independent curator based in Berne or Berlin is assumed to be on the same passage of struggles as a curator or artist living in Jogja, when it’s totally not equal.

C I’m reminded of the essay by Taufik Darwis,2 when he recalls Indonesian theater of the 70s to 90s as anti-establishment… that kind of militancy is quite prominent and has been for quite a while. To go back to Con’s mention of radical care, now the direction has this ethical turn. Certain buzzwords in the volume — negotiation, arts management, tools/weapon — meanwhile, point toward educational reform.

But that’s not exactly easy. Then there’s that part in the essay by Riksa Afiaty3 — and I’m paraphrasing here — where she writes: “can you imagine how difficult it is to explain the emancipatory value of art, to stakeholders?” There’s this impression on me that you [curators and freelancers] are backed up against the wall. How can you push for alternatives when output and sales have such premium? I think it was timely for FREE-Lances to have come about in a time of a pandemic. As many have said before, the inequalities have been laid out, and people are on the lookout for alternatives.

JP Isang magandang takeoff point doon is that a lot of people started talking about it during the pandemic. We had pockets of meetings and conversations among us. Me and Con would talk to each other, Con would talk to Renan, and there are other friends. Somehow because of the nature of who we are in this, what do you call it — ‘yung ginagalaw nating lahat — we have a care for it? Siguro kaya curators noh? We have this idea we want to protect or at least discuss. Among friends din, mayroon concerns bawat isa. Siguro magandang itanong kay Con at Renan is, why these contributors? One reason is that they worked with artists and curators before, and pareho ‘yung sentimiento. Maybe Renan and Con can share their rationale. Renan, nag-iba ba ‘to?

CC Nadagdag lang.

JP ‘Yung kay Greys, Tanya, at Sakura?

CC Greys, Tanya, and Sakura are part of a group exhibition na icu-curate ko for Drawing Room na na-cancel. So ‘yung imagination ko doon, it will be a discussion between them. Kaya sila ‘yung artists [in the volume] na may creative output. Ang mode ko lagi, work with your friends. So lahat din sa list na ‘yun friends ni Renan, friends ko, given na limited yung amount ng grant namin, alam namin na may ganung limitations, we rely on our personal relationships to help complete the project. Social capital, kung baga.

RL It also allows us to see the informal mutual aid system that exists and is always activated by certain agents within the sector. So, for example, a curator would find ways to provide new gigs to artists who lost opportunities to exhibit and sell works. ‘Yun nga, masyadong imbricated ‘yung professional and ‘yung personal. As teased out in Riksa and Taufik’s works, there’s some kind of fixation or currency with devotion and obligation that sustain work and exploitation, for example, in art. So, the currency of care within the sector means that you know the conditions of your colleagues. And you also want to address that by realizing projects and producing jobs. May — what do you call this — motivation. There’s that domino effect at the end of the day. That’s one reason for inviting artists as writers into the publication. That and, of course, these individuals, matagal ko na silang kakilala. You know the history of your conversations and consistent ‘yung pinag-uusapan: that state of labor and management. By inviting them to share their experiences, you provide a link into further discussion about the concrete issues that produce these conditions.

On art management, careers

About management… at the end of the day, La Salle and Ateneo have arts management; UP has curatorial studies; and every year, a new batch of arts graduates come out of these schools and join the workforce. Again, there’s that assumption of a secret to the art world, to art management. The professionalization within a Philippine art system is really, really conservative. You see institutions and museums that have, for the longest time, not hired curators. We’ve been operating for ten years in the sector, but there are no job opportunities that can offer tenure.

And this is a good discussion point because there’s a disjunct between the skillset being produced by an individual for ten years, artist naman or hindi, and more standardized job opportunities. The only job opportunities that are robust ay galing sa National Museum, for example, because lagi sila may posting for curators. And it’s ISO [International Organization for Standardization]. Pero wala nag-a-apply, or kung may nag-apply man, they wouldn’t be able to fit into the job because of some standardized requirements. I don't think there are job opportunities for a curator in the commercial art scene locally. Kaya siguro nagiging sharp and highly professionalized ‘yung curator, because puro paloob lang. You keep improving yourself so you can work for the next project. The joke sa freelance curator is that you produce a project for you to produce another. Parang artista lang, diba? You’re only as good as your last performance!

CC True. Maganda, actually! ‘Yung sinasabi ni Elo, ‘yung na-touch on education. Very important ‘yung piece ni Theodora Agni nga, ‘yung radical schooling on arts management.4 Kasi, nagtuturo ako sa Art Studies, nag-e-MA ako roon. So, of course, nakita ko ‘yung klase ng education system mayroon sila, na may pagkukulang tapos ganun din naman sa programs halimbawa ng La Salle-CSB at sa Ateneo. Nag-guest ako sa isang class ng Arts Management, tapos ang tanong sa akin, kasi wala masyadong discussion ng Philippine context sa FREE-Lances, alin ‘yung mas resonating doon sa eksena dito? It’s very Indonesian naman talaga ‘yung eksena, so lahat ng namention ni Agni roon sa discussion about Indonesian arts management, very resonant dito sa nangyayari sa atin.

Tapos ayun nga, gaya ng sinabi ni Renan. We feel that. Dahil lang din, parang, ang nagiging museum curators ng regional museums ay librarians, mga clerks, ganyan, kasi kailangan mo ng Civil Service, kaya rin walang nagna-National Museum. At the same time, may creative thinking din or temperament ang curators na ayaw pa-tie down sa establishment o kaya having your own voice sa ginagawa mo. Those are factors kung bakit din hindi rin nagpapa-subsume sa mga institutions kadalasan ang mga ibang independent curators.

Reaching out

C It’s not that these aren’t unsubstantiated, but I would also like to ask, “okay, these are the problems. ‘What now?’ ” Maybe it’s because I’m young that I would still want to eke out some solution, hopefully without it ending with [gesticulates] revolution. What I mean is, in terms of how you talk about envisioning the future for art practice — how art can still matter and offer different points of view — how under threat is this?

RL This concern comes and goes throughout your professional life. It always reminds me of exhausted conversations in certain public talks, for example. I don’t know where this happened, but one audience asked the speaker, “why aren’t you doing this or that?” And the speaker replied that this question had been addressed in a previous project of theirs. You can’t tell us we’re not working toward the betterment of our community. What I want to say is that we need to reach out more. Not just to people, but also to history. What are the things that people had done before? What are the initiatives and failed projects that people tried to get off the ground, pero walang traction from the community? There’s a fragmentation in that. That’s why we keep on asking these questions and tend to be exhausted at the end of the day, and we feel hopeless because of these things and relationships with our history. Kasi we’re keeping things in our own silos, that we’re convivial and all that, pero hindi pa tayo nakapag-reach out talaga. The practitioners in FREE-Lances have been there for quite some time. It’s about reaching out to these types of individuals and practices that would allow you to mobilize your thoughts into action. So hindi lang empty call for solidarity, but how to maintain relationships to turn projects into movements, kung baga.

It’s also about reading, you know? Minsan, we’re too busy with our own projects that we don’t see how one project can be situated in a larger ecology of things. Or even one individual. Or certain groups of individuals, for example. So, kung baga, ‘di na natin kailangan gawin ‘yung ginagawa ng iba, kung ginagawa na nila ‘yun. What we need to do is amplify. Support. Mas ganun ‘yung approach ko doon, mas practical siya. Going back to what seems to be a divide between freelance and the institutional — and we all are engaging with the institutional, therefore, hindi siya oppositional na standpoint. It’s more like we need to open up more. Yes, negotiation, but at the same time, it’s also how we approach each other. I’m saying that because maraming misjudgment with the freelancer, may misjudgment with the institutional. Pero very complicated din ‘yung position ng institutional, for example. How do we really understand each other’s practices? What do they really mean when they do this? In the same way, gallery owners are in a very complicated situation. They can’t do anything else because they have to think about their rent. But this reality is affecting how you socialize with people and their projects...

JP Agree ako roon sa sinasabi sa conversation. The position of FREE-Lances is that art is not just about the visible market out there. Wala tayong escape doon eh, we all sort of work or negotiate our way through this. Global din ‘yun, global din ‘yung negotiations regarding the art market idea. But what’s highlighted in FREE-Lances is it’s not just about that.

The true negotiation happens within management, ideas na ‘yung nanggagaling doon sa FREE-Lances: freelancers, individuals working toward certain ideas they’re trying to pull off even with small logistics and resources. It matters because it can be bigger than this. We work with what we have, at maganda ‘yung point of view ‘yun na kailangan makikita ng iba. In this ecology we belong to, there’s this discussion, and there are people who work in this discussion.

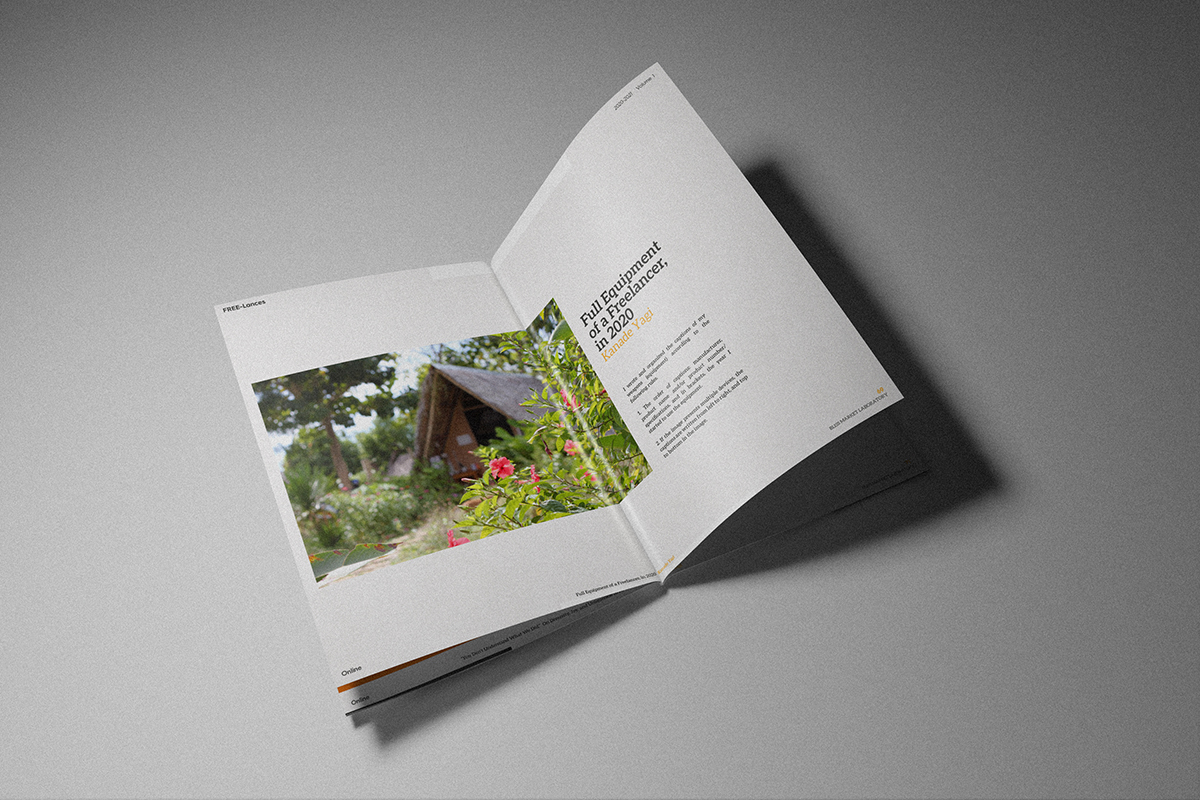

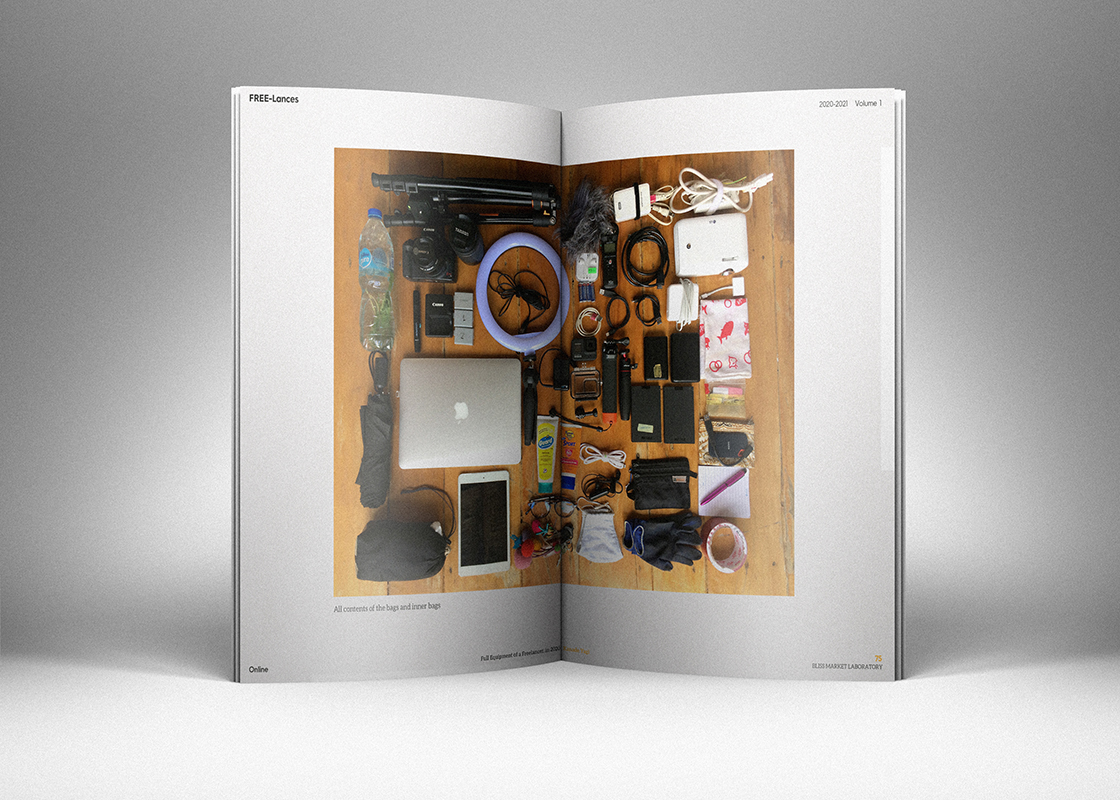

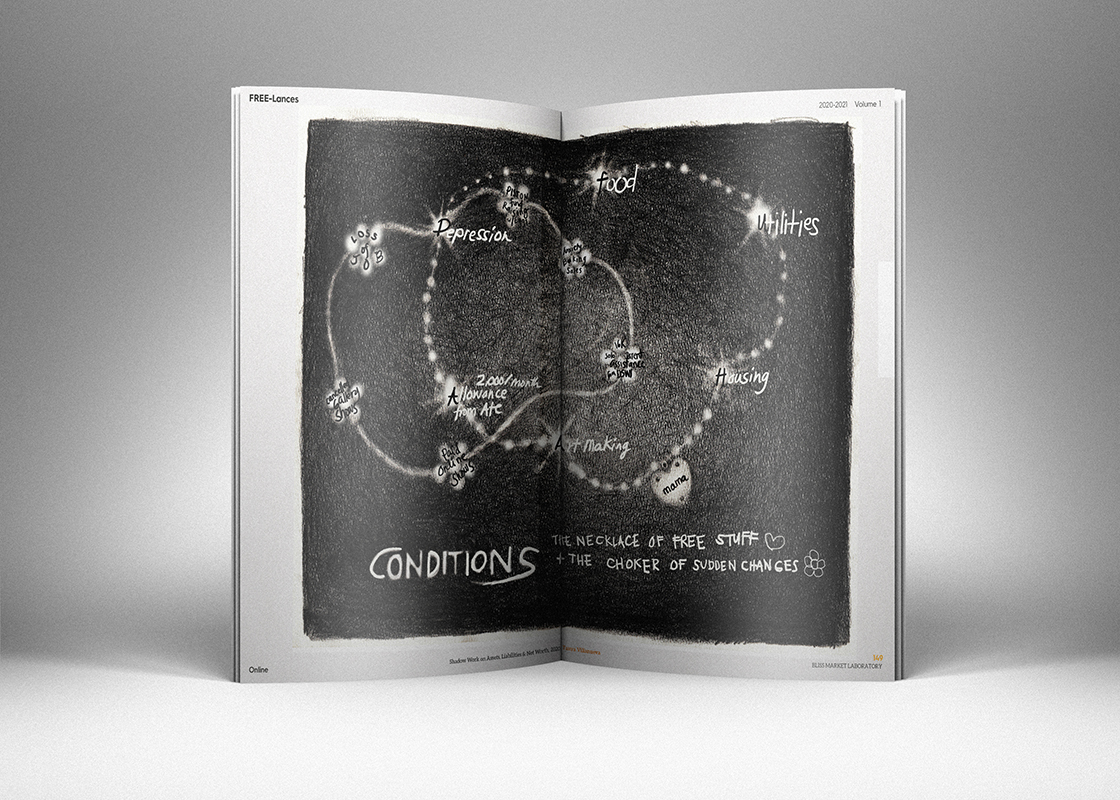

Hindi lahat ng artists are made. For example, Tanya’s concerns are legit.5 All of those things she felt then contributed. And somehow iniimbestigahan niya sa sarili niya, sa sarili niyang proseso. It’s all part of this — ginagalawan ng isang individual, isang artist who works without any artist funds or is not secured, that’s part of the negotiations. And, again, trying to talk about different conditions din. With Kanade,6 she opted to talk about her conditions through working with what she has, in a condition na ilagay sa kanya ‘yung sitwasyon. Lahat ‘yun valid concerns in talking about how people are trying to navigate this.

I think isang concern din na lumilitaw during the pandemic is ang tahimik ng arts scene in terms of how to deal with the workers. Kasi ang suporta, ang iisipin mo, ang secured individuals lang during that time are the ones secured sa market. Even museums, even individual freelancers, curators, I was thinking, “paano ba tayo gagalaw sa time nito?” So, I think ‘yun ‘yung isa sa mga nag-ignite ng discussion, para kausapin din ang mga kapwa freelancers and curators who work in their individual spaces and ask them, “kamusta ba kayo?” Kasi, ‘yun, nobody asked. The galleries remained — in Manila, for example — closed, to artists, to these kinds of discussions. Museums also have their own problems in terms of paano nga ba i-negotiate yung objects inside at ang gusto nilang sabihin to engage with an audience. Pero tahimik kasi... well ‘yun ‘yung napansin ko. In my end, ‘yun ‘yung pinag-uusapan ko during that time. Not necessarily COVID-related, pero ‘yung sentiment.

Freelancers of all kinds

C I can’t help but feel at times, too, that it’s hard for people in general to situate themselves in larger contexts; I myself fail to see it. FREE-Lances gives us a framework we can use. Thank you for that. Now... sorry, I’m not sure how to push this further, I’m not exactly — I’m no Patrick Flores, basically.

CC Actually, even curators working in institutions freelance. Okay din ‘yun sana pinag-usapan, napansin namin ‘yun dahil may survey kami ‘di ba. Pag nag-sign up ka may tanong: “Are you a freelancer, yes or no?” Andami ring sumagot na working in a company or institution but freelancing. Maraming ganun. There are many mutations of freelancers dito sa atin that even the more established cultural workers also freelance. Siguro it’s not also about abolishing ‘yung pagiging freelancer, kasi I don’t think it will happen. But at the same time, mayroon pa ring may kailangang gawin. ‘Yun nga ‘yung sinasabi mo may resolution — mayroon bang ganun? Siguro, it’s not even institutionalizing the profession kasi that would entail many other things and disadvantages. Siguro ‘yung recognition of that person, ‘yun nga ‘yung palaging nasasabi, “I want to be seen,” ‘yung mga ganyan! That’s the human part of freelancing, to feel that what you do is acknowledged and essential.

At the same time, dahil iniinitiate ako nung start ng pandemic ‘yung visual artists’ directory with other friends, I know also how hard it is to build a community. Talagang mahirap siyang gawin with the nature of the artworld that we have. Plus, kahit ayaw namin aminin, ‘di namin maamin na kailangan namin ng pera. You need to have funding for a project to fly. Even for a simple directory. So, maganda ‘yung naging groundwork na nakapag-gather kami ng 900-plus names of artists, pero hindi na umaandar ‘yung project sa ngayon. We don’t have a website; we don’t have the money. So, having a community that is present, if that’s what freelancing community is sa imagination natin — unionized, ‘yung mga ganyan-ganyan — that’s very far from the reality ng context natin. Tapos mayroon pang mga socio-political roadblocks, so hindi na kami makapag-gather ng information because of issues of privacy, et cetera. The same goes with this project. We can’t have a listing of freelancers, but we can have these conversations through this publication. So, ‘yung form ng publication, flexible siya enough to have this pseudo community na pwede kaming mag-reach out, at the same time, product din siya that the artworld acknowledges, in a way.

JP Tsaka it’s not just talking to freelancers, marami rin kasing nasa organization or institution or isang kompanya na working, katulad sa mga nag-signup. At some point, freelancing is also about being independent. Independently realizing your ideas, na hindi halimbawa sa isang institution that you work with. For example, hindi lahat ng gagawin ko konektado sa CANVAS. I work as a curator for CANVAS, pero hindi lahat ng ginagawa namin doon ay bagay sa naiisip ko on a personal level. NGO rin ‘yung CANVAS, so technically I can only do so much. But as inquiry to mga ibang bagay, I do a lot of things besides. So, we want to talk to those kinds of people who, aside from ‘yung konsepto na hindi sila magawa ang gusto nilang gawin, hindi sila supported. This is the target audience na important to gather. Kaya maganda ‘yung nabuo nina Renan at Con ‘yung konsepto ng survey: gumamit ng paraan to create this community, ‘yung, sinu-sino ba kayo?

So, may hope to do another thing to discuss more. Because we would know who we’re trying to talk to. Aside from a group of friends, sinu-sino pa kaya? And, I think, with the different backgrounds we have, konektado siya in the end. Si Renan ‘yung maraming international connections. Kami naman ni Con, we’re teachers. We want to communicate it to the next generation of freelancers.

Community building, artist-run spaces

C I think that’s fascinating. If you’re going into art, you’ll invariably be a freelancer. It’s great you mentioned communities, too, Con, as I’m tempted to ask. There are a lot of connecting threads — though with some salient differences — to artist-run spaces. As far as my knowledge goes, not many of these spaces are known to be sustainable. Did it occur to you that FREE-Lances is similar in that regard? That you’re forming communities, hashing out identities, putting out a platform for people to speak, and maybe eventually put out creative output that they would otherwise not be able to do?

RL This publication initiative is quite serious on the fact that we don’t want to hold on to it as if we’re the founders. It’s something to be taken on by others as a kind of relay. Seriously, if Cartellino or if another group of people want to take on editorial, the design, then so be it, and we will be here to support. We’re losing the idea of competition in freelancing. I mean, regardless of people, whatever we say, the sector is real because there are actual things at stake. Also, the reality is that there are only a few jobs, only a few grants. But we are quite serious that it’s a medium, in which if Shifting Realities in Indonesia wanted to take it on for the next issue, let it be taken on. I say that because I think — and maybe Con could reinforce me on this — we’ve learned our lessons from artist-run spaces. Collectivity, single-handedly — or two or three people — running a space, it has proven to be not sustainable, and not just sustainability in terms of finances; it may also prove to be not sustainable in terms of relationships!

So these are the realities. It’s not just the physical reality of sustaining artist-run spaces or an initiative. The precarity is very real and visceral. It takes a toll on your body. It takes a toll on your mind. Your relationships. At least for me, may assumption ako that we can call a spade a spade in terms of these spaces. My point, as pointed out in the essay of Riksa, is the idea of land-ownership and the capacity to be able to rent a house. I mean, ‘di naman mahal mag-rent sa Jogja compared to Berlin, but still, not a lot of people can afford a place to be an art space.

We have to take communities seriously. That’s one thing. At the same time, we need to get out of certain assumptions of what community is and what communities look like, and how communities are formed. Because these assumptions, these myths, at a certain point, they crumble. And you see through it, after the damage. So, it’s more of a question of how do we get into a room na may equitable position tayo, regardless kung saan tayo nanggaling? And the assumption is, art should be that space where there’s that equity, kahit sino ka man, diba? But the reality is not. So, I think, mas ganun sana. As pointed out in Riksa’s essay, hindi equal ‘yung pagpasok sa room ng participation. The landowner still has the upper hand.

CC Maganda rin ‘yung conversation kasi roon kay Meta Moeng7 sa Cambodia, kasi siya naman ‘yung landlord, in a way — dahil siya ‘yung nag-provide ng rent ng space. But ang interesting doon sa twist of the story is nag-close ‘yung space niya. Kasi hindi na nagwo-work ‘yung energy. May mga ganung factors. At the same time, ito rin ‘yung parang common sa aming tatlo. This is a curatorial gesture, it’s not an exhibition, but it’s a product of that. Of thinking and moving. And for me, artist-run spaces are those types din, kung baga. Same strand of thinking, it’s just that nasi-shift kasi ‘yung terrain, at naiba ‘yung need. At tsaka, natututo ka rin sa history, natututo ka sa mga mistakes ng iba. So, para sa akin, tama naman is Renan. Let’s call a spade a spade. The artist-run space has its own form and terms of management. Pero maganda rin to acknowledge, gaya rin sa sinabi ni Agni, art managers are produkto rin ng mga ganung klaseng institutions, and we learn from those. Karamihan din sa amin, at some point, na-involve sa artist-run space, collectives, initiatives, galing din kami sa mga ganun. So, to acknowledge the history of art management through those types of spaces and platforms, but at the same time, veering away from ‘yung form na iyon. Kasi, naiba na ‘yung mundo eh. What is space, ‘di ba?

1 Renan Laru-an. “‘You Don’t Understand What We Did.’ On diversity, joy, and uniqueness in arts management: a conversation with Kris Yoshie and Miki Nozaki,” pp. 6 – 7, 20 – 25, 50 – 53, 66 – 67, via internal hyperlinks.

2 Taufik Darwis. “How to Become a Freelancer in the Contemporary Performing Arts?” pp. 54 – 65.

3 Riksa Afiaty. “Curricular Changes,” pp. 121 – 133.

4 Theodora Agni. “Arts Management, the art history of shifting realities: a conversation with Theodora Agni,” pp. 110 – 115.

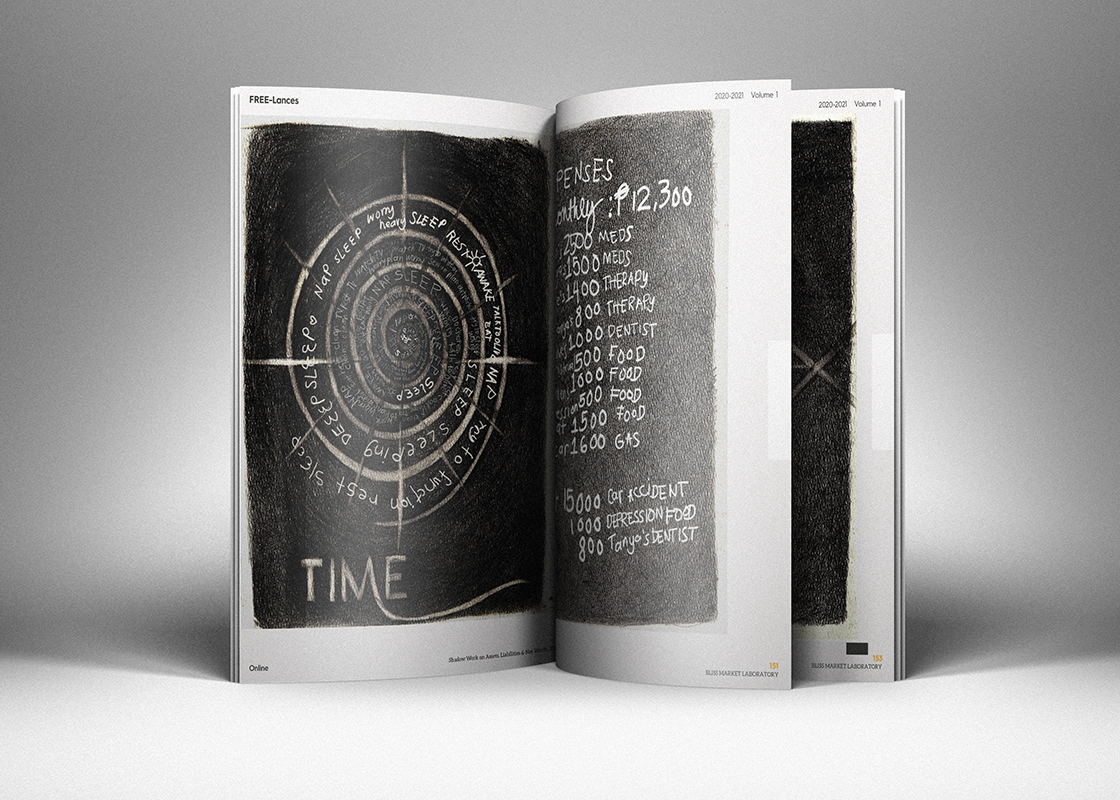

5 Tanya Villanueva. Shadow Work on Assets, Liabilities, & Net Worth, 2020, graphite and digital drawing on paper, pp. 146 – 153 (full spread images).

6 Kanade Yagi. Full Equipment of a Freelancer. 2020, pp. 68 – 109.

7 Meta Moeng. “Invisible Turns to be Visible,” pp. 116 – 119.

Enjoyed this conversation? FREE-Lances has just recently joined Instagram. To sign up and receive a copy of their first volume (we highly recommend it), click here.

-800-1200.jpg)