In a time of red-tagging, climate disaster, spiraling economic downturn, as well as staged political blunderings aimed to distract – often poorly – from these pressing matters, the role of art today seems comparably singular, obvious. To crisis, art must do what it can to divert it. I will not be listing here the manifold ways artists and cultural workers have been addressing this, however, except to mention that such positions have been taken and that there are many more still to take. Such is the silver lining with underemployment.

Crisis, as though it were unimpeachable, is too self-evident. The maxim that doom is imminent is too well-defined. To imagine coherently a world without crises is to assume that a world can cohere at all. To the negative connotation of this, Fisher, Jameson, and Badiou have posited as much, granted that crisis can be interchangeable with what causes and propels it. It’s worth mentioning that many think along this trajectory. It is hard not to: most people working in the arts are already demystified with systemic oppression; it’s only natural that a history of thought is readily available to explain it. Natural for everyone in the workforce and their mother, suppose. Nothing sells newspapers faster than disasters. And there has been no greater source of them throughout history than the West.

The impression, it seems to me, is, has long been, the quiet tendency to doubt the corollary of knowing about systemic oppression: that one’s creative work can indeed inspire in others equally generative practices, if not more. What was dispiriting about the popular reception of NFTs when it boomed was its striking allure – that income was not suddenly just possible, but seemingly effortless, considering that taste, when put in a feedback loop, can now be algorithmically written. This idea of the literalization of art, 8-bit asset or not, is credited to the writer Dean Kissick, whose point attaches to another of his observations: “So much bad figurative painting, and not enough abstract thought.”

This is not to say that many Filipino artists fall under this. Rather, that it has become too easy to fix into language the ones that do not, and too quickly is it assumed that these are the only divisions. Interlining the present crisis is a crisis of another kind, and of longer standing, around which – as is often insisted – our lives have been organized: the crisis of disenchantment, pertinent to the arts, abetted by late capitalism. Personal disenchantment is closely guarded, saturated with irony, or is twisted to be articulated or expressed as such to make it easier to explicate. Creative genius, in this generalized master-rhetoric, belongs to the one who can see it all too clearly – as if literally – such that whatever luminous image produced is certain to reiterate present suffering, though we know from sorrow that sorrow would survive it.

The anxiety to make a point of one’s being of crisis is overwhelming, and too hurriedly pathologized. The trope of the young historian looking at the world askance is exhausted; it would behoove him to extract joy in his findings. What happened to the supposed intransigence of art, where did it escape to? How might one find it?

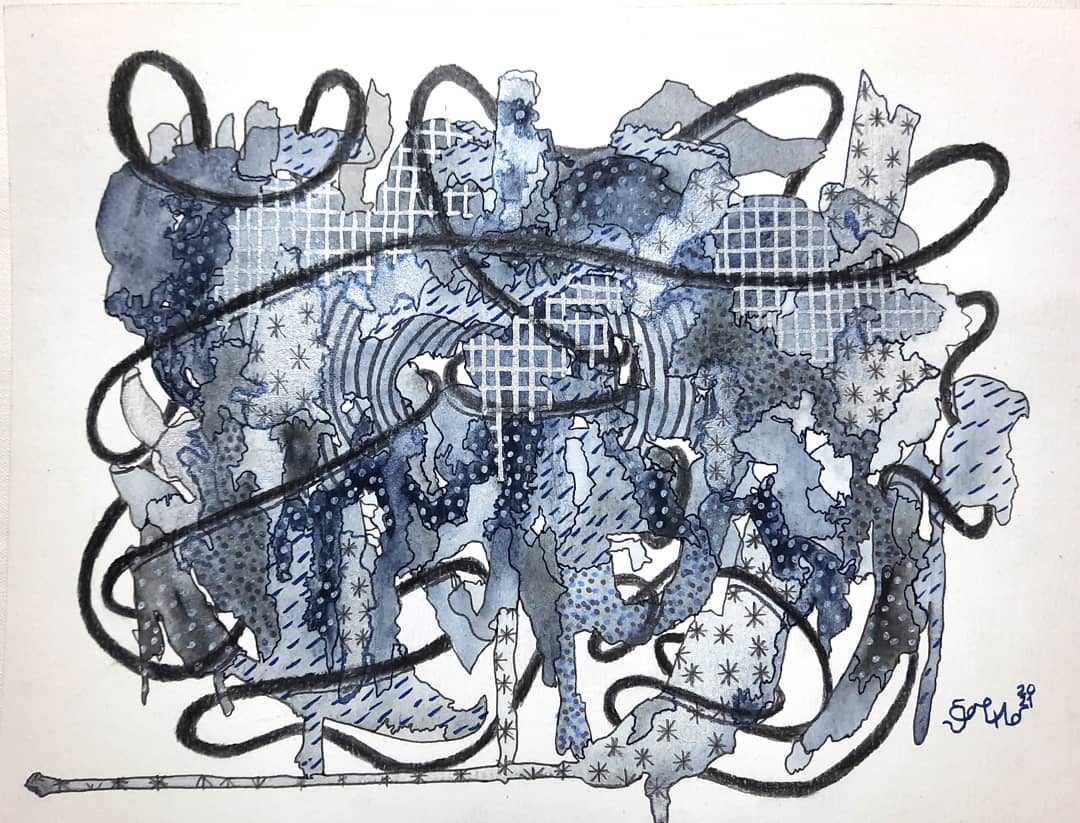

The manner through which Denver Garza’s Containment series is illustrated might suggest a point: a potpourri of thrumming, unmoored shapes circumnavigated by a long strip of line – in one instance tied by it, in another, hardly at all. Pronounced in variations of this line is the impossibility of the carceral task. The elasticity of the form is rife with associative possibility – any foregone conclusion, the colonial gesture, even, is demurred by the impression that the work had simply gone and elaborated itself, and in too mutable shapes for the mind to assimilate where the hand had deviated, what it was it had been up to. Intimated is the sensation of being engrossed – experience, here, as inchoate as the self processing it. The work suggests conviction, the need to reconstitute itself.

Containment I is a personal metaphor for crisis, of loss, and of travel. I live to see it changed. In the intransigence of art lies the possibility to reinvent one’s life through. That one can project oneself so easily is not to be made the virtue here, but that there remains the space to make room for the poignancy of an individual life. To encounter it in the work of Denver Garza is a pleasure. But this artist is one of many, all presently living. There is no guarantee for art to be seen this way; what is political and aesthetic in art is not so easily separable; and that behind a process of art expressly of joy is a person, in our contemporary moment, of dare. If one were to allow for surprise, then one might agree with this much: the question of how art navigates crisis would take lifetimes to carry.