Continuing with Cartellino, from this month’s Prints Made in May, works by Printmaking for the People or Prints para sa Bayan members Joyce Caubat, Ina Palacio, Amiel Louise Rivera and Saya Villacorta’s speak to the struggles and steadfastness of the Filipino people in the face of rampant sociopolitical injustices.

Formed in July of 2021, Printmaking for the People (PTP) is a collective of cultural workers, educators, activists and artists engaged in creating prints that reflect the Filipino people’s current conditions and aspirations. The group was founded by Jona Yang, a full-time activist and the serving Secretary-General of Advocates of Science and Technology for the People (AGHAM), who herself began printmaking just before the Philippines went into lockdown early in 2020. Caught at the height of the pandemic, the collaborative platform began as a small online chat group, exchanging ideas and printmaking tips, and have since been printing individually, sharing their works through and with their respective organizations both digitally and through the post.

Finding common ground in printmaking, the members come from different sectors and affiliations. Ina Palacio is a full-time primary school teacher of visual arts. An activist for the last four years, she works with Sama-samang Artista para sa Kilusang Agraryo, Artist Alliance for Genuine Land Reform and Rural Development (SAKA).

Joyce Caubat is a full-time instructor of Contemporary Filipino Arts at the University of Santo Thomas High School. Active since college, she has engaged in a range of solidarity activities and campaign practices, most manifestly in the creation of protest posters. Today, she is a member of the Alliance of Concerned Teachers (ACT).

Full-time student of sculpture at the University of the Philippines Diliman, Amiel Louise Rivera has been a practicing artist since 2018. Her activism began in 2019. Although she struggles to identify herself as a full-time artist-activist, yet, her works pivot on the axis of current socio-political issues.

Saya Villacorta first immersed herself in the local street art scenes of Manila and Cavite back in 2012. Starting off as a freelance visual artist, working predominantly on murals, she has since shifted trades and become a graphic artist and tattooist. It was in 2017 when Villacorta acquired tools and materials for printmaking, and began to teach herself to make prints.

As part of the inaugural online release of Prints Made In May 2022, curated by printmaker Marz Aglipay, Caubat, Palacio, Rivera and Villacorta submitted fine art prints capturing the ideals and ideas of the group as well as things that had moved each of them in their individual commitments to activism.

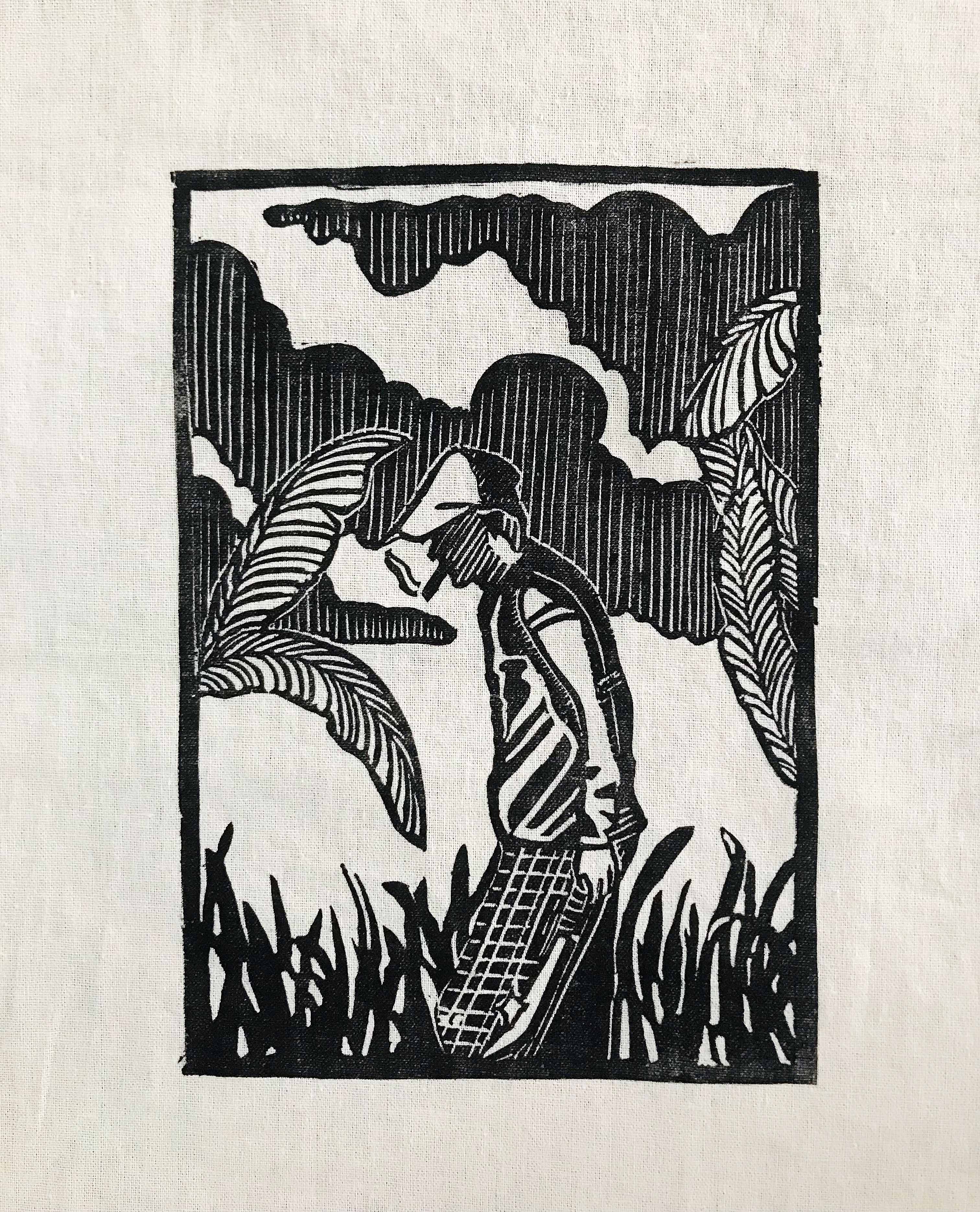

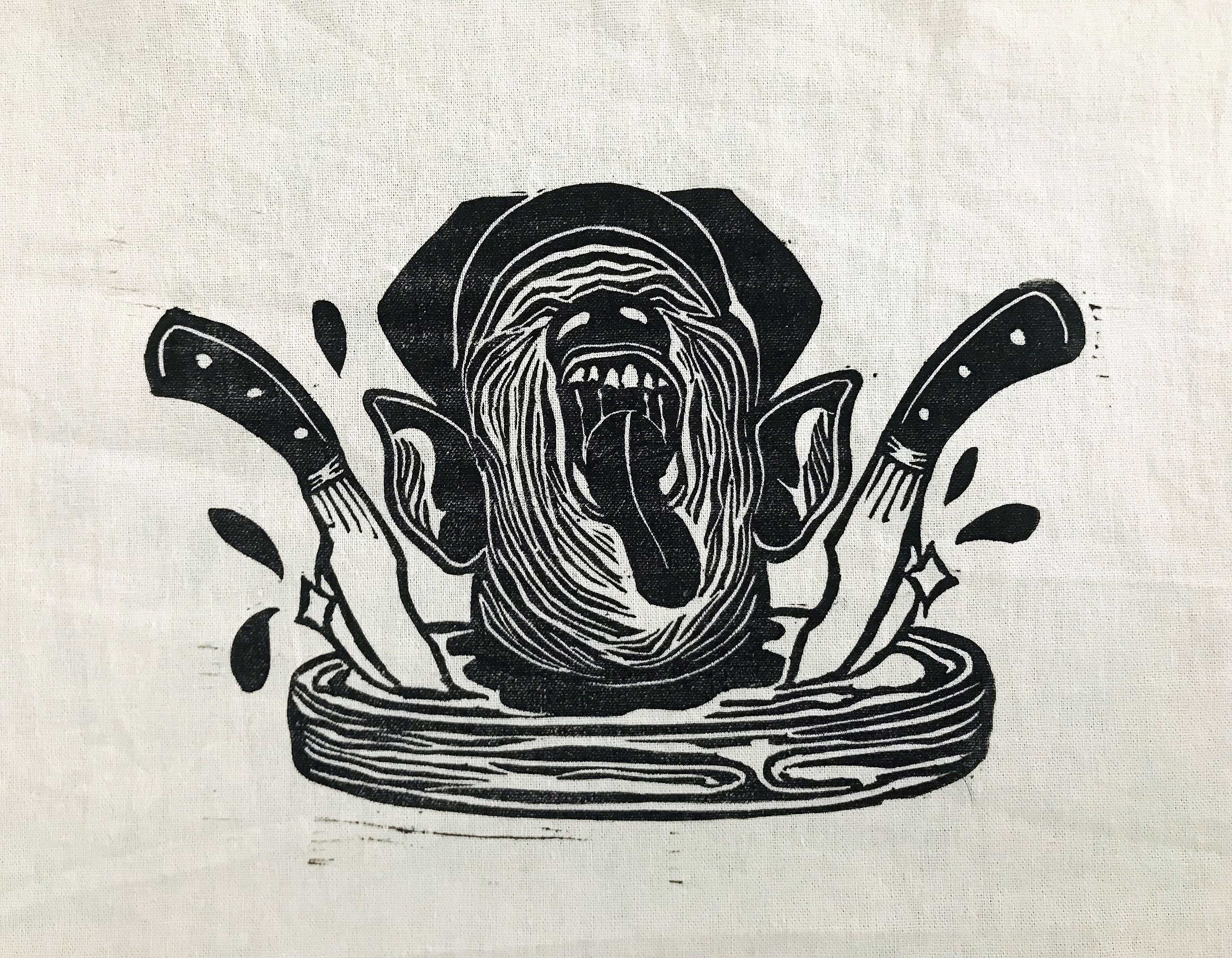

Working from a photo she took during a SAKA mass integration project, Palacio created Sa Lupang Kapdula. Being one of the targeted farm grounds for land-grabbing, the farmers in Lupang Kapdula, Dasmarinas, Cavite, face constant threats and harassment. As part of SAKA, Palacio spent some time living among them, learning their day-to-day work while gathering data on the community to see what more they can do to help and raise awareness about their situation. Berdugo sa Hapag presents a stark contrast in style and content. Inspired by the “ACAB” political slogan that gained resurgence worldwide around 2020, Palacio calls for a stop to their cruelty — the effects of which she has witnessed in Lupang Kapdula — in the image of a cop depicted as a pig whose head is served on a platter.

Similarly, Caubat’s Tagapagtaguyod ng Bungkalan is based on a photograph, this time of a sakada from Hacienda Luisita. The piece is a direct reference to the massacre of protesters which has not been brought to justice since 2004, and serves to remind us that the fight for basic rights and a greater commitment to national land reform continues for the farmers. Caubat sees this in the bungkalan movement. Bungkalan, or ‘tilling’, signifies the act of “producing enough for the community”, and is, at its core, a “reclamation and healing process” for many of the communities who have had to endure years and administrations defined by oppression and exploitation.

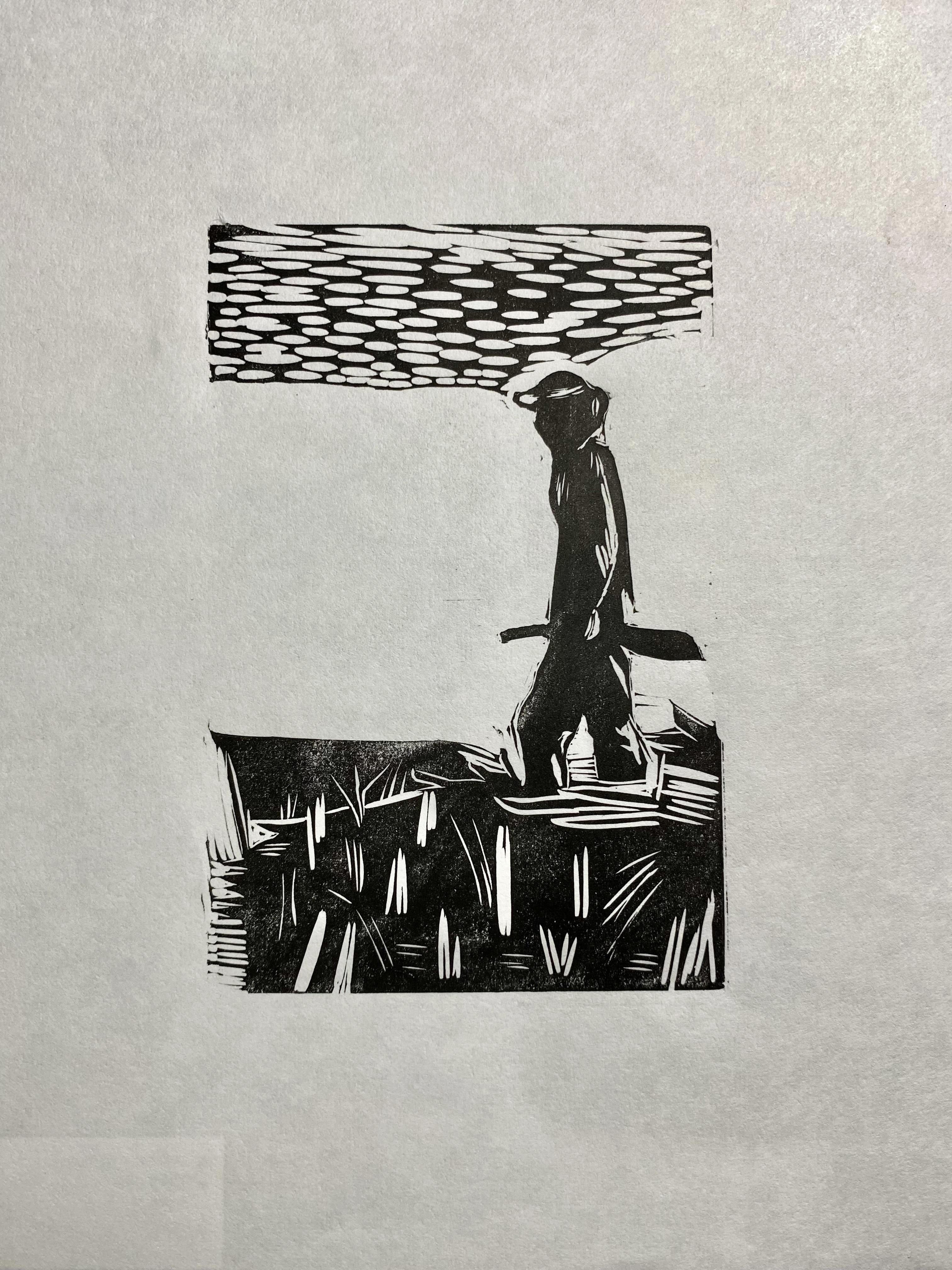

What began as a plate for a class, Rivera’s Sigaw then evolved into a “personal project”. The print, depicting an indivual “literally shouting for human rights”, pays tribute to the people who go out to the streets to protest injustices.

'Sigaw', Amiel Louise Rivera, 14 x 20 inches (2022). Left image courtesy of Amiel Louise Rivera.

Inspired by Estrelieta 'Ka Inday' Bagasbas, a militant leader for the urban poor community in San Roque, Villacorta's print Abante Babae celebrates the ten years since the residents of Sitio successfully barricaded and fought off the violent demolition of their community. Her other work, Pesante, was created originally for Sining Suporta para sa Kababaihang Magsasaka; she has also recently re-printed the work for a group exhibition with Artists for Anakpawis. Printed are the words 'Lupa', 'Hustisya', and 'Pagkain' — "our call for our farmers".

The history of the art of printmaking is also of great import to the collective, as Yang notes: “Printmaking stands at the front lines of progressive propaganda. It has long been an important part of Philippine activism. Along with other forms of visual arts, prints have helped expose the true conditions and progressive ideas of the Filipino masses, even way before the national democratic consciousness awoke in us as a people”.

That printmaking is a particularly expensive and widely inaccessible practice is a common issue the printmakers bring up when speaking about the difficulties they have encountered since starting their work. Palacio and Caubat, as full-time educators, sustain their practice with their day jobs but for a full-time activist Yang and student Rivera, printmaking spells compromises and creativity when it comes to just procuring materials. Rivera notes a particular dilemma printmakers like them are likely to encounter in the beginning: “I started printmaking in high school… and it’s not the easiest medium per se considering the costs, and as an activist, it’s really important for me to make things accessible”.

Villacorta sees these challenges as symptomatic of the country’s import-dependency. “I really want to print on textile but we don’t have any locally produced [textile ink for printmaking] here in the Philippines,” she says. If the government provided the right support, Villacorta believes such materials and tools could be manufactured and accessed locally, empowering artists and practitioners across all fields, like Professor Rey Concepcion of UP Diliman, who has been providing the printmaking community with his locally-made brayers (paint-rollers).

It is humble, simple living, but, as Yang emphasizes, thoroughly fulfilling. For her, as with the rest of the group, it is about “pagiging mahigit sa sarili” — to be part of something bigger than oneself.

Yang, commenting on the difficulty of finding affordable “proper” printmaking materials, says the practice has inspired a spirited sense of resourcefulness. With a can-do make-do approach to the art, she has been able to gather a rudimentary assortment of equipment, testifying to the accessibility of printmaking, while also drawing a symbolic parallel to one’s resilience and perseverance.

To the same effect, printmaking (unlike most other traditional art forms) is a physically taxing and time-consuming activity. While each member experiences exhaustion enough from their day-to-day activities besides their activism, energy and time is nevertheless spared for their art. “When you’re angry, all these emotions are channelled into the work,” Palacio relates. “Printmaking is a cathartic process — a coping mechanism in itself.” Printmaking can also be an outlet for improving mental health. Having struggled with her mental wellbeing throughout the pandemic through to the present day, Villacorta recounts how printmaking kept her uplifted and motivated to keep producing art, reminded by its effectiveness in "spreading information and awareness. especially among fellow artists".

For Rivera, for whom student-life has become an arduous balancing act, purpose and principle are fuel: “As a student who also works different jobs, the work given to us is often exhausting. I have my share of burnouts, but whenever this happens, I always try to take my time and think of why I started in the first place and for whom I am doing this for.”

While producing them can come with difficulties, whether physical, mental or even financial, prints themselves “effectively [reach] a vast number of people, being a medium that’s easy to reproduce, relatively affordable, and visually arresting.” The ease with which prints can be reproduced makes it an ideal medium for dissemination. This makes them easy protest materials to procure on short notice, while still being pieces of art — that is — immutable expressions of the human spirit.

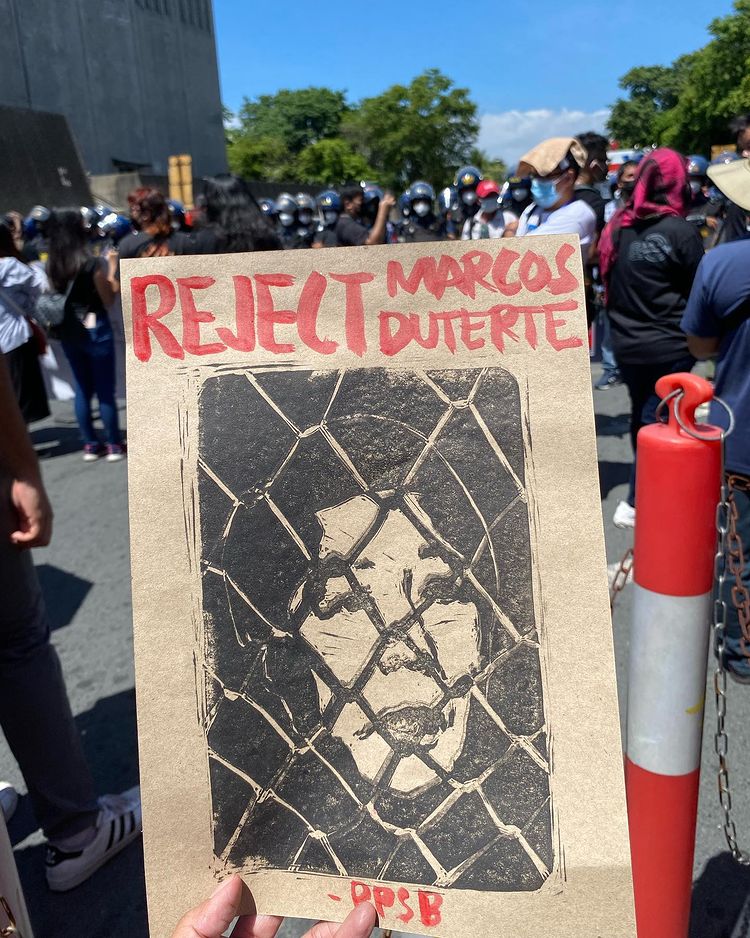

Since speaking to the members of PTP, a slew of alarming events has shaken the country, concerning, in particular, the community of artist-activists including the printmaking collective. Protesting the fraudulent win of the Marcos-Duterte tandem on May 25, protesters were met with violent resistance, reports Yang, who was part of the mass action’s organization and had, that morning, delivered AGHAM’s statement.[1] Members of the group expressed being “disturbed by the elections” (Joyce) and “still disoriented”, calling it an “attack to all sectors, all fronts”.

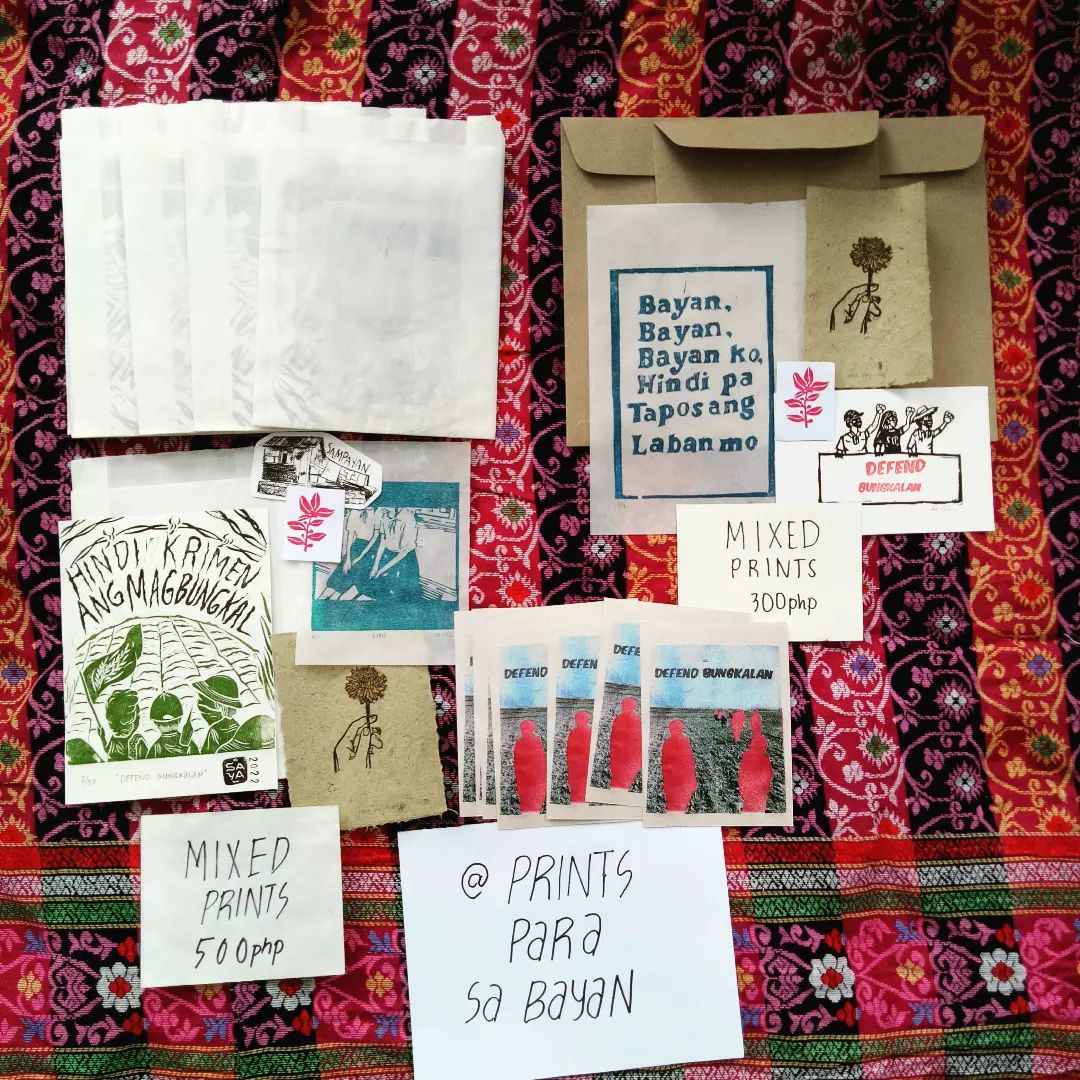

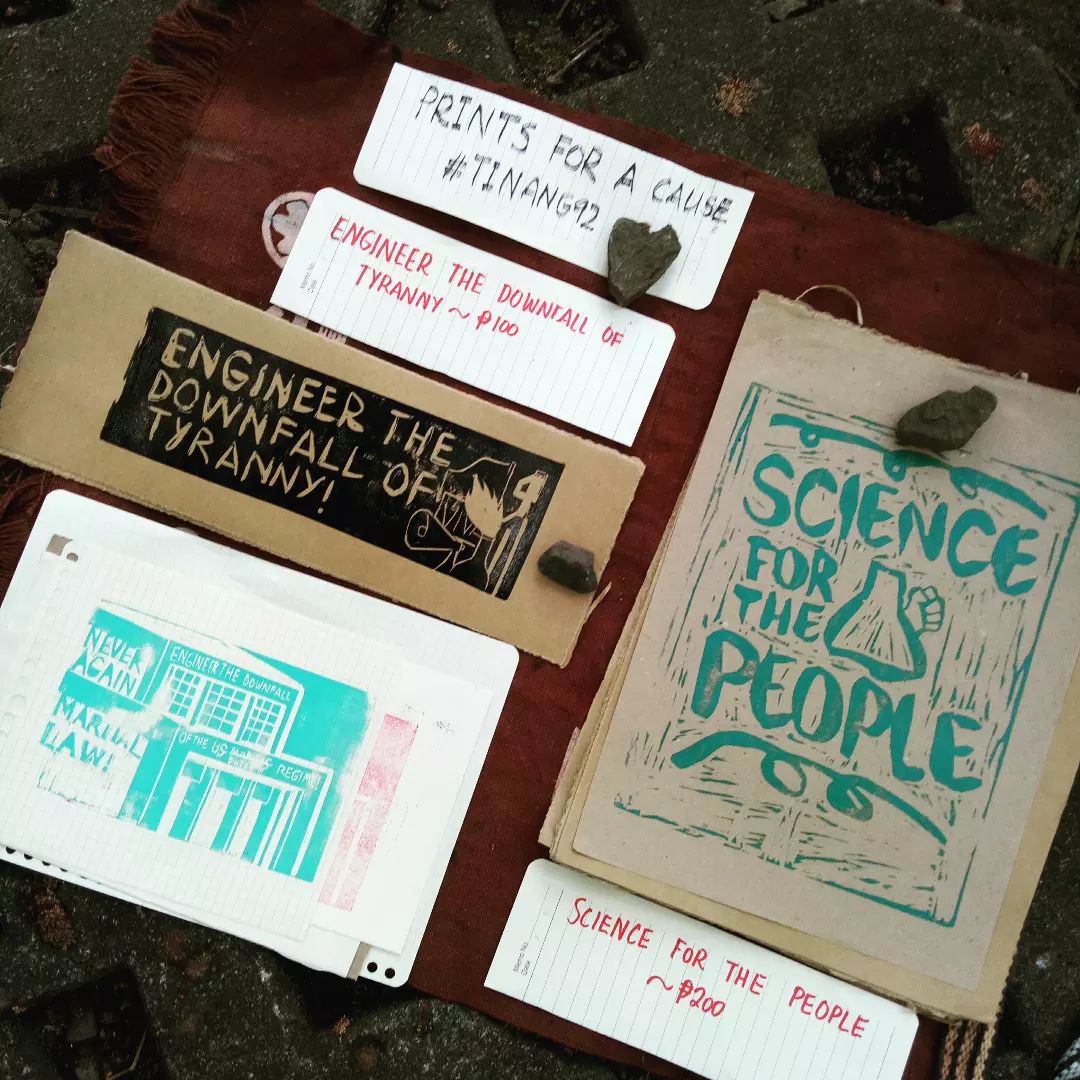

Not long after, farmers, artists and activists participating in bungkalan were put under arrest en masse in Tinang, Concepcion, Tarlac. Mass efforts to raise funds to post bail for the agriculture activists quickly followed. In support of these efforts, the printmakers participated in the June 12 'Picnic sa Bantayog' at the Bantayog ng mga Bayani grounds to sell their artworks.

Printmaking for the People/Prints para sa Bayan booth at the Picnic sa Bantayog. Images courtesy of PTP.

Reflecting on the precarious positions they find themselves as printmakers going against the grain of mainstream Filipino politics, they voiced mutual concerns with red-tagging, the malicious blacklisting of political dissidents that has increased in activity in recent years. However, for the members of the group, such efforts to dampen the voice of the people only fuel the fight. “What’s happened in the past regime will definitely happen again,” Palacio notes. “And things can get worse. But that’s not a reason for us to stop; if anything it’s a call to level up the work we do.”

To that, Caubat adds that “[the threat of being red-tagged] does not mean we have to cower, but rather continue to be more active and do what we have been planning to do.” As an educator as well as artist and activist, she stresses the importance of “[teaching] children to be more critical”, pointing out in particular the power of the arts in “[giving them] the chance to understand our social issues, and [giving] us the opportunity to mobilize”.

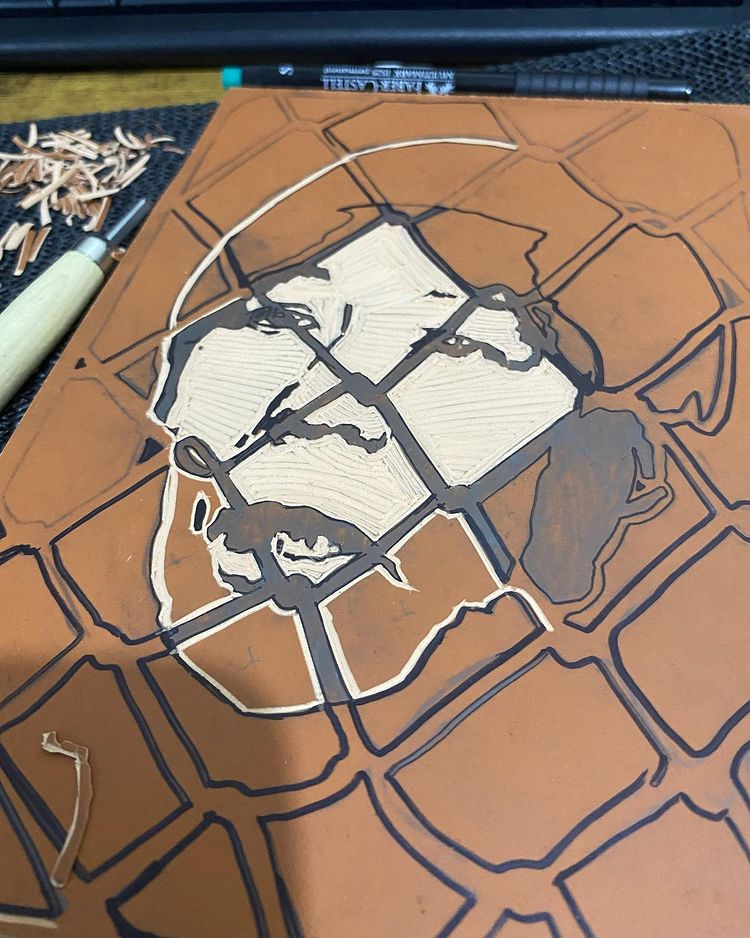

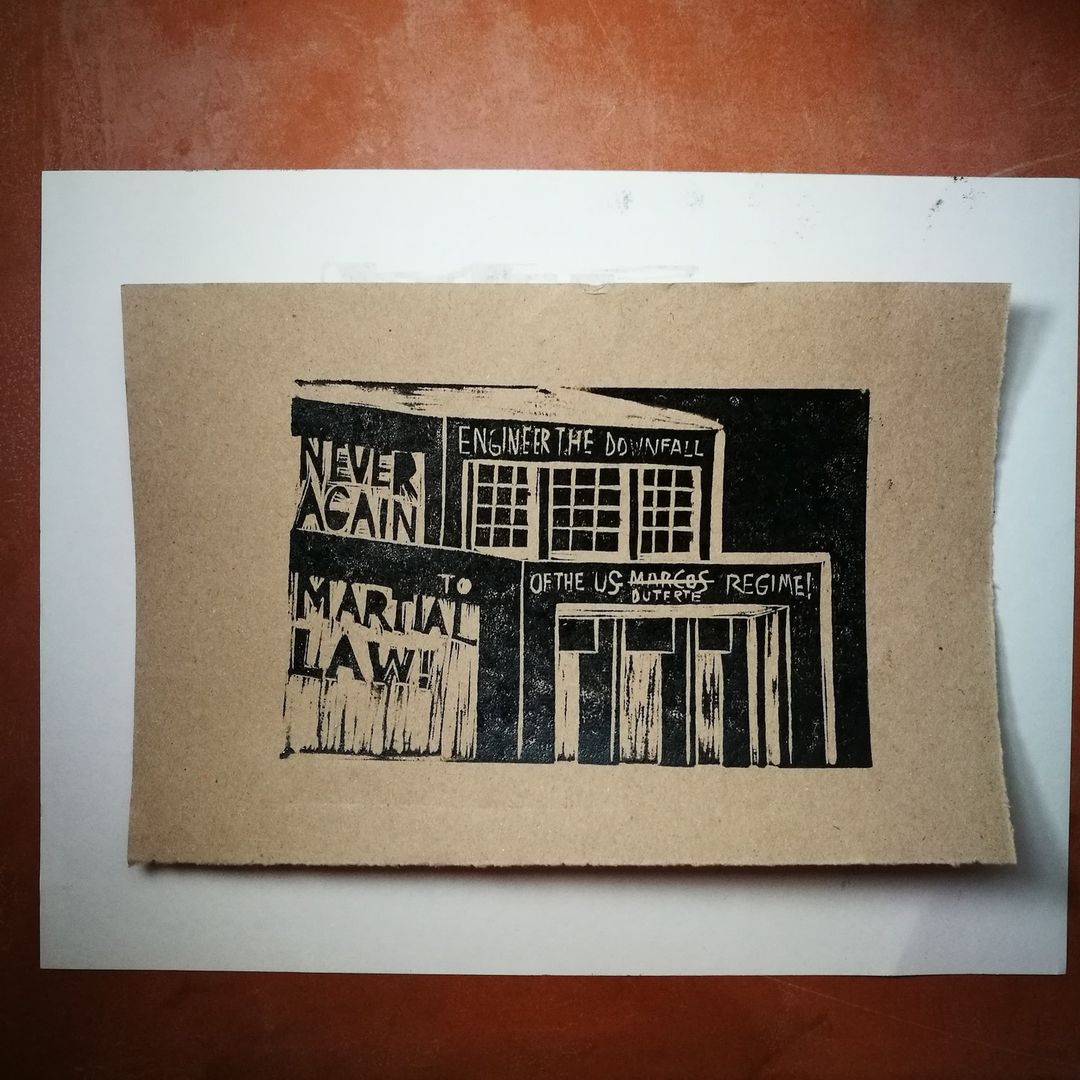

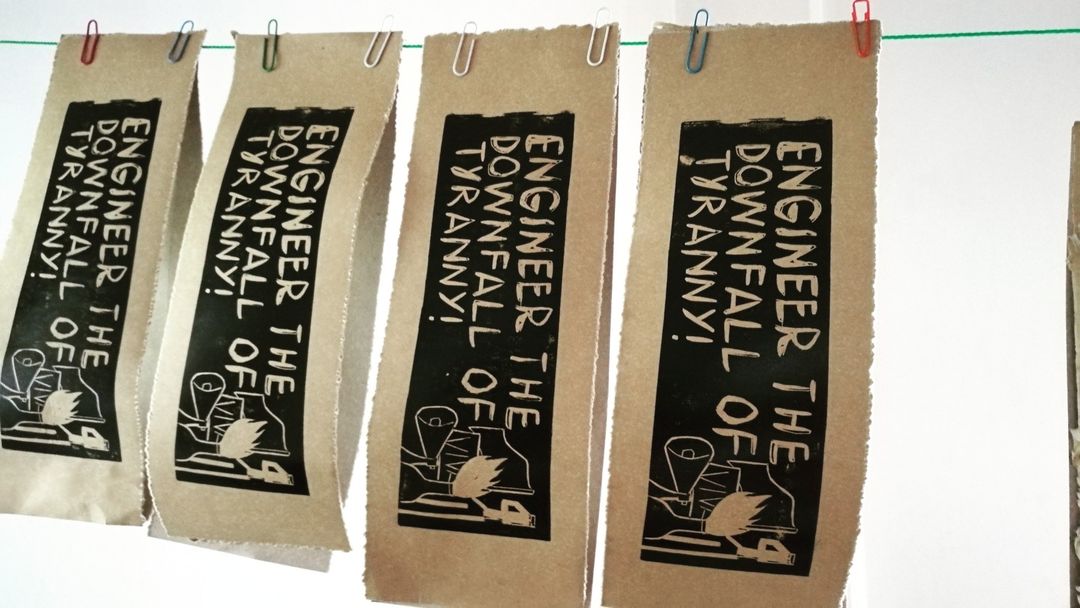

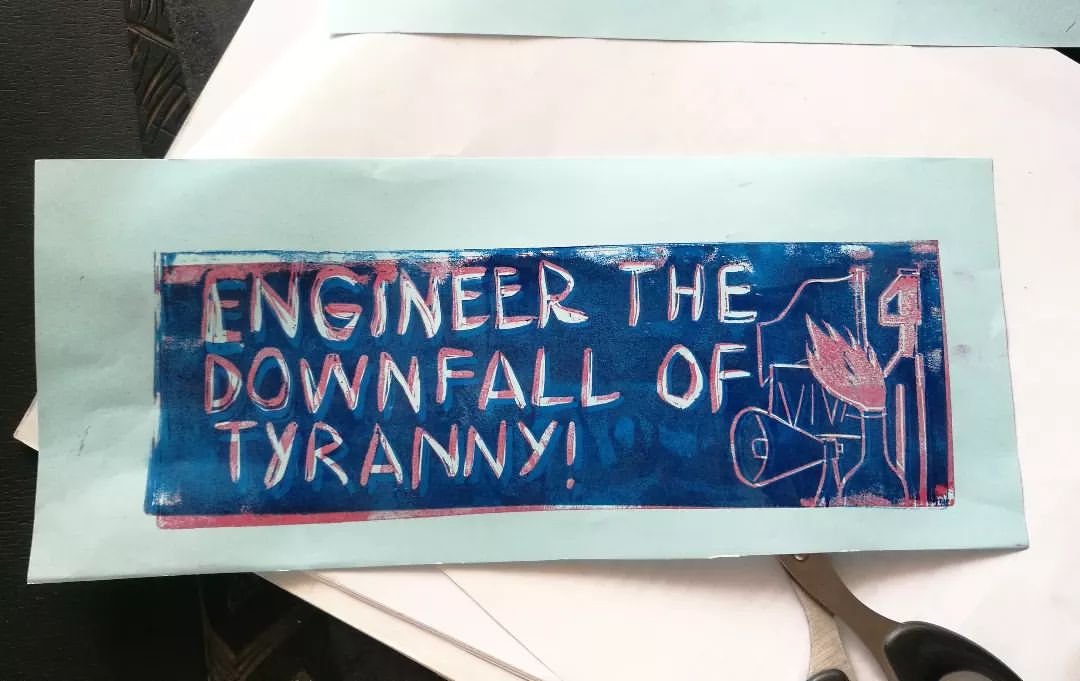

Collaborative work by Joyce Caubat and Saya Villacorta for PTP. Images courtesy of Joyce Caubat.

As several websites, news outlets and other online resources reportedly go down,[2][3][4] and the inauguration of a new Marcos creeps closer, the group ardently sounds the call for the people to stay alert, as Caubat reflected following the elections: “We don’t have to wait for another six years for good governance”. At a time when the future seems all too unclear, the printmakers stress the urgency of preserving the past and putting an end to historical distortion. Steadfast in their fight “to amplify the call of the people to stop the [Marcos-Duterte regime]”, the group moves forward with plans “to create learning materials for future community printmaking workshops” (Yang). More than ever before, Palacio states, we “need to persevere, fight misinformation and historical revisionism, and keep our awareness raised”.

Follow the activities of Printmakers for the People/Prints para sa Bayan on their official Facebook and Instagram pages, and personal accounts: Jona Yang (@minimumfare), Joyce Caubat (@neutropicalprints), Ina Palacio (@hellolinang), Amiel Louise Rivera (@alouiserivera), and Saya Villacorta (@sayavillacorta).

[1] “10 rallyists injured as cops disperse protest of Marcos proclamation”, Philstar Global, 25 May 2022.

[2] “Legitimate, progressive, or foreign-based: The websites Esperon sought to block in PH”, Rappler, 22 June 2022.

[3] “Government shuts off 26 websites”, Manila Standard, 23 June 2022.

[4] “Esperon has sites of news orgs, progressive groups blocked as 'communist affiliates’”, Philstar Global, 22 June 2022.