Pulilan, Bulacan, just an hour’s drive from Quezon City, Metro Manila, is an unassuming municipality surrounded by others that often get more limelight. But Pulilan has a number of aces up its sleeve.

The most apparent is its central bus terminal granting it easy access to and from Metro Manila and other major cities.

Next is the recurrent Pulilan Art Festival, which was paused due to the coronavirus pandemic. 2019 was its biggest year yet, seeing artists not just from Bulacan but from provinces from North and South Luzon, making the event arguably one of the bigger art forums outside Manila.

Finally, Pulilan has also managed to maintain much of its natural and agricultural health and heritage, and, in recent years surrounding the pandemic, this has taken extra import as more and more people become aware of the importance of how the two spheres contribute to human thriving.

At the height of lockdown, the town was able to weather the worst of the recession thanks to its locally-grown produce, heavily promoted and supported by the residents even before the pandemic.

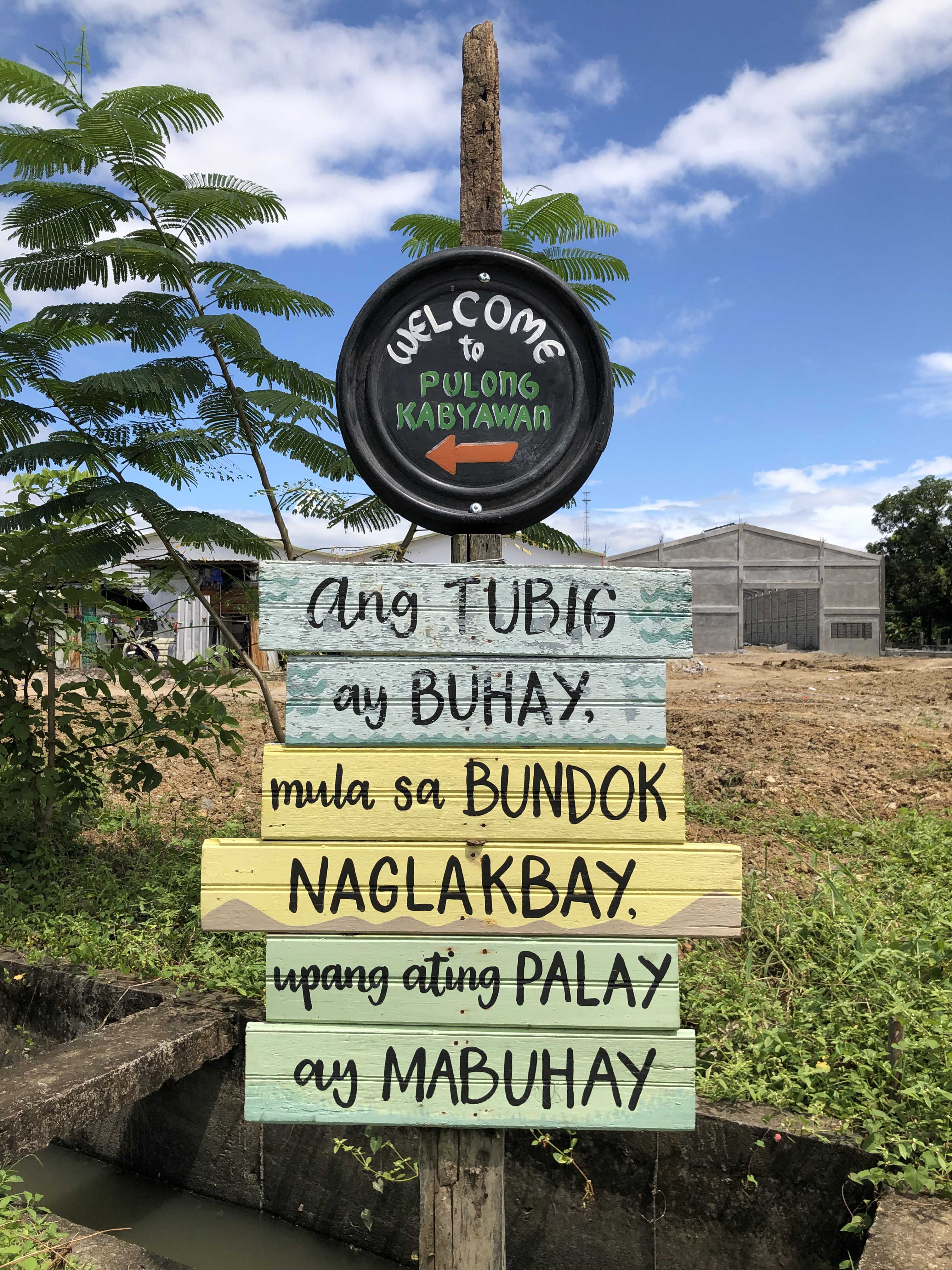

Given all these, Pulilan could arguably be a model city for sustainable living, and its latest community project, the Pulong Kabyawan (PK) ecotourism zone in Barangay Inaon, could be the crown jewel constellating all efforts towards art, culture, heritage, and nature celebration.

Green overgrows grey

We often hear stories about how farmers lose their lands to dubious notions of “progress” and “development.” For Filipinos in this era, it’s become something to expect at this point, but it doesn’t make each time hearing it less painful.

In such a sea of literal and figurative grey, the emerging success of Pulilan’s projects stands out as a literal and figurative oasis of green.

Sitting on twenty hectares of farmland, PK is a series of homesteads that was declared a protected zone after residents, led by Andrew Alto de Guzman, organized to appeal in light of encroaching industrialization. The tour site proper consists of seven hectares within the protected zone, on land owned by Alto de Guzman’s family. “Ang buhay ay bukid, (Life is a meadow,)” goes Alto de Guzman’s motto.

Within sight of the zone are a series of bodegas standing on what used to be agricultural land. Despite this, Alto de Guzman and the residents aren’t worried as laws were passed forbidding industries that damage soil health, thus, despite the rest of the area being industrial, they can only build warehouses.

Additionally, the project is also one good example of a nascent paradigm in the tourism sector called community-based tourism. As the name suggests, this model brings agency back to the community, where traditionally, outside businesses mainly profit from setting up shop in a locale, sometimes at the expense of locals.

This model best shines when the community members know fully what’s at stake and receive the proper training and frameworks that would otherwise come from outside.

In PK, it was mutual. While Alto de Guzman and the other cultural workers provided the frameworks to run a sustainable business, the farmers themselves drew from their knowledge of the land to run an engaging ecotour.

Presently, PK offers interactive farm tours where visitors can participate in the activities farmers do, depending on the season: planting or harvesting. Open only on weekends as the area is a fully-functioning farm on weekdays, people can also just visit to lounge and relax in the many casitas.

There’s also a cafe serving locally-grown and produced food featuring unique Pulawenyo spins on Central Luzon cuisine. Finally, there’s also the Museo Pulong Kabyawan featuring Bulacan and Pampanga artists, as well as a pictorial and tactile history of the farm and life on it. For those planning to stay longer, there are pool resorts within the zone.

Museo Pulong Kabwayan.

True wealth

It wasn’t easy, getting PK off, or rather, on the ground. But Alto de Guzman has had much experience working with his fellow Pulawenyos in organizing worthy projects.

“Gumawa ng kakampi imbes na kaaway, (Make friends instead of enemies,)” de Guzman tells me as we drive to PK from the Pulilan central bus terminal.

Many advocates of initiatives aimed at protecting different kinds of heritage and marginalized sectors are understandably very critical of certain institutions, but Alto de Guzman reveals that his approach to conflict is what helped many projects materialize, and more importantly, receive sustained support.

The first set of doubters he had to convince—and convert—were his family, particularly his mother. “Na-convince ko na ang family na ibalato na natin ‘to sa next generation,” he shares, gazing out from under the heritage kubo, “huwag na nating ibenta. (I convinced my family to give the land to the next generation, to not sell the land.)”

He cites that the bodegas surrounding PK are built on agricultural land sold by former residents. Other residents eventually got pinned between warehouses, and had to sell their lots and move out, too. “When I introduced farm tourism,” Alto de Guzman muses, “parang nagkaroon ng hope. (Hope was given.)”

Pulong Kabyawan transliterates to “Island of Carabao Mills” and I ask Alto de Guzman if the zone is an “island” in a “sea of grey.” “Plan B ‘yun,” he admits, if all else fails, the seven hectares belonging to his family might be the last bastion of bukid here in Inaon.

But he and those with him are hopeful. There’s a family renting one of the casitas. The children play under the trees, the adults, some of them on hammocks, trade laughter and remembrances.

Pulawenyos considered these groups as nuisances, but since the first festival more than a decade ago, homeowners now clamor for their walls to get decked with mural art. He mentions that past city administrations also doubted him and his groups, but he was eventually able to win them over to support initiatives like the construction of museums.

Before PK, in 2015, Alto de Guzman already convinced his family to return to cultivating the land, and so they began growing red and brown rice now served at the PK cafe. He cites that all-too-familiar case among Filipino siblings where conflicts arising over property inheritance stain relationships.

“Of course, I also have to show my family that it’s [a] sustainable [venture]. Remember, napaka-mahal na ng property na’to dahil tagged na as industrial. Nakikita mo ‘yung tukso, ‘di ba? (Remember, the property is valued at a very high price as it’s tagged as industrial. You can see the temptation, right?)”

His nephew also works in PK, in the cafe, and Alto de Guzman believes that this will get him to experience, not just hear about, what’s at stake. The uncle plans to eventually transfer ownership of PK proper from his family to a foundation.

Alto de Guzman seems very relaxed as we talk under PK’s groves, but later, on the drive back to the Pulilan central terminal, I find out that he works six days a week. A business graduate, his main income source is a construction company which he runs. He only takes ethical commissions—no expropriated land, follow all codes—and at times too, the government contracts him to restore heritage structures. He shares that it doesn’t end there, however, and that aside from livelihood, his job allows him to work on his art and advocacies.

Alto de Guzman and I cover many topics—socio-civic organizing, art and politics, the intangible lessons from farm life which have tangible impacts on other aspects of life, but we often circle back to what this man of many hats describes as “the mission.”

Installation shots from Museo Pulong Kabwayan.

A man on a mission

It started in 1986, when Martial Law was lifted. Pretty soon, the young Alto de Guzman, with friends like then-young friends Reuben Cañete and Roland Cruz, started organizing and pitching proposals to their local governments and rotary clubs to help them initiate heritage conservation projects, including the establishment of museums in Pulilan.

If he had a choice, he’d rather always be painting or sculpting, but he’s not one who believes in “art for art’s sake alone.”

“Marcel DuChamp, Ai Weiwei, ang Guernica ni Picasso, anlalakas niyan!” He riffs, as we cut through locally-produced longganisa, “the Spoliarium of Juan Luna, nauna pa sa Noli, sa pagtatayo ng Katipunan! Nag-encourage siya sa Pilipino na, “uy, pwede tayo maging superior sa kolonya na ito, at pwede tayo kilalanin sa buong mundo! That’s the power of art.”

(“Works by DuChamp, Weiwei, Picasso are powerful! Luna’s Spoilarium came before Rizal’s novel the Noli, before the Katipunan was founded! The painting encouraged Filipinos to see, hey, we can be better than our colonizers, the world can recognize us. That’s the power of art.”)

He considers one’s work as a “life extension,” clarifying that “wala ka na sa mundo, pero ang sining mo, andiyan pa rin, nagtuturo, nagbubulat, nag-e-encourage, nagpapa-laya, nagpapa-himagsik. So napaka-halaga ang pagiging totoo sa iyong trabaho.” (“You’re no longer in the world, but your art remains, teaching, opening minds, encouraging, freeing, revolutionizing. It’s very important to be true to your work.)

Perhaps he’s not just referring to art.

As previously revealed, relationship-building is an art form too, especially winning doubters over, and one that not only starts at home, but comes home as well.

I see Alto de Guzman’s widest smile yet, as he reveals: “Mommy ko, nag-85 na. Five years ago, kontra siya dito. Sabi niya, “andiyan na mga pabrika, ampangit na.” Sabi ko, “mi, give me five years. We will celebrate your 85th here.” Alam mo, bago siya mag-85, in love na in love na siya sa lugar na’to!”

(“My mom recently turned 85. Five years ago, she was against my plans for our land. She said, “the factories are here now, spoiling everything.” I told her, “Mom, give me five years. We will celebrate your 85th here. You know, before she turned 85, she was so in love with this place!”)

For inquiries, message 0969 231 1864 or email pulongkabyawan@gmail.com. Follow Pulong Kabyawan on Facebook for updates.

When Pao isn't writing about art, he's trying to be a cat-whisperer.

Images courtesy of the artist and Pulong Kabyawan.