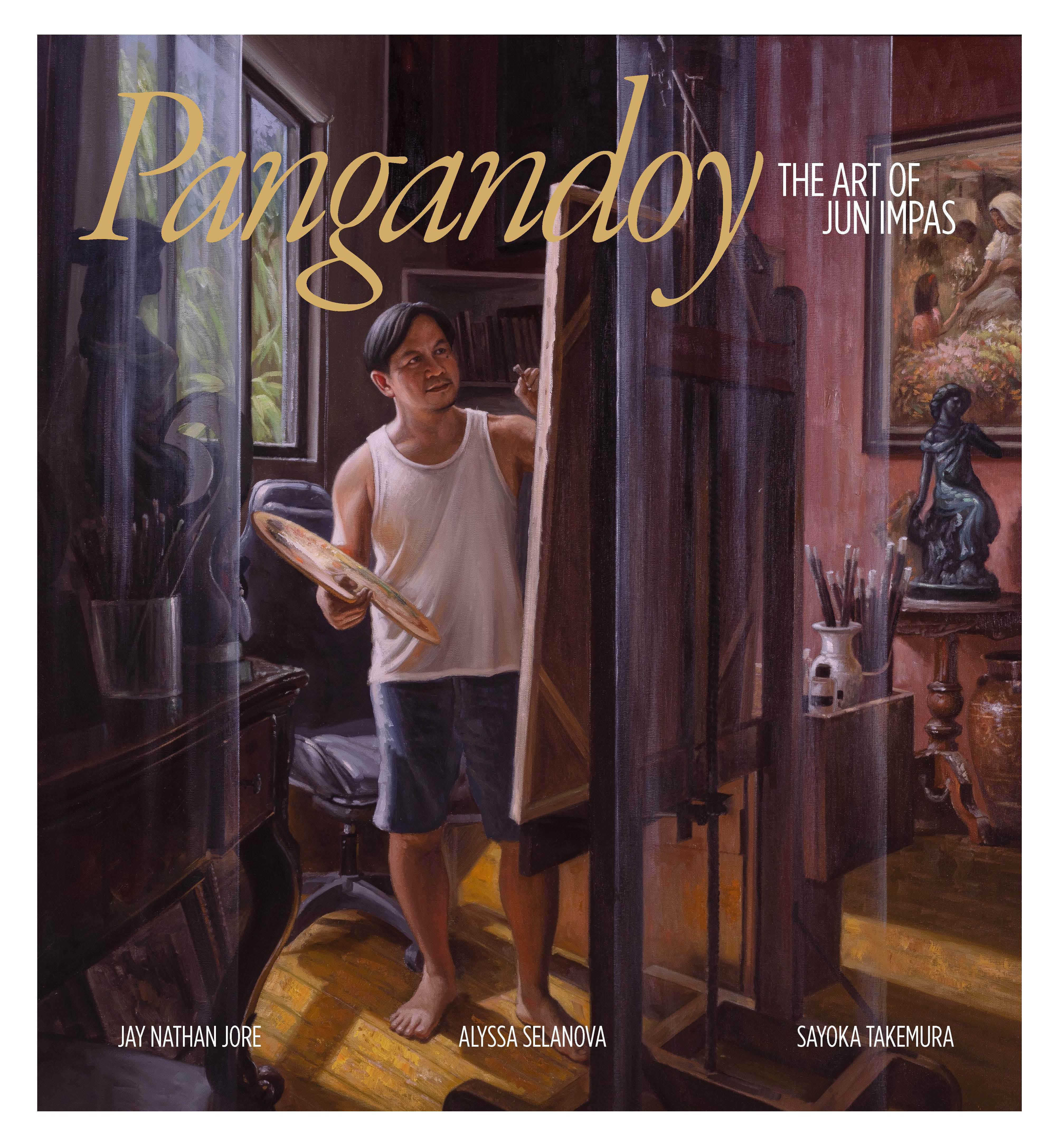

The life and work of Visayan realist painter Florentino “Jun” Impas is the subject of a recently released monograph, Pangandoy: The Art of Jun Impas. Essays by Cebuano art writers Jay Jore, Alyssa Selanova, and Sayoka Takemura appear in the book and chronicle the struggles and victories of an artist whose socio-economic background was no barrier in following his dreams. Loosely translated to yearnings and dreams, Pangandoy is also the title of Impas’ first solo exhibition at the Montebello Villa Hotel in 1998. Twenty-five years later, the artist earned his position as one of the most recognized figures of “Sugbuanon Realism”, a term used by critic and art historian Prof. Raymund Fernandez to describe practices that descend from traditional and academic painting as exemplified by generations of artists documenting reality through landscapes, portraits, and unembellished depictions of life.

From billboards to the canvas

Born in Danao, a town known for its gun industry and the long pristine shoreline visible from the national highway, Impas’ family relocated to Surigao, where he started drawing and sketching with his older brother, Dodong. Later, the two found jobs hand-painting billboards for movie theaters in an era that precedes the digital graphic design industry. In his 20s, Impas decided to move to Cebu City and commenced employment in a print business. There, he would make signages and screen print hundreds of t-shirts. With an entrepreneur mindset, Impas would eventually set up his own shop. Once everything in his enterprise settled, he renewed his commitment to art by painting every day and completing a body of work that had become the center of his show at the Montebello. To his surprise, patrons became interested in his work, which led to his decision to become a full-time artist, as he was guaranteed an alternative source of income through commissions and the steady support of his early patrons. Soon enough, his paintings became at the forefront of exhibitions across the country, particularly in Manila, where a concentration of art galleries and art spaces are found.

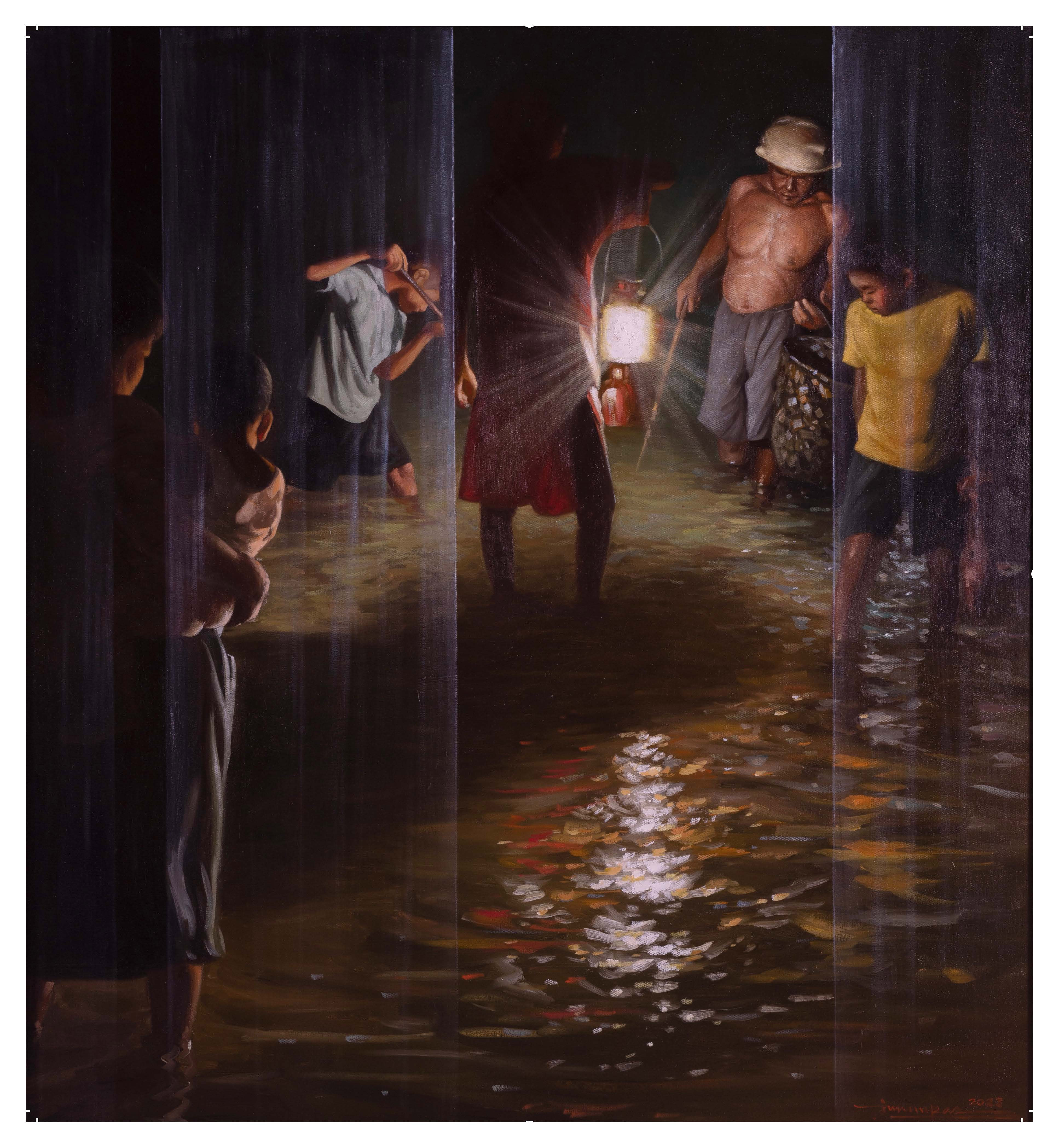

In the decades defining his career, Impas painted dozens of pictures from ordinary life: scenes from the regions as the artist records different approaches to living as a Filipino. From festivals to the stillness of a normal weekday, his paintings orient us to see the peripheries. Perhaps, this is the motivation for artists in the regions to continue with the tradition of realism and figuration: to make themselves seen and emerge from the shadows of the domineering hold of the capital to the narratives about this country. Selanova writes, “Despite being isolated from art capitals, Filipino artists’ works were marked by a genuine naturalistic representation rather than purely painterly concerns or conceptual innovations. Their isolation allowed them to engage in pure creation, leading to the development of a unique Filipino character in their art defined by subjective emotion, simplicity of vision, clarity, and solidity.”

A look inside Bisaya Realism

Divided into five chapters, the 234-page book offers a thorough survey of Impas’ ouvré and, by extension, whilst singular in perspective, the evolution of image-making in what Jore calls “Contemporary Bisaya Realism”, which was adapted from Fernandez’s more specific classification of generations of Cebuano artists following the paths of masters such as Fernando Amorsolo, Martino Abellana, and Romulo Galicano. However, Jore argues that the movement does not simply draw from tradition but “rather follows a particular way of looking and relating to the artwork’s subject as it corresponds to reality”. He adds, “style becomes only a metaphor that captures the aura of things as they are being gazed upon by the painter.” and cites the case of Abellana as his “use of impressionist brushwork, at times exuding rather expressionistic and abstractive energy does not limit the Bisaya painter to the techniques of academism that were taught in formal art schools.” Jore continues, “Contemporary Bisaya Realism then is about the artist’s reliance on his or her ability to mediate the nuance of reality on the surface of the canvas. It is a dedicated and committed gazing of reality, highly focused on capturing the essence of form and the aura of its appearance despite the temptation to idealize, abstract, or simplify. It is an insistence and stubbornness to record reality as it appears before one’s eyes.” While Impas shares this inherited perspective of Bisaya Realism, he worked on his techniques and claimed his compelling approach to naturalism learned through experience and perseverance. As a struggling painter with limited access to the works of the masters, Impas did his due diligence by studying the works of his predecessors through books and other formats. One of which is a dilapidated calendar that contains enthralling images of Jose Kimsoy Yap’s paintings of heritage churches; they feature colonial structures rendered with a palette guided by the interaction of light and shadow as the buildings rest in the middle of the tropics—a technique that seems to be visible in Impas’ translation of images onto the canvas.

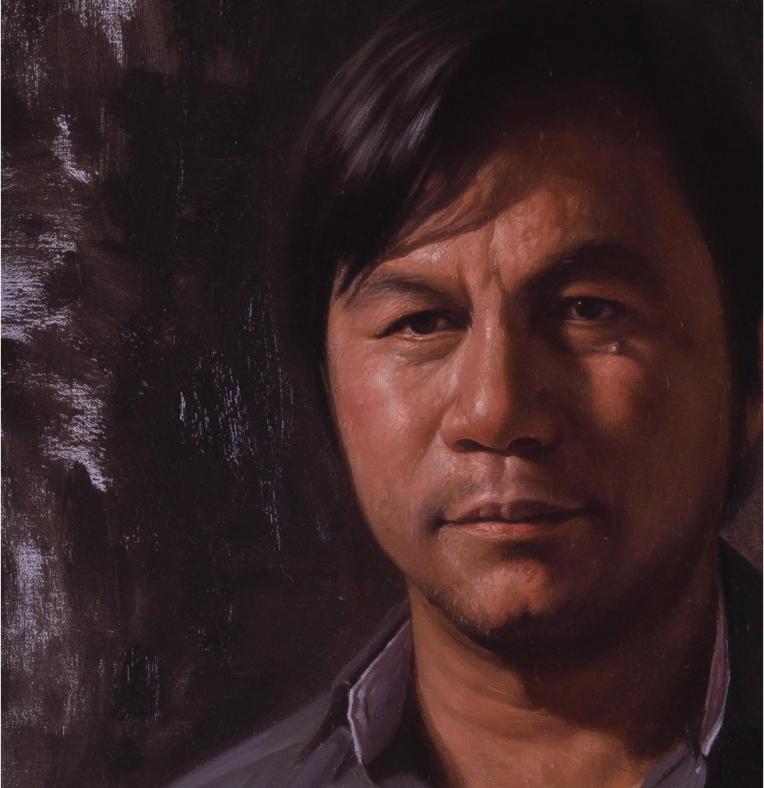

Meanwhile, in the chapter describing Impas’ practice of portraiture, Takemura notes that “In his body of work is the imposing, either dressed quite severely or bedecked with fanciful ornamentation; the relaxed faces and postures of some in casual wear; and the quiet allure of the few who need no glitter or formal introduction yet command attention through their unassuming presence.” From the most influential families across the country to members of the clergy and the common man, Impas had made portraits that decoded the stature and life of his subjects, Takemura assesses, “From the pressed edges and seams and the billowed spaces between the snug fit of cuffs and collar, the artist’s strong understanding and execution of color and lines informed by their interaction with the light source to create the illusion of form and volume achieves this. Though, beyond merely adeptly replicating what meets the eyes, the almost palpable accuracy of Impas also paints a glimpse of who the person is (or, in other paintings, who the people are): their demeanor and advocacy and what guides their direction…"

Florentino’s and Legacy

Accompanying the book is an exhibition of the artist’s seminal works at Florentino’s, an art space established by the Impas family located in the hilly neighborhood of Balamban, a 30-minute drive from the city. Overlooking hills and mountains, the estate had turned from a simple vacation property to an art space promoting eco-tourism and generations of young artists honed through initiatives led by the artist and with the Alliance of Two Hearts organization. Impas plans to host artist residency programs and exhibitions.

Pangandoy is the inaugural publication of the Cebu-based BAMBOOVILLAGE. A recently founded independent press, it intends to document the creative practices and endeavors of individuals, collectives, and institutions across different fields. From monographs, zines, and other experimental forms, the publishing house is interested in projects that highlight (but are not limited to) arts and culture, mainly in the Visayas region while merging local and global contexts.

For inquiries on the book, you may contact BAMBOOVILLAGE at info@bamboovillagepublishing.com or +639498804797

Images courtesy of BAMBOOVILLAGE Publishing unless otherwise stated.