Amid Manila’s haze, a neon sign flashes two words in orange cursive: Everything’s Fine. Equal parts starry-eyed affirmation and clenched-jaw rebuttal, ‘everything’s fine’ is the mantra of our volatile times defined by well-intentioned pessimism.

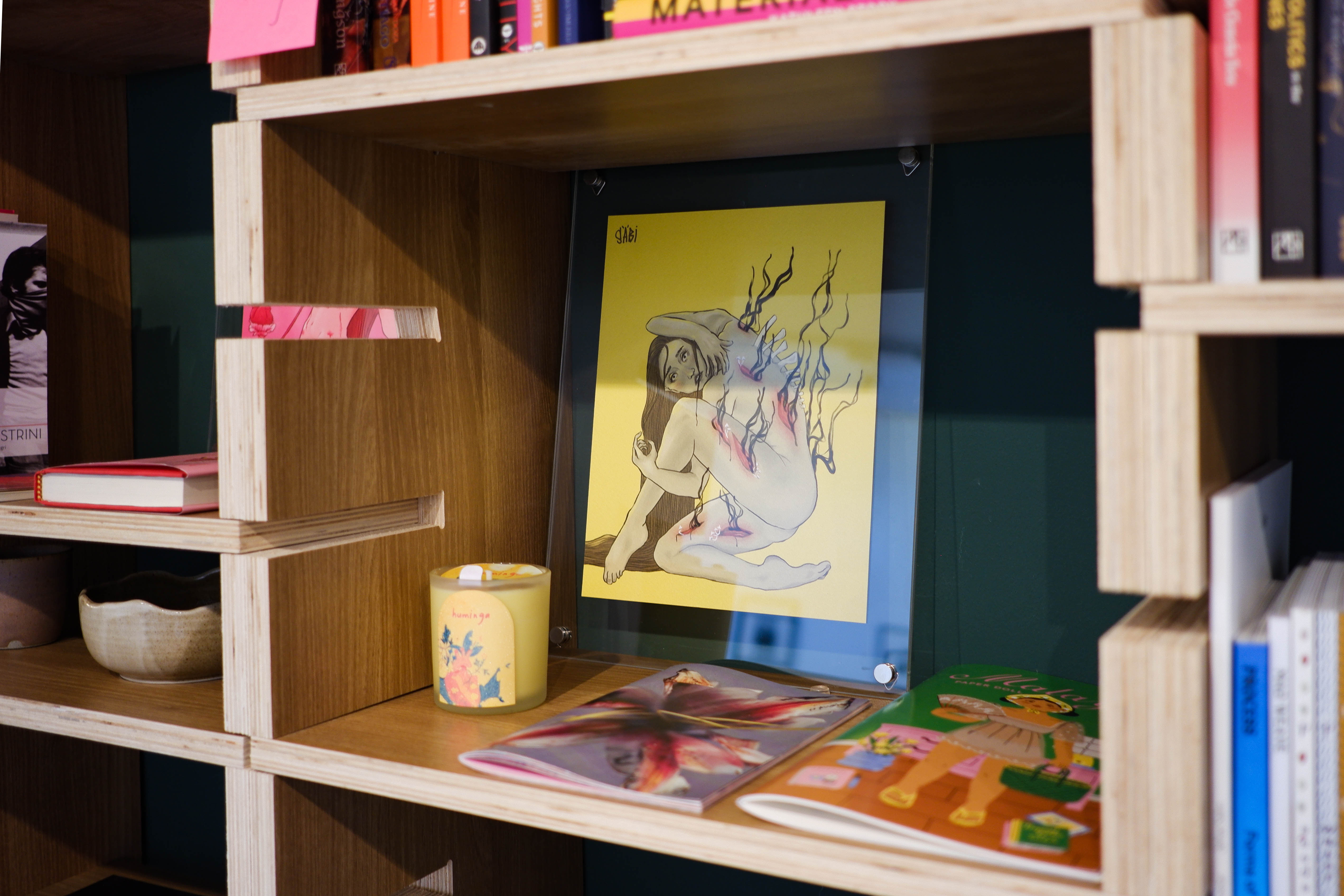

Upon closer inspection, I notice that the sign sits behind glass, revealing the inside of a quadrangle room. On one wall, twelve photographs are spaced out in a meditative rhythm. On another wall, floor-to-ceiling shelves carry rows of books, a few houseplants, and framed prints.

Helmed by designer-poet Oliver Ortega and writer-art critic Katrina Stuart Santiago, Everything’s Fine is an independent bookstore and gallery, and small press. Their inventory includes paperbacks from independent and commercial publishers, editioned artist books, and artworks. But, what defines Everything’s Fine is Ortega and Stuart Santiago’s commitment to transparent and collaborative practices in the cultural and publishing sectors.

When I sit down with Stuart Santiago in Everything’s Fine for this interview, the Palanca-winning writer recounts her path from writing art criticism to running a bookstore and how artist books can be a part of one’s life. Most importantly, Stuart Santigo shares some wisdom on how to engage with difficult topics through art.

MOT:

Can you tell us a little bit about Everything’s Fine?

KSS:

Everything’s Fine is a small press I co-founded with Oliver Ortega. We’ve known each other for a long time through independent bookmaking and art scenes. I was an art critic and Oliver worked with galleries around the same stretch that I was writing about art. We moved around the same circles in the literary and art worlds.

We worked on Ishmael Bernal’s Pro Bernal Anti Bio, which was co-published with the friends of Bernal and ABS-CBN Publishing. When we collaborated on that—he as the designer and I as a producer of the book—we realized we wanted to do the same things. We wanted to make the same books and we liked the same authors. But also, we wanted to see if there was a model we could try for bookmaking, publishing, and writing that was more fair for those involved.

We both come from the independent and marginal self-publishing space. We wanted to find a halfway point between that and mainstream publishing. For us, it’s really about fairness and transparency among everyone who makes a book happen.

When we decided to do the bookshop, the space came to us. Oliver was just walking down the street and found it. He was just walking through the park because he lives nearby. The person in charge of renting out the place wasn’t even responding to anyone at all for four months. But, when we called, he answered the phone.

I’m a big fan of signs.

MOT:

Speaking of transitions, what was the shift like from being a writer to being an entrepreneur for you?

KSS:

I’ve always been an independent writer. I’ve never been hired full-time to write by any company. I stayed with the Philippine Daily Inquirer as a freelancer for about two years. Then, I was with GMA News online for about five years just doing the arts and culture beat.

I knew I was dispensable. The entrepreneurial skills have to kick in if you’re a freelancer. You’re always kind of selling yourself to get the next gig.

I’m also very clear about the fact that I have the privilege of being a freelancer. When I was writing freelance full-time and finding my footing, I lived with my parents. That privilege, I’d like to think, I used well because it strengthened my sense of what independence means—and what it doesn’t.

Independence is something I carry over from being a writer and publisher. I don’t know if I’m the entrepreneur concerning the paperwork and the numbers—that’s mostly Oliver. But, that independence allows you to imagine things to be better. You don’t need to fit into the box of what an entrepreneur or small business owner is. We’re able to change the rules and remove rules that don’t work.

We were very lucky that we have Koki with us because he worked in the gallery system for a long time, too. He’s familiar with my work as a critic and, obviously, familiar with Oliver because they worked together before. So, Koki kind of balances us both out because he’s more exposed to younger artists. He also has an independent streak, so he contributes his own thing to the press and the bookshop. Certainly makes the gallery work a lot easier for Oliver and myself.

Jerry is our pop-up kween and bookshop fairy who can make you buy a book you didn’t know you needed, and Erika is really an all-around creative who does graphic and book design, photography and writing, too. As the two people that spend the most time in the shop, they’ve had the initiative to build systems around how to run the shop, which we appreciate. They both know me as a writer and person, and so they kind of make this shift to being a business person easier for me. Growing more familiar with the people we work with makes things easier. That all of them—Koki, Erika, and Jerry—also believe in the vision of Everything’s Fine is of course most important.

I think these shifts just happened. I never thought I’d be a publisher of other people’s books. I thought I’d just always be publishing my mom’s books and my books. We had friends and writers who were so willing to give us their work for publication, which I thought was a sign that this could happen.

MOT:

Everything’s Fine carries titles from independent and mainstream publishers alike, like Exploding Galaxies and HarperCollins. Your inventory is eclectic, but I can sense a strong curatorial hand across everything in this store. What’s your philosophy on deciding whether or not to put a book on your shelves?

KSS:

First and foremost, It needs to be a book that we like. A book is here because someone recommended that book, and that’s usually one of the five of us at Everything’s Fine. We knew from the start we needed to curate the books heavily given the limited space and the fact that we wanted to have a gallery. In the beginning, we thought “Okay, maybe that’s going to be difficult.” But now this curation has become second nature to all of us.

So many months in, we have a better sense of our audience. We curate by feel, but also deliberately, for habitual readers. You know, people who will pick up a book at the end of the week, or every suweldo. People who want to try a new title, an unknown author, or an art book. I think we’ll forever get every weird book we encounter and always hope and pray that there’s a reader who will be as interested in it as we are.

We’ve always wanted to champion independent and small presses, especially from the Philippines and Southeast Asia. I was very lucky because I also have a solid network of Southeast Asian friends, scholars, and creatives. A lot of the titles that we carried from the start, I had brought in from my travels elsewhere. I was in Europe for the International Federation of Arts Councils and Culture Agencies (IFACCA) conference earlier in the year, so I brought books from there. I was in Kuala Lumpur for the Southeast Asian Art Censorship Database Launch and I brought books from there. Oliver flew to Germany for the Frankfurt Bookfair, so many of these current titles come from there.

I think the key is to do things thoughtfully and deliberately, which is the beauty of being small: you can take time, you can decide what is most important.

MOT:

With Everything’s Fine, you’re creating a community through curation and this space. What’s the decision-making process like for the gallery? What makes you decide to carry artwork here?

KSS:

We knew that there were a lot of projects that had to do with our exposure to the art scene and artist collectives and communities. We knew that we wanted the space to host artists’ activities.

In terms of curation, the programming for this year was very loose because we were just opening. We didn’t know the workload yet. We were sure that we wanted to exhibit Pam Zeta and The Demo Versions of Aldus Santos. So, this was planned. We knew that we wanted to open with JL Javier and Apa Agbayani’s Tenderness because we brought the printed matter to the Singapore Art Book Fair earlier in the year.

I personally loved Tenderness because of how it used photography to make public such private moments, and yet let these unfold in a book that only captures a few of the photographs, almost like a story that can continue unfolding. I continue to be awed by how JL’s camera caught emotions through the body, and how it reminds me of how the making of a photograph might have a lot to do with intimacy and a sense of knowing. That it was so heavily grounded in Apa’s words about masculinity, and contextualized in a time when we were culturally being changed by its toxicity makes the work even more important.

I think that one of the worst things we do is that we evade difficult conversations in this country, especially when it’s about art and artmaking. We want to have these conversations around fairness and justice in relation to art, but also in terms of holding space for solidarity with bigger issues art can take part in.

Siyempre, we want to earn money naman. But I think that when money becomes more important, then that displaces the process of art-making to a secondary space. We want to make sure that our writers and artists don’t have to think too much about the money-making side and that’s not just about making sure we give them their fair share, but more importantly, we care about how else they can earn better from the work they do.

MOT:

In a way, artist books make art and hard conversations more accessible. They’re beautifully made objects that explore different topics by combining text, images, and the material of the book itself. How did you get into artist books?

KSS:

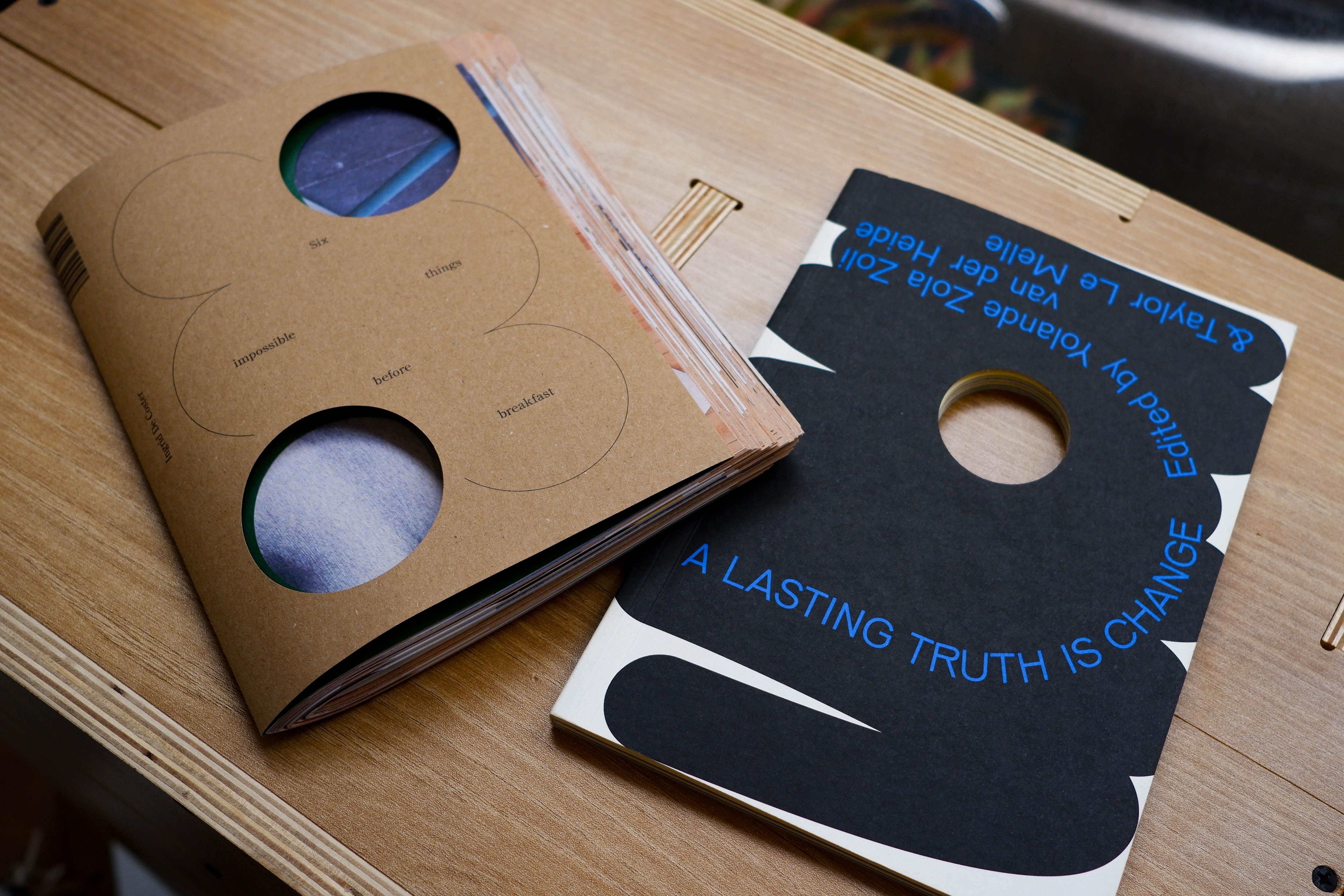

The artist book was really part of the plan from the start, when we first started Everything’s Fine. In 2022, we came out with all the books we wanted to do during the pandemic lockdowns. That was 10 books.

I have Dina Gadias’s book as a booklet., which was sold as part of an exhibit in Hiraya Gallery the early 2010s.

Lena Cobangbang’s work, we fell in love with when she gave a few copies to Koki for selling at the Manila International Book Fair last year. These were books that we thought were important to make available. When we decided to participate in the Singapore Art Book Fair, we knew we wanted to do those books plus others that were consigned with us.

We also want to introduce the artists to our reading audience, as opposed to just an audience that goes to galleries. Our approach is still about whether or not we believe in the artist, and whether or not we think that work is worth spreading to more people. It’s about generating conversations around these artifacts. When we cannot have a conversation about something, it’s not really a text worth publishing. We like that Lena’s pandemic diary is very difficult to sell.

MOT:

Is Lena’s book the one with acetate pages?

KSS:

Yes! You don’t really know what to do with it. We love that it’s the best in browsing. Anywhere we bring it, everyone look, everyone’s baffled by it. It has its own rhythm and its own life, which is what I think about books. Even when a book doesn’t move as quickly as others, we like to challenge ourselves in that sense. Where will this book sell? How do we sell this book better?

And, so far, so good. None of the books we’ve published and our republished printed matter have failed us. It attracts exactly the audience we expect. It gets the buyers that we imagine.

The basic philosophy behind curating these books is a belief in what deserves to be read by a larger audience, given the knowledge and creativity it contributes to our collective space, and in relation to that, what is worth spending money on.

MOT:

Artist books are such an investment because they require a special place in one’s home as well. Sometimes, they’re also more fragile. What advice do you have for taking care of artist books?

KSS:

The artist books we make aren’t that fragile. Even the artists themselves want these books to be read, held, and played with. They’re not supposed to be in glass cases.

That’s why the artists like publishing with us because we allow a bigger audience access to their work. We value their artist books as artifacts. You can care for the artist books by making them a part of your life. Like any good book, you’re supposed to be able to go back to them for years to come.

Oliver will disagree with me about this. He returned the original books of Dina’s and Allan’s to me in nice envelopes. I’m good with just…washing my hands. But that’s how I would handle even my favorite novel.

MOT:

One significant thread throughout our conversation is how you grew Everything’s Fine organically through intuition and taste. What advice do you have for people looking to hone their taste?

KSS:

First, be exposed to everything out there. I’m notorious for not stepping out of any performance or movie no matter how bad. It never occurred to me to start watching something by thinking “I like this” and “I don’t like this.” It’s always about giving cultural texts their independence first. Doing that for ten years across cultural production allowed me to have a sense of breadth and scope of it.

That discipline also comes from my background in cultural studies. I was a Comparative Literature major in undergrad, and my MA is in Araling Pilipino. The discipline of Cultural Studies allowed me the tendency to give works their independence and figure out what the works and artists are trying to do. I want to figure out the role the curator, or producer, or funder played, if any at all, and the dynamics between the product and how it’s sent out into the world.

Now, I’m very clear about what I like and don’t like. But, before you get there, you need to suspend judgment on what you see. It’s the only way to get exposed to the landscape, whether it’s music, visual arts, or books. I like figuring out what the works and artists are trying to do, which gives me some space for humility. In the shop, I often say “I don’t know. I need time to let that sink in before I can have an opinion.”

We’re at a point where we want to make sure that the people we support are good. We look at the product itself. Was it made well? And in fair conditions? Oliver and I ask ourselves, “Do we want to carry this book even though we know that its production engaged in unethical practices?” Often enough, we back out and don’t carry that book, especially if it’s by someone with so much power. Sa akin mahalaga yung power. You always need to ask who’s holding the power and how we can transfer some of that power to the next person.

Everything’s Fine is located at #14 Tordesillas, Unit G8, Prince Tower, Salcedo Village in Makati City. Find them on Instagram at @everythingsfineph.

Madeleine O. Teh is a designer and writer based in Manila, Philippines.