The UP CFA Studio Arts Degree Show is the culmination of students’ four years of study. As such, the titles of the works sound like those you would find embossed in silver on hard-backs in a dusty library. But this year’s show invites all to participate, even revel, in this blatant academization of art.

The show consists of 16 smaller exhibits by each artist, each with their own subject and inclinations, mediums and process. However, unlike a traditional show, there is no mystery to the works. The artists are expected to elucidate and explain their thought process and production - every step is documented, every intention articulated, every choice selected with surgical precision, ready to be picked apart by professors. Many controlling factors are present, such as material and economic limits, and the need to balance research against confusion from overanalyzing or convoluting ideas. Even the simple anxiety over getting passing grades is at play - their degrees hang in the balance. This approach to art-making might be alienating to some, but at the same time it makes the academization that is common within the institution more accessible to the audience and general public.

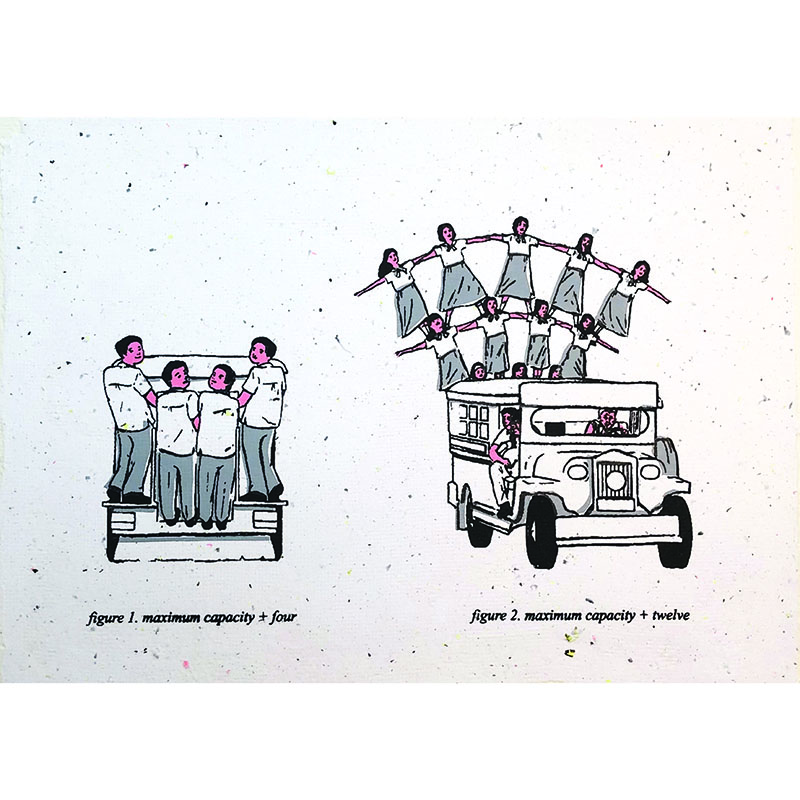

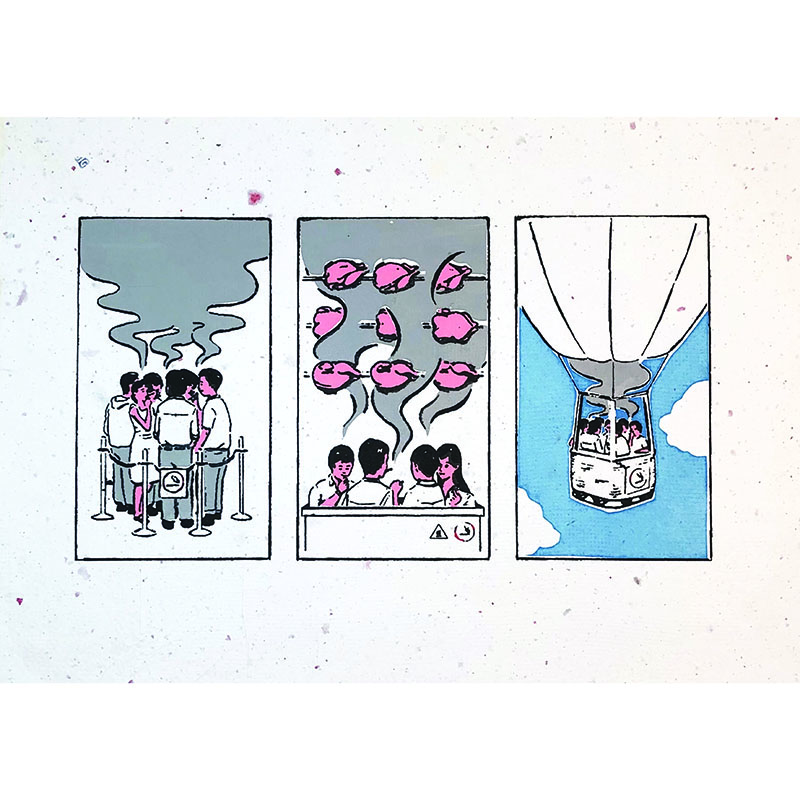

Quite close to the concerns of the general public is Marcus Aragon’s Bahala Na: A Satire of Filipino Resilience in Print. Conductors doing gymnastics on a bus, smiling young professionals packed like sardines in the MRT, pedestrians playing a game of limbo on ill-designed footbridges - each of the illustrations in Aragon’s serigraph prints are decidedly absurd but a mere step away from reality. All too familiar is the dread of the Filipino working man’s daily commute, the blank, smiling faces looking on the verge of breakdown. Civics illustrations, such as those found in American colonial textbooks, have placed the harmony of a community on the shoulders of a “model citizen”. But when resiliency is lauded as a virtue, the government responsibility of providing better infrastructure is diverted into the public’s ability to cope. The use of silkscreen printmaking embraces the method of mass-production, while the use of handmade paper out of recycled cigarette boxes injects objects from a daily commute into the actual process of the work.

Perhaps adjacent to the concerns of Bahala Na is Ava Tuñgol’s Wow, Sulit!: Painting Piecemeal Culture. Household product logos are segmented into small sachet-sized paintings in the spirit of sari-sari stores’ tingi-tingi business model. The irony is that buying piecemeal is usually more expensive than buying in bulk, but is the only amount a lot of households can afford daily. Stemming from this necessity, smaller sizes also mean more packaging, which in turn exacerbates the issue of plastic waste. This is displayed in Aleks Jugueta’s A Plastic Apocalypse, a lechon feast made entirely of plastic waste. Off-putting instead of mouthwatering, the composition utilizes common vanitas (a Dutch still life genre) symbols such as unfinished or rotting food as a reminder of inevitable death and the destruction brought about by an excess of plastic waste.

The apocalypse is more visceral in Rih Justo’s and Cholo Cardenas’s works. The images in Justo’s God is a Woman: Reinforcing the Female Ideal in Religious Art are forceful - quiet religious paintings become distorted, overcast, bloody, and dark. Female sex icons displace idols in bold fusion through xerography and collage, cut and manipulated as if striking out at the religious systems that reinforce the patriarchy. Dictations on gender are also central in Cardenas’s The Allegory of the Gynandromorph Butterflies: A Narrative Painting Series Portraying the Gender of Becoming. Gynandromorphs - those that contain both male and female sex chromosomes - exist in nature, and here populate the whole Eden. The images are at first glance softer - neons and pastels color the playful garden of these butterflies - until a jarring change of color. Through eight panels, the viewer is taken from blissful paradise to heartbreaking destruction. As allegory it reminds all of the role each one plays in the story - whether as an instigator of love or of war.

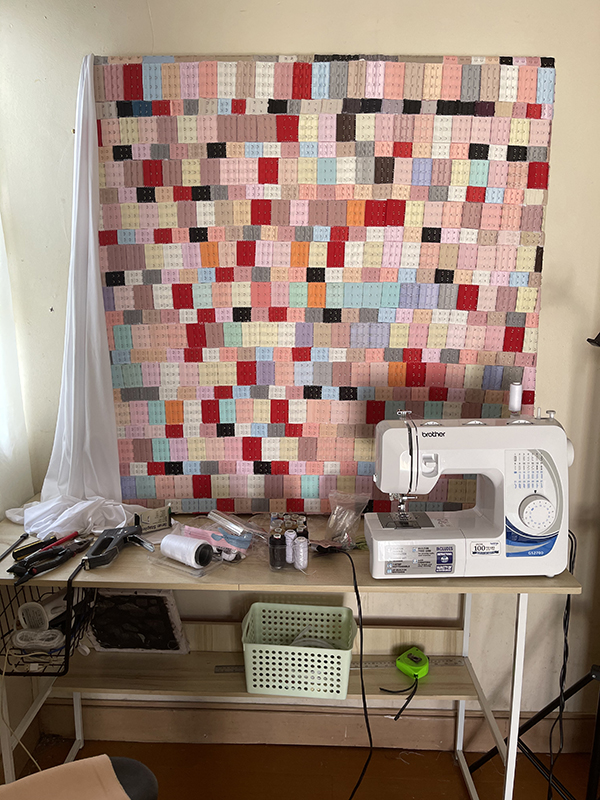

Angelou Amboy’s Worn Out: Undressing the Layers of Female Sexuality Through Intimate Apparel is a patchwork quilt of donated bra clasps. At once familiar, this small component functions as a metonym for all the women they once belonged to. Clasped together, they form a pink and pastel wall, a soft monument to the coming together of anonymous women. Francine Rivera’s Pag Tangtang: A Video Documented Performance on Teenage Motherhood and Pregnancy might be one of the stories these women could tell. The footage of the artist sewing together a pile of baby clothes is overlaid with an open, straightforward narration of the joys and hardships of motherhood as told by the artist and four other women. As the pieces of clothing are stitched in place, so do the parallels that emerge within the lives of the different women join the stories in solidarity.

Romina Sanuco’s Laya, and Lawrence Marcos’s Lagip, might function as contrasts. Sanuco’s LAYA: Stitching Memories, a Pathway to Heal is bathed in light pinks and salmons, a tapestry made of strips of T-shirt fabric needle-punched on bedsheet. At first glance sweet and girlish, the implied figure on a bed hints at a traumatic childhood experience. Remembering, through the repetitive act of stitching, perhaps is a method of confronting and reclaiming until one is released from memory’s hold. A visual opposite, Lawrence Marcos’s Lagip: Serye ng paintings ng mga lugar bilang biswal na salaysay ng pangungulila sa mahal sa buhay is dark and grim. The title, “lagip”, means “remembrance” in Ilocano, the native language of the artist’s father. Instead of setting free it grasps at and delves into a memory. As if an act of recalling, the image of a hospital is pieced together from a maze of rooms and staircases. Devoid of people, it exudes a sense of being lost and disoriented. However, the hospital is forced into the shape of a floor plan of the artist’s home - familiar rooms. Together, the two places come to the forefront of memory while remembering the departed loved one.

The title of KR Rodgers’s, Angulo: Reimagining Domestic Space Through Drawing can be read as a pun of ang gulo and anggulo, a merging of clutter and corners in one word. Panic sets in as the space seems to close in; thick, second walls of items feel like clogged arteries, constricting what is supposed to be a personal space. The drawing is surreal, but the act of putting pen to paper, perhaps like writing, attempts to reorganize and regain control, as well as articulate a need for healthy living spaces for all. In Masking Anxiety: Utilizing Compulsive Actions in Forming an Expressionist Figure, Francisco Coching IV similarly reorganizes his anxiety into new form. A figure, pensive or strained, is painstakingly sculpted out of individually rolled strips of masking tape, a harnessing of the artist’s compulsive behavior. Breaking off in parts, the sculpture looks brittle; form and process demonstrate but also salve the anxiety of the artist.

The works of Tish Meneses, Kulay Ferraris, and Reine So are more introspective - they sit with, analyze, and come to terms with the “self”, in different ways. Meneses’ The Discoidal Diorama as an Examination of my Quarter-life Crisis illustrates four stages of life in a continuous wheel, as she ruminates on her own bearings. Ferraris’s The Wallflower: Exploring Visual Metaphors with Floriography is a papier-mâché portrait painted with flowers. Each of the species, such as wallflower, makahiya, and corydalis hemidicentra (a camouflaging plant) signify the artist’s self-identity as an introvert. The layers of paper used in construction act as a protective shell. The shell is washed away to reveal the true self in Reine So’s Clarity in Isolation: A Ceramic Time-Based Process of Understanding the Self. Repetitive and slow, it presents self-knowledge as a continuous process of building a relationship with self - a project to put the time and work in; an integral step to better function beyond the self.

Finally, the works of Niccolo Inocencio and Danielle Berenguer explore the role of play in art. Inocencio’s contraption in Shifting Depths looks like a Japanese wooden puzzle. Each of the four sides are painted precisely with Op Art patterns on a four by five grid of blocks. These blocks can be pushed in or pulled out at random, allowing the optical illusions to be further distorted or amplified as they riff off of material change of depth. Danielle Berenguer’s Dream Machine: Setting Up a Playful Interactive Painting allows the participants to indirectly create a painting. Motion sensors and robotic arms translate the artist’s or participant’s movements into paint on canvas - the artist then influences but cannot control the painting. These messy dynamics of artist and environment, chance and control, echo beyond the installation.

One ought not to romanticize the Degree Show as pure play of artist in environment, nor overemphasize this as the magnum opus of a student’s career. It cannot be said definitively that this is the artists’ souls bared, or the artistic intention of their whole forward careers. It is a mere step in the expansion of their art practice. What it is is rigorous research, exploration, and testing out. It is unscathed by market agendas. Resources are poured in instead of expected out; it is a project invested in for a number of months - monetarily, physically, and emotionally expensive. These students may populate the commercial art world, in large part - some already do - with themes beyond environment, gender, women, grief, trauma, anxiety, self, and play, persisting in the knowledge that art has the capacity - and depth - to be critical and thoughtful.

The commendable UPCFA Studio Arts Degree Show is entirely online for view on wixsite.

Shireen Co is an artist, experimental cook (of leftovers), and mid-range chess nerd. Tap the button below to buy her a coffee: