Myths began as songs. Charting the topography of storytelling, Cinema’s matriarch, through time and terrain, the I, the eye, drifted from one object of curiosity to the next. Each extemporized exposition was a barter: a song for an explanation. A practice of memory for the deified, the romanticized, imparted to every traveler, every child, and the next for the brief assurance of lore.

That is to say, stories were remembered because they were sung in chorus. Now, in its grander conception, the chorus exists for as long as every spectator can identify themselves with the I, the speaker, the storyteller, the witness.

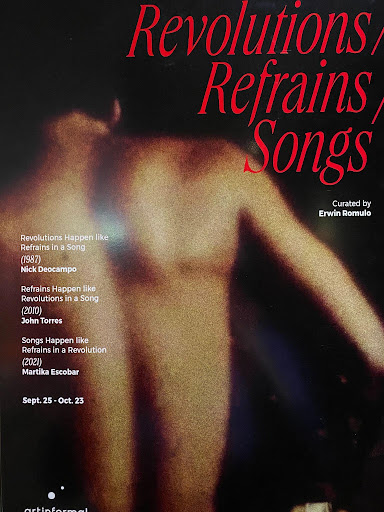

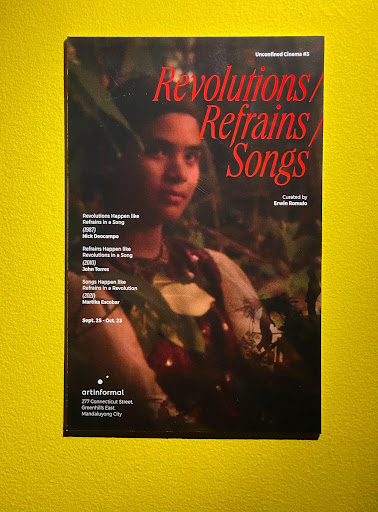

There is always an audience to convince. The I always takes its perception to the fore, imposing by way of showing. The importance of sound, song, and music (all of which are distinguishable dimensions in Film), operate as tethers to the senses that the visual nature of Cinema cannot reach. In Artinformal’s ‘Unconfined Cinema #3,’ I saw this happen in three ways. The curation’s return to myth-making lies in the peculiarity of all three films sharing the technique of improvisation bow-tied by anthems–if we can so boldly claim them so.

Cinema is its own instrument and instrumentalist in storytelling. The three films Erwin Romulo arranged reversed the process: what is usually the impetus to film is a nucleus, a core belief, that assembles the elements of filmmaking and film composition around it. With Revolutions / Refrains / Songs, the instrument itself––the camera, dictated much of the story’s trajectory. The songs and scoring, which usually act as the invisible hand that taps a vein or sets the amount of trust you, as a witness, should have for what you see, suddenly became the second narrator, front and center. The songs in each film created another dimension for an I to exist on: there is the filmmaker, the subject/object, and the song that spoke for them with clarity in a collage-like tableau.

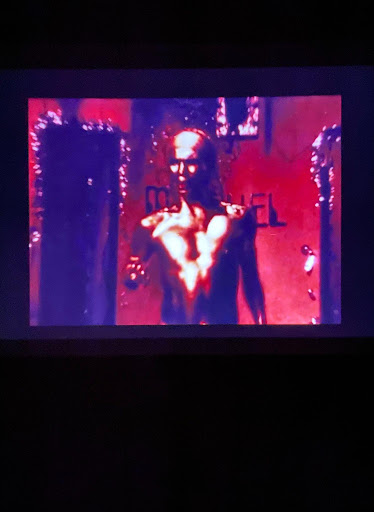

Nick Deocampo’s Revolutions Happen like Refrains in a Song (1987) was narrated in the famed director’s soft utterance. A Super 8 film camera lugged around the city of Manila and even Berlin, along EDSA as pools of people began tiding in for the revolution, cut to scenes of intimacy as Spectacle, where the I’s lover, Oliver, shifted from rope bondage to loving father, to a seemingly unbothered man on the street waiting for solicitation to a golden figure dancing to the film’s only moment where the song erupts. The narrative never gave way to fragmentation even as its conception was born from it.

Nick Deocampo recounted his childhood, his flâneury abroad when he was gaining renown as a filmmaker, his love affair with Oliver, the EDSA revolution, and the revolution that is the queer community, way before the dictator’s relevance. As the viewer, you were dragged across each encounter of the storyteller as his timbre steadied the course of the film as if you were walking with him, changing directions into smaller streets, crossing highways in the spirit of weaving a pattern (in the age of Strava, this should be familiar).

Nick Deocampo’s mythical creature wedged itself between the turbulent points of his milieu: Oliver painted golden as if untethered to the poverty and dangers that the narrator has just made to be the setting of such an extravagant scene. The irony, better yet, the melancholy in the fact that bathed this man in gold was his daily struggle to feed his son. This extravagant scene that the song marked with Oliver’s performance was part of his job description. While the idea of queerness being celebrated at that moment rattled on to the song, Oliver’s prostitution was what made him the god of that pithy scene in the first place.

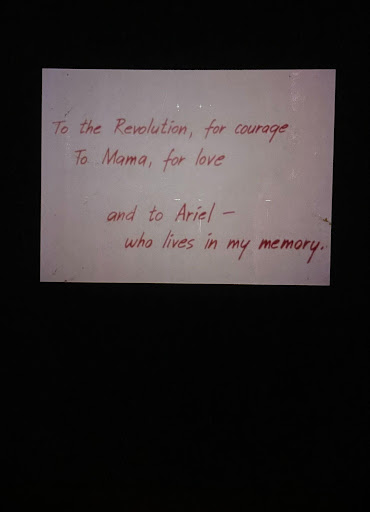

From the beginning, Oliver’s beauty drew the camera towards him. His life story rolled off the tongue of the narrator without missing a detail, and yet, every scene he occupied––even as he sat in a square to scope out clients––made his battles in an unforgiving society indiscernible, making him seem as impenetrable as his golden mythical version could be. Even as the film rolled out into its credits, Oliver was further immortalized in dedication, only this time Sir Nick addresses him as Ariel, Oliver’s real name and identity, evoking everything else that comes with the territory, perpetual in memory.

Erwin Romulo, a famed film composer, found his chorus in the three films’ reciprocity of songs. As he curated the films, commissioned the last, what was important was how each one interacted: even in their own rooms, the films spoke with each other, sang to each other even in different intervals. Its significance to him was, in this time of the pandemic, we have experienced more silence than we have ever been exposed to. The three films’ voices filled Artinformal’s gallery, reminiscent of the days when limits didn’t exist to fill a whole room with verve and voices.

John Torres’ Refrains Happen like Revolutions in a Song (2010) was what fascinated our curator to materialize this concept into the exhibition it is today. Like Sir Nick, John Torres brought his camera to Panay and Negros, lifting his eye to every interaction that his protagonist, Sarah, has with the locals. A song plays like refrains to the story, beginning with a myth of a General Guerrero, whose daughter was poisoned during an elders’ meeting. Piece by piece, this explained the end of the fight against the Americans as his grief for his daughter left him immovable. A flood in the 1900’s was said to have ended the revolution and the film finds its hook in the similar event that happened to the same place in 2008.

So much like Nick Deocampo and yet vastly divergent from him, John Torres’ improvisational filming and narration hinged on his foreignness, as opposed to Sir Nick’s familiarity. Torres did not speak Hiligaynon. He filmed Sarah and her interactions, gestures shared with the locals, and went into territories of sugarcane workers, communal bathrooms, busy restaurants, and gutters by the bustling clubs of the city without questions, but never hinting at the lack of curiosity. He filmed locals from afar, as they stood, played, roamed the marketplace selling blades.

From those fragments, he created his own story. The song that took part in narrating by setting Sarah’s story as a pursuit of a lost lover in a small provincial town, which was just flooded, came to be the central plot. What words he could not understand were captioned with his own intention of what the conversation should be about. While Sarah collects debts and wanders around asking for Emilio, her lost love, the story is knitted with the General’s and his daughter, what he mythologizes as Panay’s shared legend. Sarah never finds Emilio. While John Torres had no control over the fragments of scenes he was able to film as he roamed the town with his protagonist, he held each piece together through transliteration. One that found post-production in the same manner as mythmaking: unplanned, unconstrained, but in pursuit of finding meaning.

Martika Escobar’s Songs Happen Like Refrains in a Revolution (2021) was commissioned by Erwin Romulo himself. With complete creative autonomy, Martika decided to document life in the pandemic beginning with her singer friend, enveloping the whole film with the song, as the narrator makes herself known, turning to every mirror, every reflective surface. The song only stops when we find her speaking of the pandemic. She travels around Manila, taking videos of telephone wires, staged tea parties on a patch of grass along a sidewalk, grottos. In an effort to bring her narrative to higher ground, she shows signs of life: innumerable windows, different feet planted on different landscapes, then hellos. Faces of Martika’s friends revealing themselves through their own phones, their own cameras, waving back at themselves, but really, at us. The film ends with the singer on a hollow block chair on her balcony, singing to a setting sun. Martika Escobar had her intentions, fittingly so as we are faced with a revolution blanketed by a pandemic. The song and singer choice were just as apropos. The inclusion of many I’s through her own friends’ “eyes,” cameras, make for a quaint call for solidarity.

In its entirety, Erwin Romulo’s curation of the Unconfined Cinema #3 was a successful endeavor. Tracing back the practice of Philippine improvised film, through song no less, unlatched antiquated closures of storytelling and showed that even the most innovative, avant-garde, or rule-breaking practices in Cinema hark back to the old world practices of singing stories that always lead to the construction of myths.