‘I am that I am’, Miguel Lorenzo Uy’s ongoing solo exhibition at Underground Gallery, has an accompanying video in an atypical format. Shuffled taps on a microphone score the gallery title card as it flashes quickly in and out of frame, followed by barely audible words. As the video cuts to a wide shot of The Nameless, a ring of fire oscillates to mesmerizing effect, encircling a void pulsating at center. A text-to-speech AI then bellows the first words of the writeup: “I am that I am…,” to be followed by another that completes the sentence at a higher pitch.

As the camera slowly pulls further back to reveal more of the works, the voices are joined by countless others, all clumsy AI text-to-speech, as their syncopated voices wanly trip over one another in chorus. In their awkward inflections, the monotonous delivery wrings the biblical speech dry of sentiment, undercutting the supposed affirmations (“Your destiny is already preordained, for you are my beloved, you are My child… there is nothing impossible through Me”) to chilling effect.

What arises in me first is the discomfiture of being seen, of having the privilege of anonymity taken away. The accompanying belief here is that such anonymity never quite existed to begin with, nor was it that it had been closely guarded before. Recited in biblical tones, the show writeup addresses the viewer as an empty functionary, already bound to a covenant in which consent hardly matters. Onsite is a playback loop of gentle, unobtrusive murmurs, care of a computer program (The Serpent) that records words heard within its physical vicinity, as well as those from open-source online libraries. Recording and paring speech down into readable data then storing them in digital sheets, for one, is not a novel practice. We’re millennials; we know how personalized ads work. But when used to surface parallels between religion and technology — an endeavor ‘I am that I am’ arduously takes to task — the magnitude of technology’s influence takes on a far more pernicious tenor, and agency does not appear to measure up.

According to its description, the works in ‘I am that I am’ “follow the narrative of the merging of God, man, and technology.” In Screen — a crude photographic emulsion of TV static, a single image replicated as multiples to cover an entire wall — even noise takes on the cosmogonic value of timelessness. “A small percentage of the static,” Uy writes, “is said to come directly from the heart of the Big Bang.” More, in imagining this deity as omnipresent, it becomes figureless, abstracted: as with sonic or visual noise, it’s attuned to the description of a world shrunk, a vision of total and instantaneous connection and information superhighways where physical limitation — materiality — does not apply.

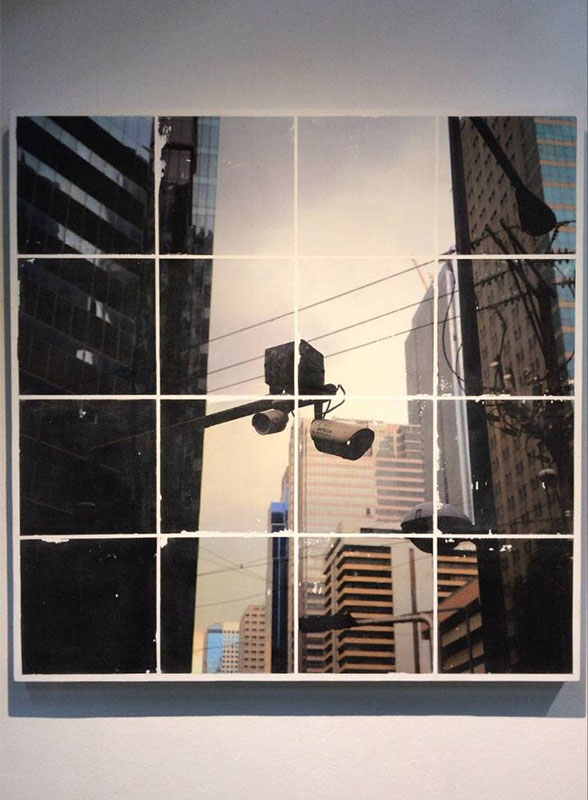

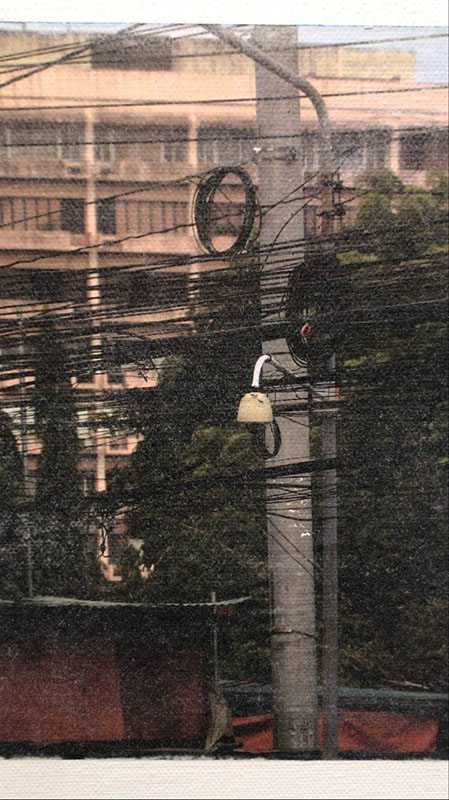

This is a thoroughly 21st-century vision of the World Wide Web, where the promise of boundless possibility can have us forget that it’s run by oligarchs with unfettered enterprises. This is also the kind of stuff from which shows so embedded in our collective consciousness, like Black Mirror, draw their material to discuss present anxieties. The earliest work in the show, Iterations, is a continuing series of photographed CCTVs, after the speculation that CAPTCHA tests are not actually meant to verify authentic users but to train AI.

What is more alarming, though, is that this merger narrative holds actual credibility. As early as 2005, Ray Kurzweil predicted that “by around 2020,” 1,000 USD would be enough to purchase a computer with the processing power equal to that of a human brain. This distinguished futurist — and, as it happens, Google’s current director of engineering — would in 2017 predict that 2029 would be when computers achieve human-level intelligence. By the year 2045, computers are predicted to surpass us, become so advanced in their thinking that they will be impossible to comprehend. This pivotal year is what Kurzweil embraces as “The Singularity.” It is the tipping point when the man-machine synthesis is considered complete, and for the supposed better: nanobots would cure illnesses; neocortices would be uploaded to a virtual cloud; physical appearances could be changed at a whim.

While Kurzweil can’t be more optimistic, resigning to the fact that this may happen in our lifetime is no argument. The resulting anxiety does not stem from a promise that life simply gets better from 2045 onward; rather, it might be that progress appears to have no other choice.

And we don’t need to look so far. For the opening sentence of his book, Terms of Service, Jacob Silverman writes, “A quarter-century after the advent of the World Wide Web, communication has become synonymous with surveillance.” It might be in that underlying suspicion that Mirage (Avatar), name alone, becomes so emblematic. The work is a single-channel video of a stationary 3D hand, palm open, with a reflective chrome surface. The source being reflected is hidden from view; we learn in the description that it’s a Google Map of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Its ambition to physically connect the world involves 140 countries to date, some of which reportedly joined against self-interest.

In an exceedingly digitized moment, a metaphor that works on the building of infrastructure, not just physical, but values, too, imagines a dystopic conversion too close to home. Because, just the same, behind a social system where people’s behaviors are engineered to like and be likeable, the sole guarantee is we forget a time before all that — and learn not to leave.

Miguel Lorenzo Uy’s I am that I am continues at Underground Gallery, Makati, until March 3. For further inquiries and bookings, start here.