Similarities, connections, interrelations are not so easily noticed in everyday life. Some subtleties between nations’ arts, histories, and cultures, however, can be. Katúlad/Kahádha establishes points of contact between modern Filipino and Arab art in Eldrick Yuji Los Baños’ first curated exhibit. Cohesive essays by Los Baños accompany works by Filipino and Arab artists, describing the contexts of their times, their implications, and where their politics, social commentary, history, and culture intersect.

While Filipino workers have migrated to Arab countries in hopes of better employment, this does not necessarily warrant a better economic status. Of an estimated 2.2 million OFWs living in the UAE, 10% of them commonly experience abuse, discrimination, and cultural stereotyping from their employers — all of whom do household work. As a Filipino raised in Dubai, Los Baños is aware of the disparities between both cultures. As curator, he sought to examine and reconcile their differences.

Eight artists from the archive, half from the Ateneo Art Gallery and the other from the Barjeel Art Foundation, have been paired for similarities in style, medium, and subject matter. The show’s concept is simple, conveying that these nations are more similar than we realize. In an Instagram exhibition, links are made clearer — works are combined in the typical triptych layout, forming a continuity between the displays.

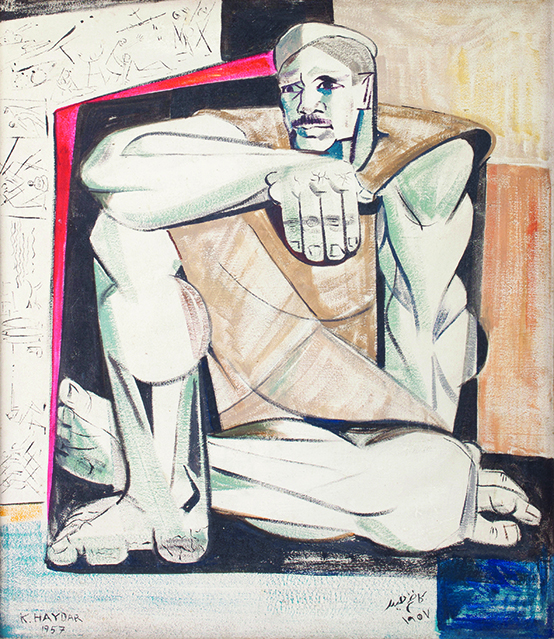

Ibrahim El-Salahi’s The Last Sound and Fernando Zobel’s Saeta No. 36 are abstract works whose styles are influenced by the artists’ transnational identities. Ang Kiukok’s Pieta, weighed against Kadhim Hayer’s Il Nous a Dit Comment Cela s’est passé (He Told Us How it Happened), depicts suffocation, a cramped space. Confined within the limits of oppression, these two artists present the political turmoil of their respective countries in constricted, cramped figures on canvas.

Further comparisons between these pieces highlight the similarity in the influences and histories that inform Filipino and Arab culture, rampant in different forms and mediums. One example would be Zeinab Abdel Hamid’s Quartier Populaire, a commentary on the state of women’s liberation in Egypt. Crammed with the hustle of a neighborhood in Cairo, women in black khimars inhabit most of the busy space. This work was painted in 1956 when women’s rights to vote were recognized; however, independent women’s movements were banned that same year. Placed beside Vicente Manansala’s Jeepneys, these works signal a turning point in their countries’ respective histories, technologies, and cultures.

What may seem like an invisible gap between these two nations is bridged by coincidences at similar points in time. These coincidences may range from color palettes, styles, subject matter, or historical contexts — whatever they may be, Katúlad/Kahàdha does well in highlighting these consistencies. In these striking parallels is a change of perspective, even biases — we can relearn and reconsider the similarities found in seemingly traceless connections. We can think to ourselves: shouldn’t two nations so alike share a better relationship?

Banner photo: NAIM ISMAIL | نعيم إسماعيل. Al Fiddaiyoun (Freedom Fighters). Oil and textile collage on canvas. 100 x 130 cm. 1969.

Image courtesy of Barjeel Art Foundation, Sharjah.

Katúlad/Kahádha is on indefinite extended view. To begin, visit the Instagram exhibition by clicking here.

Lix Sumilong likes writing, drawing, and playing with their baby nephews.